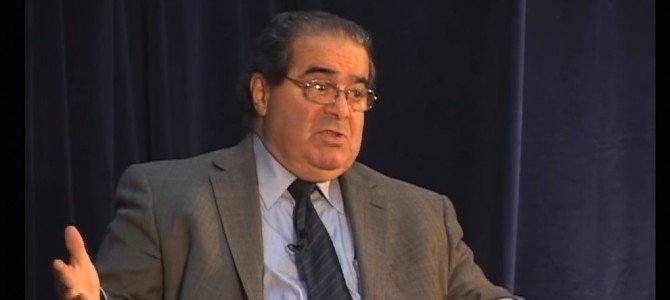

The loss of a conservative titan like Justice Antonin Scalia is such a blow to the country. Reading the rush of pieces from his admirers and colleagues has been a real joy—particularly those that have highlighted his wonderful skill as a writer, which will stand as the key to his influence.

As Joseph Bottum argues in his tribute, Scalia was “the most consequential American author of the last thirty years.” In fact, Scalia was something like the Tom Wolfe of the law. Though inclined toward law’s formalism, Scalia’s gift with the pen ranks him among our greatest writers. Like Wolfe, he flew in the face of the conventions of his time and gave us a new, although also old and, dare I say, more conservative approach to his chosen form.

For Wolfe it was recovering the realistic novel of the early twentieth century, which had fallen out of vogue with the French-inspired psychological novel. For Scalia it was recovering the legal tradition that takes seriously the text of the law and allowing what words mean to serve as the guide. Although very different forms, both have in key ways changed the arc of their profession through the sheer force of their excellent prose.

The Intellectual Confidence to Be Conservative

Maybe they’re despised by their cultural betters—indeed, Scalia was pleased to be viewed, like many great Christians before him, as “a fool for Christ’s sake”—but conservatism is not something just for fuddy-duddies who work in insurance and have never been to the opera or read a novel because of their work. It is an intellectual tradition many must contend with who are anxious to simply let progress roll.

Indeed it has been men like Wolfe, like Scalia, like Irving Kristol and William F. Buckley Jr., who have given a generation of conservatives the confidence to be a conservative. All of us have some political inclination and the conservative disposition, but even for the politically inclined, it can be hard to be a young conservative. When a college sophomore who has been raised in a world that is often hostile to principle strolls into a constitutional law class and reads Scalia, he can’t help but feel that confidence to be a conservative.

For any intellectual movement to persist, it needs such thinkers and Scalia, like Wolfe for the budding conservative-minded novelist, or Buckley, for the budding conservative polemicist, or Kristol, for the budding conservative public intellectual, produced a paper trail that will long outlive him. This paper trail was famously intentional. Scalia sought to write his opinions in a manner that might make them last. In this respect, like many others, he succeeded.

Words That Will Endure

Anyone who has ever read his famed Morrison v. Olson dissent can’t forget this rhetorical flourish: “Frequently an issue of this sort will come before the Court clad, so to speak, in sheep’s clothing: the potential of the asserted principle to effect important change in the equilibrium of power is not immediately evident, and must be discerned by a careful and perceptive analysis. But this wolf comes as a wolf.” In typical Scalia fashion, this line falls in the same paragraph as a quote from the fifty-first Federalist paper.

Madison is central to Scalia’s long-term importance, since he is in the line of thinkers willing to play their instruments at the tempo of Madison’s finely tuned constitutional metronome. For Scalia, this instrument was the law. We have had no greater modern public advocate for the principles he defended.

Sure, one can cite opinions in which Scalia’s words run counter to his stated principles, but these are few and far between. As Michael McConnell writes in his Wall Street Journal op-ed on what he thinks when a student notices an inconsistency in Scalia: “That is a compliment, because it means he has principles that can be identified and objectively applied. Many justices have no principles for interpreting the Constitution, other than to see in it their own opinions about the issues of the day.”

We’re thinking of a man who had the audacity to read “the executive power shall be vested in one president of the United States” as meaning what it so plainly means instead of going through the ridiculous rhetorical contortions of many a justice past. This justice has moved us past years of rational-basis analysis and everyone’s favorite four-part test du jour back toward rigor.

A Keeper of the Pact Between Generations

Further, is there a greater example of the virtues of conservatism than a man who dies while hunting in Texas, surrounded by a massive family? Is there a greater paragon of what is high about public life than a man who, although a real scholar, deigned to do the public’s business for 30 years on the highest court, defending a distinct American constitutionalism?

Justice Scalia’s life work embodied the Burkean notion of societies as sacred pacts between generations. We are only as good as the embodied wisdom of the ages, but someone has to pass down this wisdom. We have thinkers like Scalia to thank that this constitutional wisdom has been passed along, and with it the confidence to be a conservative for the next generation, one facing challenges we’ve been equipped to learn are not exactly new.

Believers can respect Scalia’s virtue for reasons even greater. He took to heart a central contention of the Christian faith: that God revealed himself in history and shames our strength with the foolishness of the cross.

“God assumed from the beginning that the wise of the world would view Christians as fools…and He has not been disappointed. Devout Christians are destined to be regarded as fools in modern society. We are fools for Christ’s sake. We must pray for courage to endure the scorn of the sophisticated world. If I have brought any message today, it is this: Have the courage to have your wisdom regarded as stupidity. Be fools for Christ. And have the courage to suffer the contempt of the sophisticated world,” Scalia said.

Thank God for the life of Justice Antonin Scalia. He was a fool for Christ, a brilliant jurist, and an inspiration for so many confident conservatives to come.