When contemplating the implications of the “Day Without A Woman,” I was reminded immediately of the Nyquil commercial in which a stay-at-home mom (or dad) asks her kid if she can take a sick day.

“Moms don’t take sick days,” the commercial told us—and it was right. We don’t usually do “A Day Without Moms.”

Some moms can play hooky, perhaps. Their husbands can take the day off, or they are able to find (and pay) babysitters. Maybe they can still send their kids to daycare, where another woman (or women) will care for their child.

But a lot of moms—especially those whose resources are slim, or who have tinier children—don’t do mom-less days. There’s too much riding on us.

What ‘Day Without A Woman’ Is Supposed To Achieve

Initially, I thought the March 8 strike was intended to protest wage inequality. But it is meant to be more than that. According to the Women’s March website,

… we join together in making March 8th A Day Without a Woman, recognizing the enormous value that women of all backgrounds add to our socio-economic system–while receiving lower wages and experiencing greater inequities, vulnerability to discrimination, sexual harassment, and job insecurity.

Over at The New Republic, Bryce Covert writes that the “Day Without A Woman” is “united by one particular reason to strike: The undervaluation of everything that women do.” (Wow. Is that all?) Covert continues:

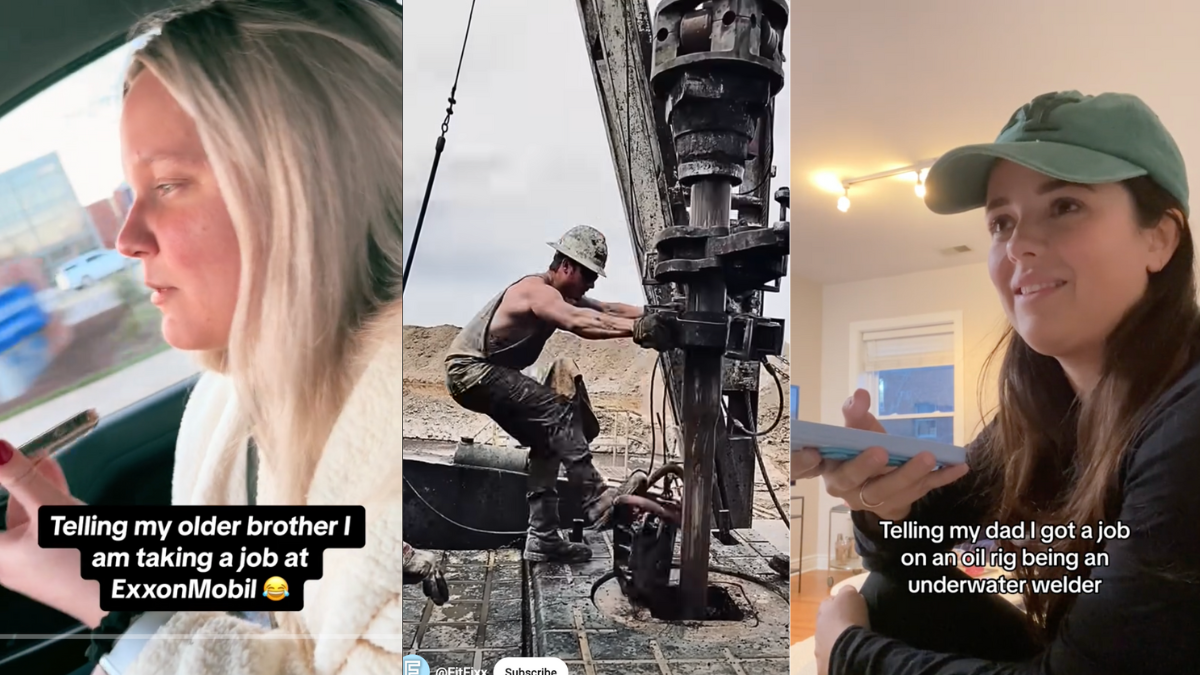

… While they’ve pushed their way into male-dominated fields like science and law, by and large women still do poorly paid, badly respected “women’s work” while men hold better remunerated jobs. The typical blue-collar job has barely improved its integration of women since the ‘70s, while progress in integrating the genders in other occupations has slowed in recent decades. Men and women largely still work in different universes, and men’s work pays better.

Women’s work also continues when they get home. On a typical day, 85 percent of women are doing some kind of unpaid labor at home, compared to about two-thirds of men, and when women do this work they spend more time on it. While heterosexual men have increased their share of the burden, most of it still falls to their female partners, even though those partners are much more likely now to be simultaneously juggling paid work.

We Should Fight Sexism and Injustice

Some things here are true, and worth reminding people about. Sexism in the workplace must stop. Women shouldn’t be mandated to wear heels. They shouldn’t be punished for birthing and raising posterity. Men shouldn’t be taken seriously while women’s concerns are discarded. Paid family leave—which includes greater paternity leave—should be a real consideration for a greater share of companies. We should empower and support single moms. And husbands should help their wives with the housework and childcare, not abandon them to do these things by themselves.

But in comparing women to men in terms of income, women discard their qualitative value in return for a merely quantitative measure of success. They shun the valuable roles that women do inhabit, seeking instead the most glamorous roles we could achieve. Additionally, they ignore much of the unseen, gritty work that many men willingly take on.

While we encourage women to become CEOs, or get STEM jobs, or achieve scientific or literary acclaim, we should also acknowledge that women often choose jobs that are more people-focused and nurturing, regardless of the pay it will entail. That isn’t meant to be a stereotype. It’s just a fact. Women choose to become nurses and daycare workers and teachers and aides. They choose to work in customer service, to become secretaries, to help the disabled or the elderly.

Income is not the sole (or even most important) measure of success and value. We should remind young women that ultimately, feminism should be about getting to do what you love, not what the world says you should do. But to get people to really believe this and embrace it, we have to change the way we think about work and work “equality.”

Think of Quality Of Life, Not Quantity of Cash

According to a 2009 report on job satisfaction, PayScale found that “Men and women are about equally likely to say that they are satisfied with their jobs; about 65 percent of both sexes say they are satisfied.” Plus, for both sexes higher job satisfaction is associated with higher job pay. But, importantly, “it typically takes a lot less money to get women to say they are satisfied with their work than it does to get men to say it.”

It could be, Catherine Rampell wrote for the New York Times, that “this difference is reflective of the men’s and women’s divergent priorities in their career choices. After all, much of the overall gap between men’s and women’s earnings can be explained by the types of careers they choose (or others might argue, the types of careers available to them). Women are more disproportionately represented in industries like health care and education, for example, that are less lucrative than some male-dominated fields but that are — as public subsidies might indicate — generally viewed as contributing to the public good.”

Indeed, PayScale’s study found that women were more likely to “say they find their jobs ‘very meaningful’ than men were, with 35 percent of women and 27 percent of men describing their jobs this way.” If you’re satisfied with your pay, and find your job meaningful, why discard those things for more money?

We Think In Terms Of Consumption, Not Creation

The most obvious answer is because our society is obsessed with money. You’re hardly useful or important unless you’re an active and constant consumer of material goods. The more you spend, the more talismans of wealth populate your life, the more our culture sees you as important.

But this mode of thinking about work only exacerbates our dissatisfaction in life. We are never content with what we have—be it our job or the state of our furniture. We always want more: a bigger paycheck, a better house, a nicer car.

Thus, it doesn’t matter if you revel in your work as a house cleaner or a cashier. If you’re making minimum wage, our culture will tell you that you don’t measure up. It wants you to be jealous of the Trumps and Hiltons and Kardashians of the world, even if you don’t want to live like them.

You can imagine how much more intense this gets when you’re not actually working. The “homemaker” or “stay-at-home mom” isn’t producing any income. Where do they measure up on the scale of important members of society?

A better, more holistic measure of happiness isn’t consumption: it’s creation. When we consider one’s work as creation, not the accrual of money for the purpose of consumption, we rank jobs differently.

Suddenly, the woman who raises her children, cooks food from scratch, and nurtures the garden in her backyard is fostering a huge surplus of goods for her family—and for society as a whole. The health care workers who earn less but foster quality of life and comfort for their clients can be seen as gifting society an enormous benefit. The daycare worker who skillfully juggles a bunch of children, teaching them about music, color, reading, and play, is growing the next generation of creators and workers.

These folks are hugely affecting society—not in dollars and cents, but in less tangible realms of creation and comfort.

Focus on Long-Term Goals, Not Just Short-Term Earnings

There’s another statistic we must keep in mind when comparing men and women’s earnings: many women work part-time. Many of them want to do this, especially if they have young children. A 2013 Pew Report found that “almost 85 percent of adults think the ability for a mom of young kids to take time off work or work reduced hours is a desirable thing.”

Indeed, two authors in the Harvard Business Review argue that “Employers can no longer pretend that treating women as ‘men in skirts’ will fix their retention problems. Like it or not, large numbers of highly qualified, committed women need to take time out. The trick is to help them maintain connections that will allow them to come back from that time without being marginalized for the rest of their careers.”

This is a highly important and encouraging point. If more companies can foster and encourage a “Mommy Track,” more women can and will choose to stay involved in their companies.

Motherhood often includes a series of compromises in order to reach long-term goals and dreams. A lot of women want to be mothers. But when you become a mom, you feel a strong connection to your children. You want to be as involved in their lives as possible. How you balance those desires with your career aspirations or financial needs will differ from situation to situation. Some women “lean in,” others “scale back,” still others “opt out.” But regardless, the desire for children must be balanced with the desire for money or work.

This needn’t be a bad thing. We just need to take a longer-term view, and envision ways to help women achieve some of their future goals, while offering them a more flexible position while their children are young. But if we measure success only by a women’s current job title (or lack thereof), and not by her future goals and plans, we are not seeing the full picture.

Think In Terms Of Money Saved, Not Just Money Earned

Anna Mussman wrote about stay-at-home motherhood for The Federalist on Tuesday, capturing brilliantly the idea that work is not just about money made and spent. It’s worth quoting at length:

The current culture delights in volume. Bigger boxes of French fries. More volunteer activities on college applications. Our values make it very easy to see the merit in those high-energy achievers whose packed schedules allow them to accomplish what seems like everything at once. It is often harder for us to admire those who delve more deeply into only one or two things. After all, their list of what they do each day seems short. To people who do not understand, their daily activities might even sound trivial.

Yet society needs deep-focus people as much as it needs multi-talented, multi-tasking people… Hard as it might be to realize, society benefits when we recognize that there are many ways of being useful members of society, of serving others, and of finding joy in our work. Stay-at-home moms are able to bring a deep focus to the lives of their children and the needs of their community. By sacrificing volume, they are able to serve others in a unique way.

I know stay-at-home moms who grind their own flour, make their own yogurt, and grow much of the food they eat from seed. That’s a powerful way to create goods and save money. These women are supporting the economy not through dollars and cents, but through long-term commitment to ecological sustainability, waste reduction, family health, and creation.

I know women who homeschooled their kids from kindergarten to graduation—kids who became military servicemen, businessmen and women, government workers, artists, graphic designers, photographers, engineers, lawyers, journalists, and authors. These women supported the economy not through a paycheck, but through nurturing dozens of little brains that now help the world through their talents.

I know women who save their families hundreds of thousands of dollars by cooking, cleaning, washing, knitting, baking, sewing, gardening, teaching, fermenting, repairing, painting, polishing, researching, driving, and caring for things entirely on their own.

It’s funny—the “Day Without A Woman” organizers encouraged women to not spend money as part of their protest. But for many highly important and unseen women out there, half their diligent labor involves not spending money, by doing things themselves instead.

Think In Terms Of Households, Not Just Individual Entities

This is controversial, especially in an age where men and women want separate bank accounts, and a prenup before the wedding day. But I think we hurt women, and society as a whole, when we divide households into income-earners and spenders, or when we measure husband and wives’ work separately.

My husband makes more than me. But we don’t call his profession “more important” than mine. While he’s bringing home the lion’s share of our income, I care for our child and our dog, make most of the food, do a lot of the housework, and crank out whatever part-time income I can. Our money goes into the same account, and is used for the same things—mortgage, food, diapers, what-have-you. But when I think of the money we make, it’s all lumped together under the Olmstead name: us. Together. Raising our child, caring for our property, feeding and clothing each other.

When we divide these earnings into him versus her, all of a sudden the household becomes a place of competition, not of support. Whoever earns more is more important. Whoever works less is the bum. We debate who’s really making the rent or mortgage payments, who should do more housework, who’s spending too much—because it’s not about advancing the health of the household. It’s about advancing the importance and legitimacy of its disparate members.

This tears households apart. It doesn’t help any of us serve or love our families. And it prevents us from using our jobs and money in the way they’re really intended: to foster human flourishing.

I’ll Stand With Women, But I Won’t Stop Working

On International Women’s Day, I want to stand with women. I want to support the disenfranchised and the voiceless, the marginalized and the oppressed. That includes women who encounter sexism in the workforce, or lack of appreciation in the home. That also includes victims of labor and sex trafficking, forced marriages, and physical abuse.

So I’ll wear red to stand with those women. I’ll avoid purchasing goods to stand with those women. That’s good for our household, anyways.

But I will keep working: because being a mom isn’t something you just stop doing. And I’m glad I don’t get to take a break.