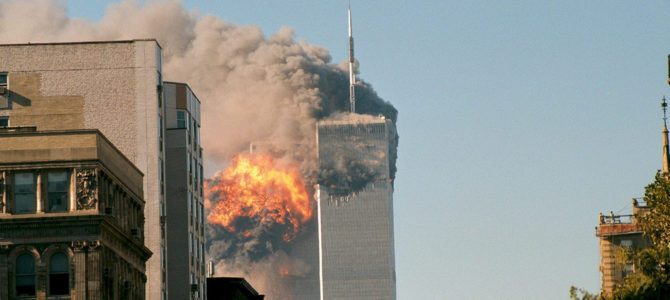

Another day, another massacre, and another string of euphemistic eulogies. Aren’t we all tired of this yet? Even in his recent speech in Riyadh, President Trump felt compelled to define terrorists primarily as nihilists, whose actions insult people of all faiths.

This is disappointing and condescending, and hearkens to the tone-deafness of the Obama era. The basic idea is that as long as you believe in anything, you can’t possibly believe in that. The truth, though, seems to be that quite a number of people do in fact believe in that.

Western secularism is derived from Christianity, and is still subconsciously influenced by Christianity in myriad ways. From this perspective, it is difficult to understand that other cultures may think positively of violence and oppression.

Most of us, for example, would affirm that the Westboro Baptist Church is monstrous and has nothing to do with the teachings of Jesus. This leads us, by analogy, to suggest that ISIS is monstrous and couldn’t have anything to do with the “real” Islamic faith. This is a fallacy born of sentimentality. But let’s start by talking about what nihilism is, so that we can see why ISIS and its ilk are not nihilistic at all.

A Brief History of Nihilism

The genesis of nihilism could be traced back to the collapse of both the Enlightenment and Romanticism. Enlightenment thinkers suggested there is an objective meaning of life that can be known through reason, whereas the Romantics suggested there is a subjective meaning of life that can be known through passion. Nihilism begins with despair over both of these projects, and confronts the possibility that life just has no meaning at all. The sense is captured by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s dark question in his novel “The Idiot”: what if the crucified Christ turned out to be nothing but a rotting corpse?

The foremost philosopher of nihilism is Friedrich Nietzsche. He distinguished between two modes of nihilism: the passive and the active. Passive nihilism is characterized by a sense of emptiness and a lack of faith in any and all values; it is a sort of depression where nothing seems worth doing. Active nihilism, on the other hand, refers to affirmatively trying to destroy existing values that are seen as arbitrary or false, so that new, perhaps truer values will be able to emerge. Nietzsche tended to think of himself as an active nihilist, and the subtitle of one of his books is, “How To Philosophize with a Hammer.”

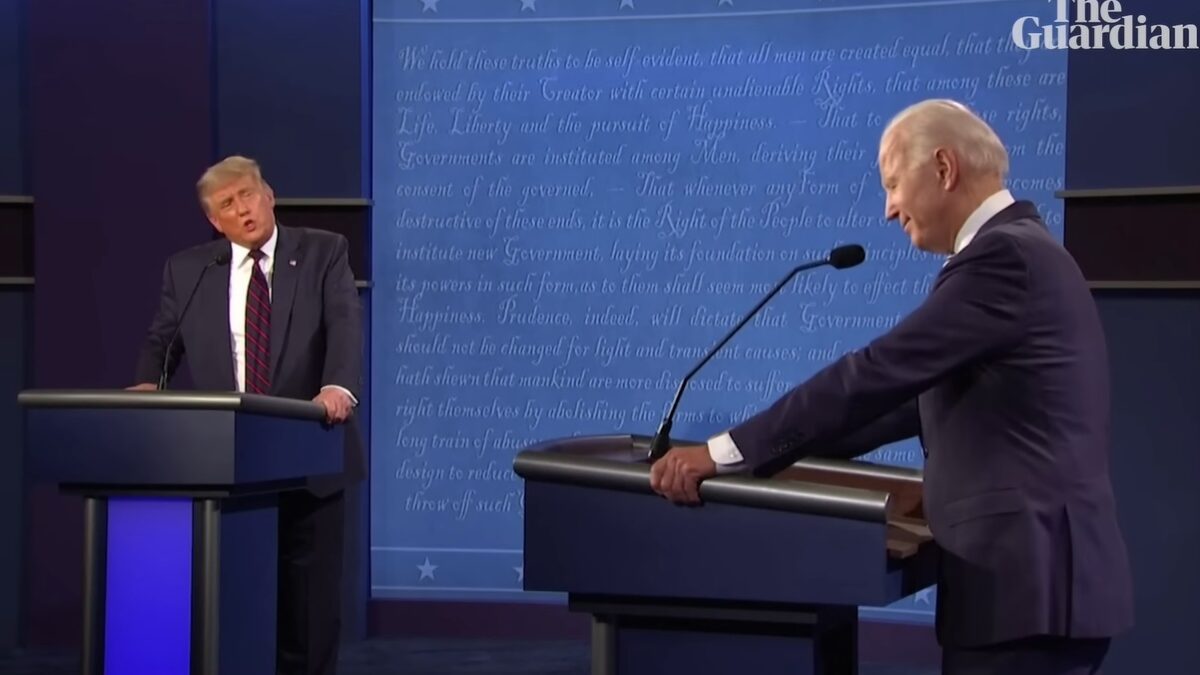

We can also speak of a nihilism of means, where the basic problem is that you will do anything to get what you want. In that sense, ISIS surely is nihilistic. But so is the current president, and much of both the Democratic and Republican parties. It is a nihilism of means to say awful things just to get a rise out of your fans at a rally, and to shut down free speech with riots, or turn into a sycophant for your own “team.” Nihilism of this kind always happens when a man sacrifices his truth at the altar of power, and it seems to be more the norm than the exception. The opposite of such nihilism is only ever personal honor.

A true nihilist of ends would be a sort of paradox. The closest example I can think of is Heath Ledger’s Joker from “The Dark Knight”: a man who wants to return all of creation back to primal chaos, for its own sake, with no further ends in mind. You could say that itself is an end, except he doesn’t care about that, either—hence the looping paradox.

Nihilism may also sometimes be a matter of perspective. ISIS looks like nihilism from the perspective of America, because ISIS is positively trying to destroy the values of America. Likewise, from a conservative perspective, progressives seem like nihilists, because they are trying to undermine the constitutional values that sustain America. But such progressives think of themselves as dwelling on the right side of History. It is thus important to avoid slapping the label of “nihilism” on an ideology just because we disagree with or fail to understand it.

Are You Sick of This Newspeak Yet?

The phrase “Islam is peace” reeks of Orwellian Newspeak. Every time I hear it, I just want to ask: “What makes you say that? Is there any foundation for it beyond wishful thinking?” It should be a commonplace among both Muslims and all other sentient people that Muhammed was not a peaceful man. Nor can the Quran be plausibly interpreted as a peaceful text.

Are we just repeating the phrase over and over again, like some demented mantra, due to the political convenience of doing so? In that case, we would be the ones engaged in a nihilism of means, sacrificing principle for sheer efficacy.

Muhammed was a military conqueror, and numerous passages in the Quran call for the literal death of unbelievers. These are objective facts. When Muhammed speaks of the sword, reason suggests that this is not the same as Jesus saying that he came to bring not peace, but a sword. Jesus is speaking of spiritual struggle; in the only passage involving Jesus and a literal sword, he told his disciple to put it away.

Some Muslims like to think this is also what Muhammed “really” meant. It’s an implausible interpretation, however, given that Muhammed spread Islam with a literal sword, and many of the surahs of the Quran are set within this context of literal conquest.

There are 13 countries in the world, all Islamic, in which apostasy (i.e., leaving Islam) is a capital offense. The subjugation of women is an integral, not peripheral, element of sharia law. We are not talking about extremists, here; we are talking about what almost everyone would agree to call mainstream Islamic nations, such as Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

Is this what peace looks like, or are these nations not “really” Islamic either? A more pressing question emerges here: is the difference between mainstream Islam and its jihadist variants really a matter of kind, or does it rather resolve itself into one of mere degree?

The Limits of Charity

It is heartening that many Muslims want to believe that Islam is a religion of peace. Good on them, obviously. But in an important sense, this evades the critical problem. Do these countless Muslims the world over also believe that Muhammed, as portrayed in the Quran and Hadith, is an exemplary man?

If Muhammed is reported to have committed violence or even atrocities, then how do peaceful Muslims square this knowledge with their own values, religious or otherwise? Are there points at which they believe it is acceptable to disagree with Muhammed, and for a Muslim to conduct his own life in a different manner, while still remaining a Muslim?

I imagine many people, including many Muslims, are sick of hearing that ISIS is not “really” Islamic. This is just plain false. Graeme Wood has put it best, in an in-depth article that should be considered required reading for anyone who wants to talk about radical Islam: “The reality is that the Islamic State is Islamic. Very Islamic. Yes, it has attracted psychopaths and adventure seekers, drawn largely from the disaffected populations of the Middle East and Europe. But the religion preached by its most ardent followers derives from coherent and even learned interpretations of Islam.”

Please note: it is not nihilism, or an absence of values; it is a positive system of values that most decent people are inclined to call evil. (Nihilism and evil are not the same thing, even if they may overlap in the popular imagination.) When the Quran repeatedly calls for devout Muslims to kill the infidels, how is it “un-Islamic” when terrorists, well, go and kill the infidels? A reasonable interpretation would be not that the terrorists believe in nothing, but rather that they believe, deeply and radically, in the affirmative commands of the Quran.

At a certain point, it is not charity but rather idiocy to ignore what these people keep affirming about themselves. As Ayaan Hirsi Ali says: “When a murderer quotes the Qur’an in justification of his crimes, we should at least discuss the possibility that he means what he says.” This would seem obvious enough, except in a culture and intellectual climate warped by Orwellian euphemism.

It should go without saying, of course, that I have nothing against the countless Muslims around the world who want to practice their faith in peace and follow an ethos of live and let live. My only question: is Islam, as an ideology, compatible with that? This is a critical reckoning in which the global community of Muslims must engage.

If ISIS is in fact justified by scripture, then what does this say about scripture, and interpretive methods related to scripture? And if ISIS is not justified, then why not? In short, there is need for a genuine reformation within Islam, marked by free critical inquiry and a refusal to turn away from the truth.