Listening to “Holy, Holy, Holy” made my grandfather cry. One day at church, after playing the old hymn with our worship team, I walked over and sat down next to him. He was about 81 at the time. Tears were streaming down his cheeks.

When he was 18 years old, my grandfather became a soldier. During World War II, he fought in the 86th infantry Blackhawk Division (341st Infantry Division, Company F). After landing in Europe, my grandfather journeyed across France before arriving in Germany. Likely in Helberhausen, from what I can guess, some friends in his company discovered a deserted mansion house. Inside were all sorts of ornate and lovely things.

The friends dressed up in fancy clothes and hats they discovered inside, stuffing pillows under their clothing and taking pompous pictures. They posed with a tiny little boy who wanted his picture taken. They put on a play, and made themselves a meal from what remained in the kitchen, then sat around together and enjoyed the quiet evening. A talented musician among them found an accordion in the house. He sat among his buddies, playing “Holy, Holy, Holy.”

The next day, Grandpa told me, nearly all those men—including the accordion player—died in battle. He would describe the moment of shock when they were attacked. They were proceeding down a quiet road, when suddenly they came under fire. I heard him tell this story many times, each time as if he’d never told it before. Each time as if he was trying to go back and wrest some sanity, logic, or control from the chaos of it.

My grandfather’s experience likely happened during the Ruhr Pocket offensive. This description seems to fit his experience:

After being held in tactical reserve at Helberhausen, the 341st was motorized und moved out at 0600. The 2nd Bn., 341st Infantry were placed in the point of the attack with the Cannon Co., 341st Inf. attached. At 1200 the general attack started with a road block near Brugge being the first objective to fall. At 1600 the force was brought to a halt by small arms and panzerfaust fire, with several vehicles being knocked out with severe casualties. The 2nd Bn. was able to regain the offense after a slight delay and continued to gain until the battalion reached Priorie (“Priorei”).

At Priorie, the 341st ran into one the well-established flak emplacements which were scattered throughout the Ruhr; such as at Bonzel and Seigen (“Siegen”). The entire 2nd Bn. was pinned down for a lengthy period and Cannon Co., 341st attempted to come to their assistance. A panzerfaust hit one personnel carrier killing four men and wounding ten others. Pfc. Rudolph A. Kovic, of Pittsburg, was a crewman on a Cannon Co. gun and his crew was subject to intense fire from a nearby house. On his own initiative he secured a bazooka and advanced to within 50 yards of the house and destroyed it, capturing 18 Germans. When Co. F. 341st Inf. was halted by the heavy opposition near Priorie. Pfc. Lynwood B. King, Jr., of Savannah, Ga., received severe flesh wounds. Nevertheless he refused medical assistance and continued to fight with the platoon until the enemy strong point was reduced.

By 1800 the enemy forces were in rout at Priorie and the 2nd Bn., 341st continued the attack and at 2400 on April 13, the Black Hawk units were drawing up on the outskirts of the huge industrial city of Hagen, where the 341st set up a perimeter defense. During the day, Generals Eisenhower, Bradley and Hodges visited the 341st Regiment CP at Attendorn.

After the ordeal the 2nd Bn., 341st had been through the previous day in advancing to the outskirts of Hagen, it was relieved at 0600 by the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 341st Inf. and the 2nd Bn. went into regimental reserve.

This skirmish may be a footnote in the history books. But for my grandfather, it changed his life. In the grand scheme of things, the loss of life was “balanced out” by overarching victory. But that 18-year-old lost nearly all his friends in one day.

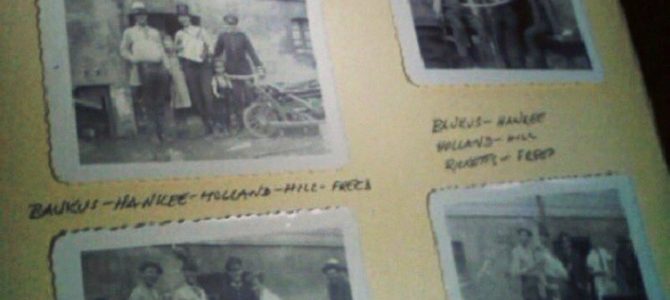

I’ve read through my grandpa’s scrapbook, and I’ve heard his stories. But sadly, as a kid, I researched my Grandpa’s experiences, or considered how his story fit into the larger themes and battles of World War II. It felt so distant: mumbled quietly in my Grandpa’s thoughtful, murmuring voice, every story took on the fuzzy feeling of a black-and-white film. The losses he experienced seemed too distant, too far off to associate with our own time.

I’m delving into the stories now. But I feel that I’m too late: I should have asked my grandfather more questions while I still could. I should have pulled out whatever resources I could find, and unearthed more facts about the battles that troubled and scarred him. I should’ve discovered the names of old war friends he remembered, and tried to track them down for him.

The burden we feel to the past should be great. Often, sadly, it is not. We listen to the murmured stories without reverence. Death is too far from us, tragedy too distant.

My generation is perhaps the most distanced from war. Our country’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are distant fact for many, their costs fully understood by few outside the military community. The 9/11 attack is the closest many millennials have gotten to the sort of shock and horror experienced by those young men—many of them just boys—in World War II.

When we think of trigger warnings these days, we often think of students on college campuses. But when I think of trigger warnings, I think of my grandfather listening to “Holy, Holy, Holy”—and of the joy that dissolved into horror in less than 24 hours. Many of us can’t even comprehend living with the pain of such memories.

When my grandfather returned home from World War II, widespread understanding of PTSD was still limited. After marriage and children, his episodes of grief were difficult for his wife and children to understand. He didn’t open up about his war experiences, or start talking about “Holy, Holy, Holy,” until my childhood years—after he’d become a Christian.

Following World War II, my grandpa went on to become a pharmacist. He made exquisitely detailed model ships in his spare time that took him years to finish. He took up watercolor painting, completing hundreds of paintings in his lifetime.

He’d wake up early and fix his grandkids eggs, bacon, and toast, or bake biscotti and chocolate chip cookies for us to enjoy after a long road trip. He helped his wife complete her crossword puzzles (in pen, pre-Google). After I got my first story published in World Magazine as a college student, he sent me a huge bouquet of flowers, with a note that said, “To the best journalist in the world.”

My grandpa made peace with his past, with the tragedy, chaos, and death it wrought. But it took decades and a transformative conversion experience to help bring that peace. Meanwhile, I enjoyed the fruit of his labor and sacrifice: the comfort and solace of safety, the sweetness of freedom and security from danger.

When my grandfather passed away last year, I sang “Holy, Holy, Holy” and “Amazing Grace” with him one last time. Although he couldn’t speak aloud, his jaw moved along to the words of the songs. We’ve been blessed beyond comprehension, to grow up with the peace we’ve had. But may we never forget that we stand on the shoulders of giants.

Today, to the soldiers who’ve fought in countless battles, who bear countless scars—I want to say thank you. Thank you for your sacrifice, for your thankless labors. Thank you for bearing up under the tragedies and the horrors of the past. You are not forgotten.