Nothing about Sun Mu’s appearance announces “artist.” He wears Toms Shoes, has longish hair usually hidden by a fedora, and favors a T-shirt and cargo shorts as his daily uniform, typically paired with wayfarer sunglasses. During interviews he frequently puffs away on a cigarette, using it as a prop while he gathers his thoughts.

The most extraordinary thing about him is that the audience for his art mostly doesn’t know what he looks like, or what his real name is. Sun Mu still has family in North Korea, so he never shows his face in public. His real identity is a closely guarded secret. He insists hiding in plain sight is not a form of thrill-seeking. He puts himself in real danger simply because he was “destined” to become Sun Mu (a phrase meaning “no boundaries”).

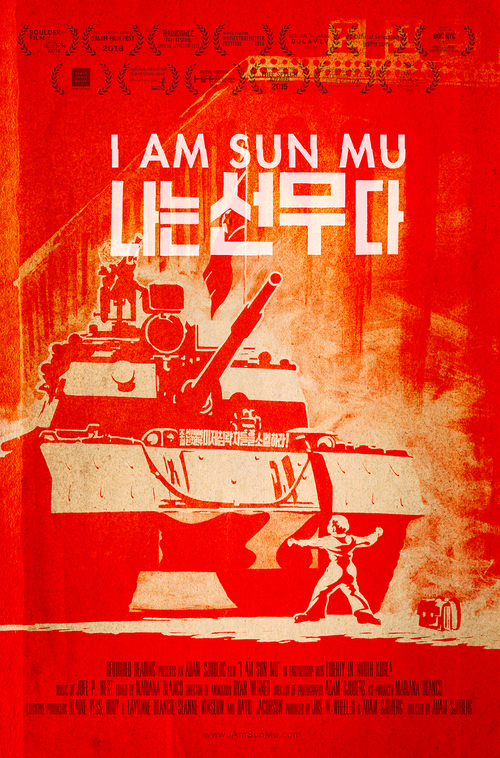

A new documentary directed by Adam Sjoberg follows this North Korean defector as he recounts his life and art under one of the world’s most oppressive regimes. “I Am Sun Mu” (2016) runs an hour and 27 minutes and centers on “Red. White. Blue,” a solo art exhibition at the Yuan Art Museum in Beijing featuring the artist’s work.

At one point during the documentary, Mu’s wife Angela jokes that she wasn’t particularly interested when she first met him. She describes his shabby appearance—socks with holes and several layers of clothing to make up for a jacket so worn it had no insulation left. But despite his threadbare appearance, he was still doing much better than many of his fellow North Koreans.

‘Why Are There So Many Lights?’

Sun Mu escaped North Korea in the late 1990s by waiting until the middle of the night and crossing the Tumen River into China. He was never politically or ideologically motivated, nor had he really planned on running away. “I thought North Korea was a great country,” Sun Mu says. “I was just hungry.” He kept a journal of his often-confused thoughts and feelings about freedom as he journeyed throughout Asia, a trip that eventually took him to South Korea (where all North Korean defectors are given full rights and citizenship).

The most surprising thing he noticed when he arrived in China was the lights. “The glittering lights,” Sun Mu says. “Plastic bags blowing in the winds. Is this rotten capitalism? Is this the rotten capitalism the North has been talking about? Why are so many lights on?” He even began to wonder if he was hallucinating. There couldn’t be that many working lights glittering all over. For at least a decade after he defected, he continued to believe the lies perpetuated by Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong Il, propaganda that said capitalism made other countries worse.

Sun Mu began his career in art long before he escaped North Korea. As a young boy, he traveled all over performing in musical skits. He was 8 or 9 when he saw Kim Il-Sung on TV with little boys and girls who sang, danced, and created art for their “Great Leader.” Sun Mu watched Kim Il-Sung affectionately pat the children on the back and immediately wanted to prove he was good enough to please the most powerful man in the nation.

Many years later, curious about his own skills, he decided to lock himself in his room one night and paint a portrait of Kim Il-Sung (drawing images of the man also known as the “eternal leader” was strictly forbidden and punishable by death). Although he was pleased he could copy the portrait accurately, he burned the work before the paint had even finished drying.

As an army recruit, Sun Mu let it be known that he was a decent artist. As a test, his superiors gave him a full day to create a poster. He thought it was a joke and finished it in mere minutes, landing him an artist position in the North Korean army. There he learned to create propaganda posters, praising North Korean leadership and denouncing “rotten” Western economics and lifestyles. Having spent so much time creating visual art that affirmed devotion to the North Korean state, it seems like a natural progression to satirical art.

Sun Mu hides his face and uses a fake name, but his art can travel the world openly. “That’s what makes art so fun,” he says early in the documentary. “Even if you work in the dark, it doesn’t stay in the dark. It becomes public.”

The Influence of Pan-Koran Culture

Throughout the documentary, Sun Mu’s paintings come to life as transitions in the narrative or as voiceovers occur. Several paintings get special attention as the artist explains his inspirations and where he was in his life journey when he created them. A friend of Sun Mu says, “if reunification were to happen, I think it would resemble Sun Mu’s paintings.” They have a clear mix of both North and South Korean style culture as well as Western influence. Sun Mu has been described as “South Korean by appearance, North Korean by heart.”

While most of his pieces are oil paintings, he created several sculptures or abstract 3D work to go along with the exhibit. He got his hands on some North Korean barbed wire and used it to create flowers. He is also profoundly influenced by music—one painting shows barbed wire that actually represents musical notes to what Sun Mu calls “his song.”

Despite his background in state propaganda and satirical art, Sun Mu doesn’t consider himself particularly political. “People make it all politicized whenever there is any image of North Korea,” he complains. “But that’s my life story.” His assistant, Ho Bin, calls the work “political pop art.” Yet his the art doesn’t fit neatly into any genre. “I just do this, or I do that, whatever I feel like doing,” Sun Mu says. Someone asks him who influences his work. He pauses and states that no one influences him, until he laughs and adds: “Oh wait. Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong Il.”

‘He Didn’t Just Paint the Suffering’

Liang Kegang, who works at the Yuan Art Museum and brought about the Sun Mu exhibit, was in Beijing on June 5, 1989, and remembers the horror of the Tiananmen Square protests. During his interview in the documentary, he’s clearly uncomfortable talking about that scene. Eventually, after a long pause he says he heard that students had died, but had no idea how many since “history has been wiped out in China.”

Like Sun Mu, he has to fear his government. He says it’s dangerous to be an artist in China under strict government supervision. In contrast to Sun Mu’s creative work, most of the North Korean art he’s seen amounts to official propaganda pieces commissioned by the government to be exhibited in Beijing. He sees a strong similarity between this art and the Chinese propaganda created during the Cultural Revolution. When he saw one of Sun Mu’s paintings he was desperate to give him a solo show at the Yuan Art Museum in 2014. “He didn’t just paint the suffering and present only the wounds,” he says. “He painted hope, a beautiful thing. This is very precious.”

For North Korean and Chinese artists, there’s more at stake than being panned by critics. Sun Mu tells interviewers he doesn’t intentionally put himself in danger, but “I’m just doing what I have to do.” Laing, the Chinese museum curator, says Sun Mu confided to him that if authorities capture him he plans to take his own life to protect his family. At exhibitions, Sun Mu talks about showing up as a tourist or pretending to be a security guard. “It’s sad that I can’t stand there in public and say, ‘I am Sun Mu.’ Because that’s who I am,” he laments.

The documentary gives voice to countless North Koreans who are now refugees or are still trapped in their hellish nation. It fittingly ends at Yeon Mi Jeong, a South Korean lookout over the border to North Korea. Sun Mu gazes back at his former home. He knows exactly what he’d do if he ever went back there: “I’d load my car with a pig, rice, and booze and I’d throw a big party in my hometown so we could all eat ‘til our stomachs burst, for once.” He hopes to one day exhibit in Pyongyang.