Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu spoke to an audience at the American Enterprise Institute last week and my colleague at The Federalist, Ben Domenech, picked up on a very interesting exchange between Netanyahu and AEI vice president Danielle Pletka. The exchange goes to the heart of what U.S. policy should be when, as Netanyahu said, we face not a choice between good and bad foreign policy options, but between good and worse.

Because I greatly admire the prime minister and mostly agree with his answer, it pains me to point out a problem with the way he invoked former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Jeanne Kirkpatrick’s most famous essay on such matters. Further, from his remarks one could infer that it is preferable to accept dictatorship as a phenomenon that can’t be avoided and to which we must accommodate ourselves.

Kirkpatrick’s 1979 Commentary essay “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” to which Netanyahu referred, is excellent. Over the years I have used this essay in my teaching. It has also been a source of insights and wisdom for my work in government. If you haven’t read it, you should, as it is timeless. In it, she offers a masterful and vigorous critique of Carter administration foreign policy.

Toppling the Wrong Dictatorships Makes Everything Worse

Kirkpatrick takes the Carter administration to task for being hypocritical and naïve. They were hypocritical because they argued the United States must stop meddling in the affairs of other countries, yet Carter’s team eagerly interfered in the affairs of right-wing dictatorships, in several cases aiding in their toppling and watching them be replaced by much worse dictatorships allied with Moscow and other enemies with far larger goals than simply controlling their own countries. She had in mind specifically Nicaragua and Iran, but also the Palestinian Liberation Organization and South Africa’s African National Congress when it was in thrall to the communists.

The Carter administration’s purported rationale was that they were concerned about human rights violations and were working to end the offending regime’s practices. But strangely their concerns were only about right-wing regimes, many allied with the United States.

Here is where the naiveté comes in. Enemies of the United States, like the Iranian mullahs who took over after the shah was toppled and the communist Sandinistas who established their dictatorship over Nicaragua, built even worse regimes that violated human rights far more than those they replaced. Communists and jihadists care nothing for our human rights concerns; in fact, they violate those rights as a matter of course.

But much worse is that the newly installed regimes represented direct threats to the United States and its interests at home and abroad. The Iranian mullahs weren’t only concerned about controlling Iran; their goal was Shia Islam’s dominance over the entire Middle East, the destruction of Israel, and the United States relegated to its own hemisphere.

The communist Sandinistas who took over Nicaragua were not just focused on controlling that tiny Central American country. Like Cuba, they worked in league with the Soviet Union to spread a Moscow-led communist revolution throughout Latin America. Carter’s policy not only helped bring greater harm to the peoples of many countries; it actually aided the greatest and most dangerous enemies of the United States.

Thus Far with Kirkpatrick, So Good

Netanyahu’s reference to Kirkpatrick in his AEI remarks was understandable. Pletka had asked him if it was better to rely on dictators in the Middle East to keep a lid on the Islamist radical threat rather than overthrowing them and having to deal with the threat ourselves.

Netanyahu seemed to agree, and used Kirkpatrick for support. He simply wanted to point out her wisdom in encouraging the United States not to get so focused on the problem of Arab Islamic authoritarian regimes that we miss the larger threat: radical Islamists of both the Shia and the Sunni stripe who want to literally control the region and beyond, hitting their far-away enemies in their homelands using their control of material and territory in the Middle East.

But Netanyahu used Kirkpatrick’s essay the way many people have been using it for years, and it risks distorting her views. In her essay, Kirkpatrick said far more than what Netanyahu referred to. In addition to warning the Carter administration not to miss the forest for the trees, she makes a very important point about the various natures of non-democratic regimes.

Since many traditional autocracies permit limited contestation and participation, it is not impossible that U.S. policy could effectively encourage this process of liberalization and democratization, provided that the effort is not made when the incumbent government is fighting for its life against violent adversaries, and that proposed reforms are aimed at producing gradual change rather than perfect democracy overnight.

To accomplish this, policymakers must understand how actual democracies have actually come into being. History is a better guide than good intentions.

All Authoritarian Regimes Are Not Equal

Kirkpatrick was noting the difference between right-wing regimes allied with the United States on the one hand, and left-wing regimes allied with the Soviets as well as radical Islamic regimes wedded to Islamic revolution on the other hand. In short, she argued for a careful analysis of the nature of a given regime and whether that kind of regime not only can be an asset to the United States in a larger struggle but also whether that regime can be shaped and transformed in the interests of the United States.

Authoritarian regimes that do not try to control every aspect of the people’s lives might be open to change—and eventually we saw Kirkpatrick proved right as President Reagan’s policies helped move countries like Chile and the Philippines toward democracy while preserving their alliance with the United States.

But, she argued, totalitarian regimes like communist ones and radical Islamist ones cannot be expected to modify or transform themselves. She understood that they wanted to defeat the United States globally and could do so only by maintaining total or near-total control of their populations and national resources.

And they could not have changed if they had wanted to. In the case of communist states, their patron in Moscow propped them up and made them into its tools. In the case of radical Islamic menaces growing and metastasizing in Kirkpatrick’s time, those entities would come to be propped up by Iran and other state sponsors of terrorism. Only when the Soviet Union began to teeter and grow weak did communist regimes begin to reform, and ultimately most of them failed.

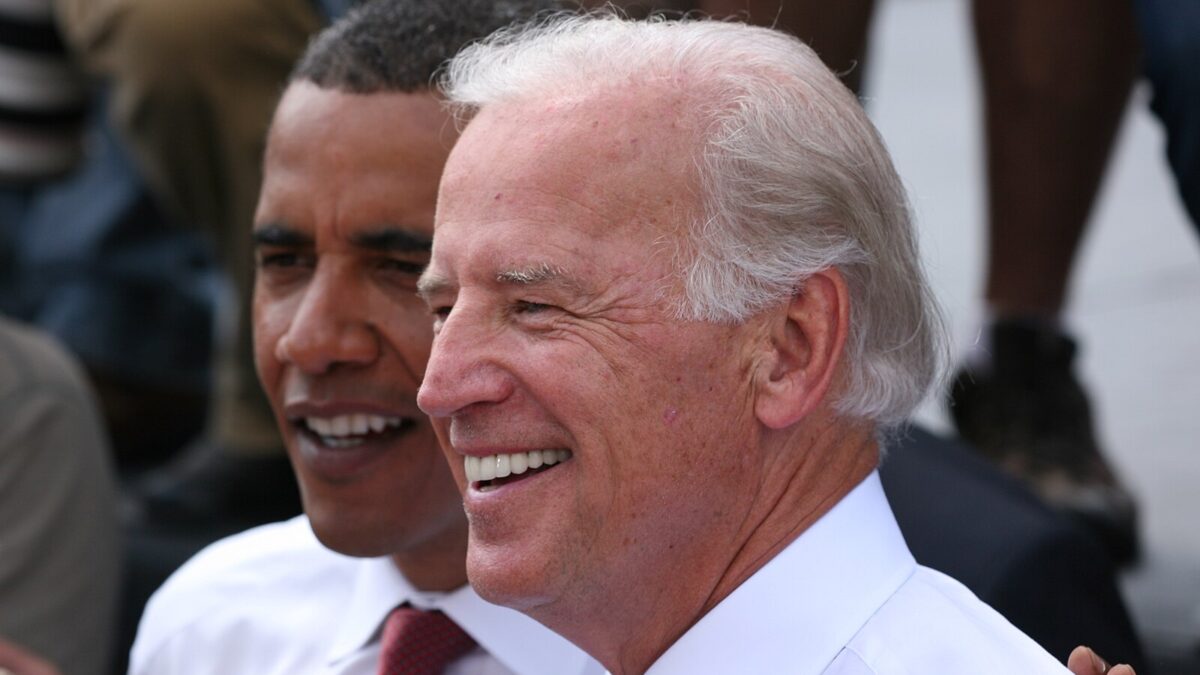

Whether Barack Obama ever comes to understand it or not, radical jihadists will never accept a world where the United States is free and strong and maintaining the international order that is required for our security.

Not All Dictators Provide Stability

So this point about the nature of regimes continues to be relevant today as we continue to face dictatorships—some that we have to work with and some that we seek to eliminate.

We don’t like working with dictatorships, so we should not resign ourselves to the idea that they are a given and nothing can be done about the nature of such regimes. I cringe when I see people use Kirkpatrick’s essay to justify positions like “we would have been better off leaving Saddam, Mubarak, and Gadhafi in place.” Let’s examine that proposition.

Newsflash: Hosni Mubarak’s regime was not stable. It fell, and hard. Nor was Gadhafi’s. (Note: I didn’t endorse our actions in Libya in large part because the administration articulated no strategy, clearly stumbled into it, and had no plan for the aftermath. But millions of Libyans rose up against him on their own volition.) I suppose one can argue that Saddam’s regime was stable in 2003, but then we don’t know what would have happened to him when the Arab Spring rolled through Bagdad. And I hardly think it makes sense to say Saddam was a source of stability in the region given that he provoked wars with his neighbors, worked tirelessly to destabilize others, and supported terrorists in the region and abroad.

My point is this: the premise that dictators are stable or that they provide stability is misguided; this is certainly true now if it was less true decades ago. Dictatorships are by their nature unstable because power in the country is always being fought over. Sometimes the revolutionary fire smolders and the regime can tamp it down. But sometimes the fire rages; just ask the Chinese, Mubarak, Ben Ali (Tunisia), Chavez and Maduro (Venezuela), and many other dictators around the world over the last two decades. These are the fires of unarmed democratic revolutionaries, not civil wars or army uprisings.

It is foolish to put too much faith in autocracies for our security, especially now that Francis Fukuyama’s thesis is proven to be at least sometimes right about the evolution to democracy. With technology making the democratic activists’ job much easier, even in a dictatorship, the people are more and more having their way, as messy as it might be.

Sometimes We Tolerate Dictatorships, Sometimes We Don’t

More than this, is it really the place of the United States to tell Egyptians, Libyans, and Iraqis (or anyone else) that they need to sit tight and hope for the best? That our security requires them to endure oppression and not make a fuss, for our sakes?

In conversations with people who have said to me “It was a mistake not to support Mubarak,” I have asked them what they propose we should have done to support Mubarak when millions of Egyptians poured into the streets calling for his ouster? Even though the Egyptian military was not prepared to shoot them down and run them out of Tahrir Square, were we supposed to somehow make the Egyptian military do it? Or should we have offered to do that for them?

This is a serious question for which I don’t get a satisfactory answer. Whether or not you like what President Obama did in Libya, I don’t see what we were supposed to do to keep Gadhafi in power other than killing a lot of Libyans ourselves.

There is a better option. Take advice from Kirkpatrick’s essay in its entirety: understand that while we have to work with dictatorships sometimes for our security, we do not have to accept that they can never change. Nowadays, we should not take for granted their stability.

Let Democracy Bloom If It Will

Since 1945 the United States has supported and encouraged democrats the world over in their struggles to be free and make their countries better partners for the United States. We have succeeded and will succeed with some. We have failed and will keep failing with others for a long time to come.

But pretending that the world is better off with so-called “stable” regimes—in 2015 with all its technology and the spread of the idea of democracy—is foolishness. It is as immoral to tell them to put away their protests as it is impractical to try to stop their uprisings.

An instructive tale of a “stable” Middle Eastern autocracy is in order. Mubarak for years claimed that we needed to support him because it was “either me or the Muslim Brotherhood.” In the Bush administration we said, “No, it is either you, or the Brotherhood, or the moderate democratic opposition that you jail, torture, kill, and exile. We choose that third group, and will support them.”

But Mubarak resisted, we didn’t push hard enough, and he won…until he lost. That is, he successfully oppressed the democratic forces until they were too few and too impotent to take up the reins when Mubarak finally fell. The Brotherhood, far more numerous and organized and supported from abroad, got their chance in an election they barely won over the remnants of the hated Mubarak regime.

Obama, like Carter, encouraged the ascendance of a worse regime, as far as the United States is concerned. Then the military got the last say, for now. It is following the Mubarak playbook and, like the Bourbons who forgot nothing and learned nothing, it is cracking down even more than Mubarak did on the democratic opposition.

Stable regime? Not a chance. Stable partner for the United States? Hardly. Get ready for history to repeat itself, because there is no longer any stability with autocracy. But by all means we should return to a policy of trying to shape the world to our needs, and that means encouraging democracy where we can.