Two months ago, as Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton was getting ready to accept her nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, protestors gathered in 95-degree weather near City Hall. Many were Bernie Sanders supporters, eventually converting to the “Green Party” gospel. One millennial gathered there told me there has never been an election like this in the nation’s history, which I was shocked to hear.

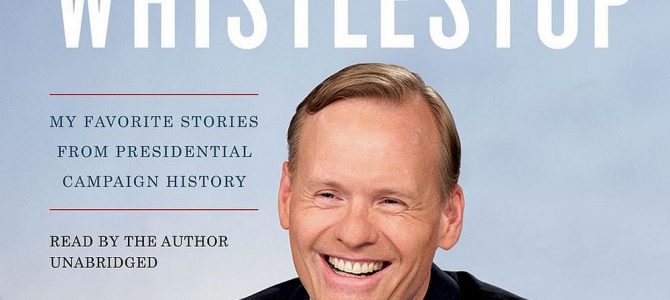

John Dickerson’s book, Whistlestop: My Favorite Stories from Presidential Campaign History, seems to disagree with the young man, reminding us of the adage in the book of Ecclesiastes, “There is nothing new under the sun.”

Maybe it’s a bit cliche to quote a text as old and well-known as Ecclesiastes, but it’s in keeping with the point of Dickerson’s book. The lessons of history help us avoid future mistakes. It also helps to know how to deal with the present when it resembles the past. In many respects, Donald Trump is not an enigma, but a composite sketch of candidates that went before him. But to millennials like me, Trump seems to stand in a class all by himself. We are the ones who would benefit from Dickerson’s book the most.

You Don’t Know Jack

Fortunately, Dickerson does not presume to judge or call us to action in the book, allowing the stories to speak for themselves, as a true reporter would.

Dickerson offers full portraits of past presidential campaigns, which stands in stark contrast to the “history-lite” that many millennials receive, taking their education from Facebook memes or videos from partisan websites designed to educate the masses on “real” history, or, the history “they” didn’t want to tell you. Dickerson isn’t dumbing things down or engaged in tiresome revisionism.

This doesn’t mean that his writing has no angle, or that he doesn’t occasionally arrange facts into a narrative. There are many times that he does so, including infusing himself into the story on occasion, as he did with this self-effacing detail about covering John McCain during the 2000 presidential election: “A dozen or so reporters encircled him, including a Time magazine correspondent who thought it was a good idea to grow sideburns that year and who hadn’t been able to get off the trail long enough to get a haircut.”

He does so again during the 1960 primary election, when John F. Kennedy was facing off against Hubert Humphrey, who later vied for the presidency again after serving as the vice president under Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1960 stars seemed to be aligning for Humphrey, a Protestant who had the most experience. Kennedy should have lost due to inexperience in Wisconsin, yet Kennedy’s Catholicism helped him win there. “Thirty-five percent of Wisconsin was Catholic—including my grandparents, which has nothing to do with this story but I thought you should know,” Dickerson writes.

But similar to the billionaire businessman who is now the presidential nominee of the Republican Party, Kennedy became the friend of the workingman. Kennedy had hustle, Dickerson wrote. He knew how to work the streets, talking to people on the campaign trail, despite Humphrey criticizing Kennedy for out-glamouring and outspending Humphrey.

Goldwater vs. Rockefeller

Some Trump comparisons also spring to mind when reading about the campaign of Arizona’s Sen. Barry Goldwater in 1964. The irony of the Goldwater election is that he was running against liberal Republican Nelson Rockefeller, a billionaire tycoon. Because of Trump’s rhetoric, which has been lobbed against minority groups (or said by media to have been so), people compare Goldwater and Trump. This is partly because Goldwater opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, although he supported all previous federal civil rights legislation and initially supported the original Senate version of the bill.

Goldwater was also the candidate of the everyday American, who wanted to diminish the size of the government and keep intact liberty for American citizens, as well as the security of the nation. But Goldwater’s victory movement was a movement of “ideas,” not material conditions (the economy), which has been Trump’s shtick from the very beginning.

Trump is much closer to Rockefeller, for those who have been paying attention. Trump is a billionaire who has proposed a higher minimum wage and regulation on free trade, while also saying in May that he would raise taxes before backing off of those comments. He is also ambiguous on topics like Israel and abortion. Anyone who suggests Trump is a representation of conservatism just hasn’t been paying attention.

Yet this time around, Goldwater isn’t whom Republican voters want, it’s Rockefeller. Trump represents the aspirations of working-class workers who desire a life like Trump’s. That’s because when Trump wins, he wins hard; and when he loses, he still somehow wins.

Strategic Ambiguity

Or you might be able to make an apt comparison between Trump and George Wallace, who made his campaign—an independent one—about the government selling out the American people. Wallace used ambiguity as his tool to present an idea and then switch hands whenever questioned about it, especially in the case of race, as in this exchange with a reporter:

Wallace: I don’t know why Negro citizens attack and assault one another –

Reporter: Are you saying it’s only Negro citizens, Governor? I mean, is that your point?

Wallace: Am I saying what?

Reporter: That it’s only Negro citizens. You keep telling me –

Wallace: I’m saying that the high crime rate [in Alabama] comes about because of the high predominance of crime among Negro citizens against each other. And that is an absolute fact. I was a judge for six years in Alabama and I know…

Reporter: Governor, aren’t you really saying that you can make safe…the streets for white people but you don’t know why you can’t make them safe for Negroes?

Wallace: I’m not saying that.

Yet, during this time, conservatives criticized Wallace “as a big spender,” Dickerson wrote, with Wallace supporting the expansion of Social Security and allowing the elderly to deduct drugs as well as other medical expenses.

Dickerson is an equal opportunity offender though, pointing out the less than flattering moments of both parties. Naturally, this necessitates discussion of Hillary Clinton, who famously stood by her husband as news broke about a twelve-year affair with Gennifer Flowers, a former nightclub performer.

The two Clintons appeared on CBS’s 60 Minutes to talk about it, which also happened to be the night of the Super Bowl. After cross-examining the pair, CBS correspondent Steve Kroft concluded his questioning and suggested that the couple were in sync because of a preordained “agreement.” It’s been that way ever since, with people looking at the Clinton family with distrust because of the ways they’ve been able to remove themselves from scrutiny. Everyone knows the rest of the story. William Clinton–always the charmer—became the next president, even though the public had been persuaded that Clinton’s tale on 60 Minutes seemed calculated. He promised them he would be there for voters, “’tilthe last dog dies.”

The book also features campaign stories in which the circumstances presidential candidates find themselves in are somewhat similar to the present election. Recent speculation surrounding Clinton’s health echoes the same speculation about McCain.

Unusual But Not Unprecedented

The press did not become a leviathan during the advent of social media, as some presume. It has always been a large factor in presidential campaigns, like when George McGovern chose Thomas Eagleton to be his vice presidential running mate, then later finding out—from an unknown source—that Eagleton had dealt with mental health issues earlier in his career.

Jack Anderson, an investigative journalist, published a story, which said that Eagleton was arrested for drunk driving, which was later debunked. Trump received a similar treatment from The New York Times when the paper published a story about how he treated women, only to have those same women come on television the next day saying the Times’ story was unfair and inaccurate.

Many thought Andrew Jackson was not fit to be president because he displayed the wrong “temperament,” including Thomas Jefferson, who told Daniel Webster, “His passions are, no doubt, cooler now; he has been much tried since I knew him, but he is a dangerous man.” How many have said that about the current Republican nominee? Just like Trump, Jackson loved the criticism, because he believed it would increase his standing with the nation as an outsider and critic of the establishment in Washington. People were growing tired of insiders having more say than they did.

These stories illustrate that although this election is unusual, it’s not unprecedented. Our political and policy priorities may evolve over time, and certainly new technology has radically changed the way the media covers elections. But Dickerson’s book is an edifying reminder that human beings don’t change. Politicians and voters alike often forget the past, and end up repeating the same mistakes.