The Trump campaign has tried to push a few key narratives at the Republican convention. They haven’t succeeded, mind you, because they keep getting pushed off message by unforced errors, like plagiarizing bromides from Michelle Obama and treating Ted Cruz like dirt for six months, then inviting him to knife the nominee in prime time.

But the convention’s intended themes tell us the messages Trump’s people are hoping he can run on, and we can expect those themes to return during the rest of the campaign. One of the main themes is law and order. They hope to respond to the recent attacks on police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge by promoting themselves as the answer to runaway crime and a war on police.

But if the Left has constructed a false narrative about out-of-control racist cops, Republicans are constructing a false narrative about runaway crime. Rudy Giuliani summed up this narrative: “The vast majority of Americans today do not feel safe. They fear for our children, they fear for themselves, they fear for our police officers.” Then, in a riff on the Trump campaign slogan, he proclaimed, “It’s time to make America safe again.”

I understand why Giuliani would embrace this theme. There are only two reasons he has any prominence on the national political stage: he helped break the crime wave in New York City in the 1990s, and he steered the city through the terrorist attacks on 9/11. So it’s no wonder crime and terrorism are the themes he keeps returning to. When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

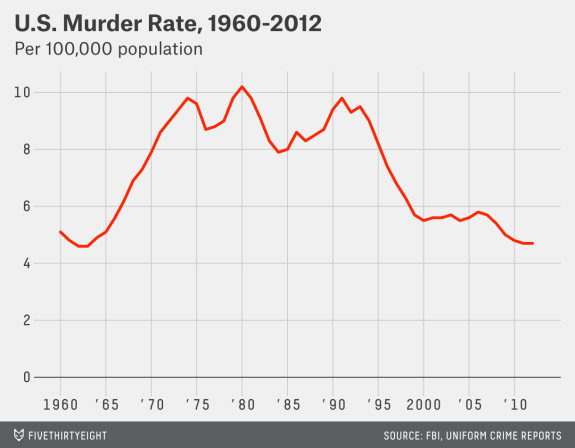

The problem is that the crime wave remains broken. I sincerely doubt that the “vast majority” of voters “do not feel safe,” and if they do, the fear is largely unjustified. Recently, I took a look at the data about police shootings that undermines the Left’s narrative about racist cops. Now let’s look at some of the data that undermines the Right’s emerging “law and order” narrative.

Take a Look at Chicago

Let’s just take one microcosm, one which, as a former resident, I know pretty well: Chicago. It has become a standard retort, when President Obama uses a mass shooting to push for gun control, to point to the most recent weekend of shootings in his home city’s high-crime neighborhoods.

Chicago certainly does have a problem with crime, policing, and shootings in some of its outlying neighborhoods. I’ve written before about how the city has been split into two tiers: prosperous upper-middle-class neighborhoods downtown, and impoverished, failing neighborhoods to the south and west.

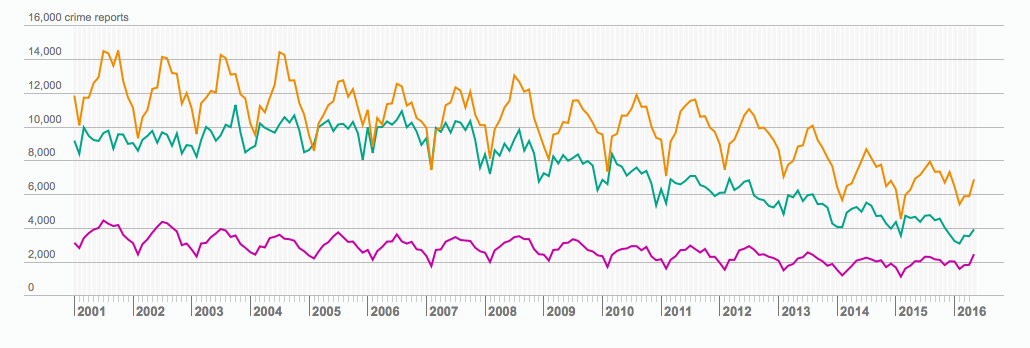

Yet even in Chicago, overall crime is continuing its long-term decline. Despite sensationalist press headline like “Chicago’s Murder Rate Soars 72% in 2016; Shootings Up More than 88%,” the Chicago Tribune‘s extensive statistics on crime show only a small seasonal uptick in violent crime. Meanwhile, here is their graph of the 15-year trend:

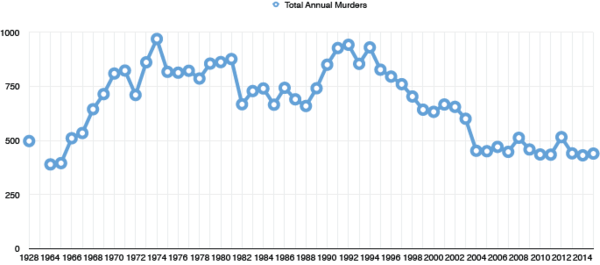

Here is an even longer-term trend for Chicago’s annual number of murders:

Yes, there was a massive crime wave that started in the 1960s and didn’t begin to subside until the 1990s. No, it is not returning, at least not yet. The data shows small ups and down within a level of killing that has been trending down to that of the pre-crime-wave era. This is in line with national-level statistics.

But what about the much-discussed “Ferguson Effect”? This narrative holds that the police shooting of a young black man in Ferguson, Missouri, a legitimate self-defense shooting distorted by the Left into the racist murder of a defenseless teenager, has been used to delegitimize the police and cause a surge in crime in big cities like Baltimore and Chicago.

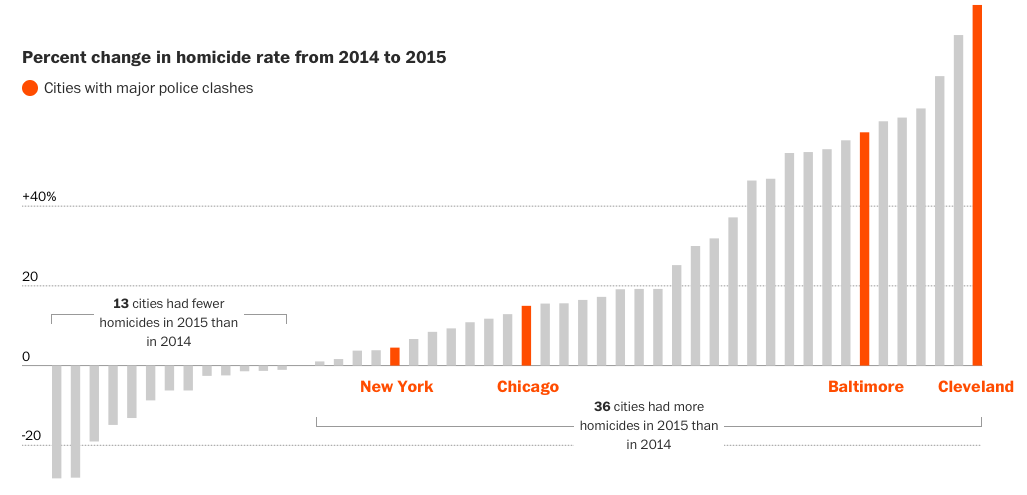

But the data is ambiguous. There has been some recent increase in violence in big cities, but it is not clearly correlated to the kind of ferment created by Ferguson-related protests or the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s summed up in this graph from the Washington Post.

Yes, there have been big upticks in Baltimore and Cleveland, presumably in response to the Freddie Gray and Tamir Rice cases, respectively, But there were also big increases in places like Nashville, Denver, Oklahoma City, and Minneapolis, while other potential hot spots, like New York City, showed only very small increases.

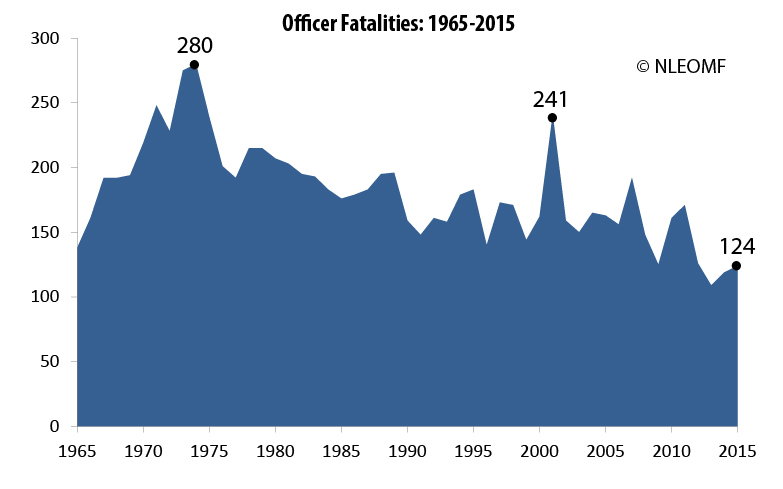

But what about Dallas and Baton Rouge? Don’t they show an increase in shootings of police officers? Yet those are just two events within a large context of long-term decline. Here is a graph of the number of police killed in the line of duty, from the National Law Enforcement Officer’s Memorial Fund.

These figures include both shootings and traffic fatalities. But so far this decade, the average number of shooting deaths of police, 53, has been outnumbered by the average number of traffic fatalities, 55. By comparison, the average number of deaths from lightning strikes is 51.

This Won’t Resonate with the Public

As someone who remembers the later years of the late-twentieth-century crime wave, when crime kept getting worse and worse and we all feared it was just going to keep increasing, I don’t think we should take the current respite from violent crime for granted. I remember when the police seemed like a “thin blue line” protecting us from anarchy, and that’s why I’m so offended by the current practice of rushing to judgment every time some activist with an axe to grind accuses a police officer of a wrongful shooting.

I certainly think there is reason to fear that recent attempts to delegitimize the police and to dismantle the law enforcement policies that broke the crime wave will lead to a resurgence of crime. But it hasn’t happened yet, and acting as if it has is a narrative just as false as the “racist cop” narrative.

More to the point, it is politically foolish. When Giuliani asserts that “the vast majority of Americans today do not feel safe,” this may resonate with a base of existing Trump supporters, which includes a lot of older voters—people my age and up, who formed their opinions on crime during the height of the crime wave—and, sad to say, a small faction of alt-right types who are eager to gin up an irrational fear of blacks and Mexicans.

But if they think this is going to resonate with the general public—if they’re hoping it will bring enough “law and order” voters to the polls to compensate for Trump’s amazing talent at repelling non-white voters—they are likely to be disappointed.

“Law and order” helped save the Republican Party once, thirty-odd years ago. It won’t save it this time.

Follow Robert on Twitter.