We often act as if media bias is some modern development of our supposedly hyperpartisan world, but it has been the norm throughout human history. What is most different about modern media bias is that the media tries to hide it under a veneer of objectivity. It has been more common for reporters to disclose their political affiliations, either outright through long relationships with readers or early on in their writings, or implicitly by working for a newspaper that openly espoused a particular political view.

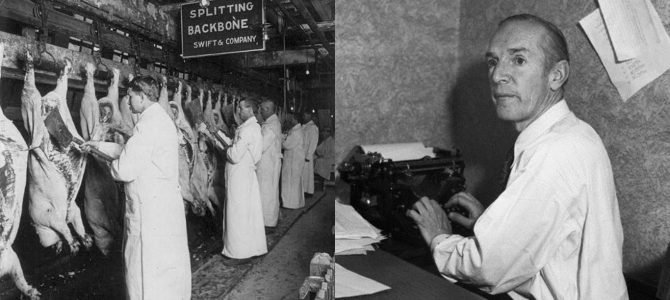

Today is the birth anniversary of the famed Upton Sinclair, who in the early twentieth century paved the way for much of today’s breathless political reporting from a progressive vantage point. Let’s give an example.

The road to Abu Ghraib began, in some ways, in 2002 at Guantánamo Bay. It was there that the Bush administration began building up a worldwide military detention system, deliberately located on bases outside American soil and sheltered from public visibility and judicial review. The administration shunned the scrutiny of independent rights monitors like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. It presumed that suspected agents of terrorism did not deserve normal legal protections, and it presumed that American officials could always tell a terrorist from an innocent bystander.

That was The New York Times’ editorial description, on May 7, 2004, of the terrorist detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, in Cuba. Titled “The New Iraq Crisis; The Military Archipelago,” the editorial characterized Guantanamo as the nexus of an American prison system located mostly at U.S. military bases that violated basic international norms of treating prisoners and condoned gratuitous physical and psychological brutality.

It became apparent the Times knew the reality of Guantanamo was different from its editorial description when the Obama administration took office in January 2009 and the newspaper, while continuing to call for Guantanamo to be closed, abandoned its “military archipelago” theme and largely ceased investigating what goes on there. The Bush-era opinionizing at the newspaper represented politically oriented narrative-making, something first practiced by early twentieth-century progressive writers, foremost among them Sinclair.

This Is What Muckraking Reads Like

Sinclair was born in Baltimore in 1878, and was the author of more than 100 books, including 1906’s “The Jungle,” perhaps the single greatest work of progressive-themed literature. Set in the Chicago meatpacking industry, the novel caused a nationwide tumult with its exaggerated and polarizing scenes.

Among the hyperbole is the author’s description of the biting cold workers supposedly endured in their homes. They “could feel the cold as it crept in through the cracks, reaching out for them with its icy, death-dealing fingers; and they would crouch and cower, and try to hide from it, all in vain. It would come, and it would come; a grisly thing, a spectre born in the black caverns of terror; a power primeval, cosmic, shadowing the tortures of the lost souls flung out to chaos and destruction.” So dire, according to Sinclair, was the cold that one February morning a child laborer came to work “screaming with pain. They unwrapped him, and a man began vigorously rubbing his ears; and as they were frozen stiff, it took only two or three rubs to break them short off.”

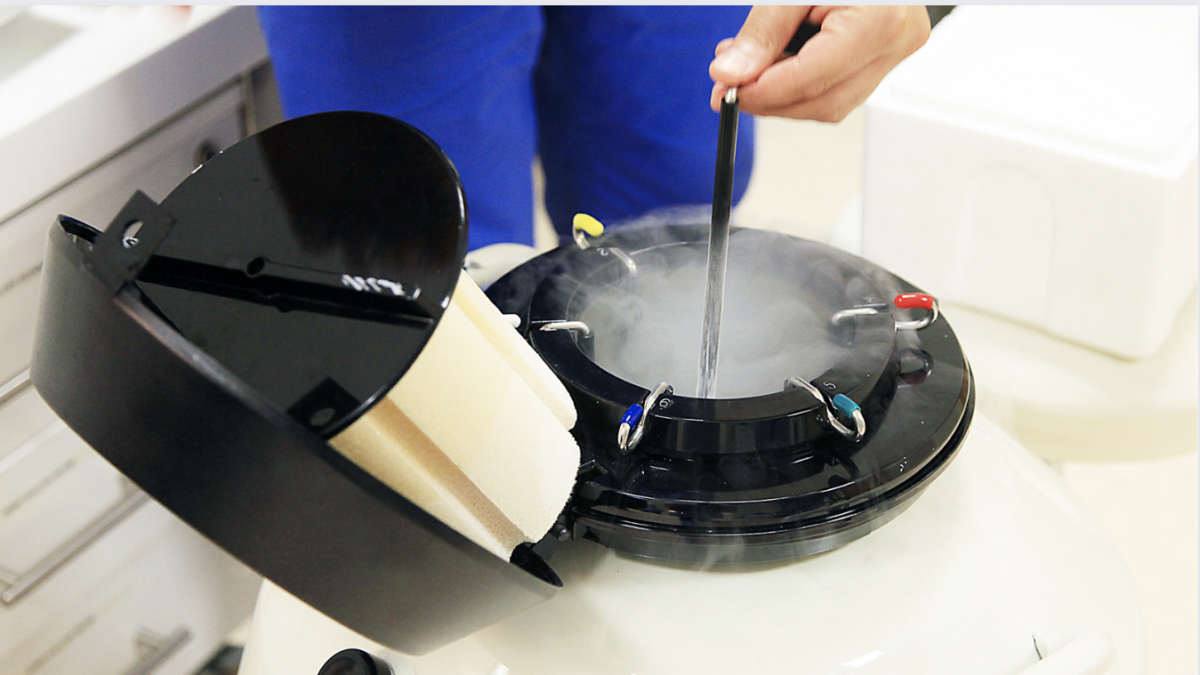

Perhaps the book’s most sensational imagery is of workers falling into vats and turning into leaf lard, or pork fat used in cooking. In some of the packing houses’ steam-filled rooms “there were open vats near the level of the floor, [and the workers’] particular trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting, – sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard!”

Sinclair’s research for “The Jungle” consisted of interviews with activists of his day. “I aimed at the public’s heart,” he would later say about the book, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

Constructing the Scenes He Paints

Contemporary successors of Sinclair include scholars who study the effects of narrative making on the mind. These scholars include University of Southern California-Berkeley cognitive scientist George Lakoff, whose 2008 book “The Political Mind” discusses the concept and practice of frame-making, and John R. Searle, also a professor at Berkeley, who wrote “The Construction of Social Reality.”

Lakoff writes of the dramatic structure of narrative making, wherein the narrative maker constructs for his audience roles like hero and villain, and the emotional structure, wherein he intends a certain emotion, such as anger and fear. Searle writes about facts as things not that have a reality in themselves, but that come into being because people agree on them, and about the place of a shared consciousness in causing that agreement.

Liberal opinion-making elites know the unreality of their narratives as they continue to construct them. But they are building the progressive future, they say, a time when we all think communally and according to what a socially conscious elite says constitutes enlightenment and knowledge. To them, it’s little concern that the narratives they construct aren’t true, because the present they build today by narrative can be rebuilt again in the same way in the future.