“When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” Thus spoke Paul, author of 13 books of the Bible. A lot of us can probably relate to Paul’s words: we don’t return home from work to pull out our old Barbies or Dr. Seuss books (although some of us may still occasionally pull out the bin of Legos when we visit home).

But if you’re Meghan Daum, childish things have always been too puerile to enjoy, even from the tender age of three:

While I can’t say that I had an unhappy childhood, I was unhappy being a child. Just as there has not been a morning of my adult life when I don’t wake up and thank the gods that I am no longer a kid, there was hardly a day between the ages of three and eighteen that I didn’t yearn for the time when I would be grown-up. Aside from the usual headaches of being a kid—the restricted freedoms, the semi-citizenship—what really ailed me were the trappings of kid-dom: the mandatory hopscotch, the inane cartoons, the cutesy names ascribed to daycare centers and recreation programs, like Little Rascals Preschool and Tiny Tot Tumbling. Why was a simple burger and fries called The Lone Ranger? Why did something as basic as food have to be repackaged to resemble a toy? Even as a child I resented this lowbrow aesthetic—the alphabet-block designs on everything, the music-box soundtrack, the relentless kitsch of it all.

I can understand Daum’s distaste for certain aspects of “kid-dom”—although I have to admit, at age three, I hadn’t yet developed the perspicacity necessary to identify Barney, Toys R Us, or Disney princesses as “kitschy.”

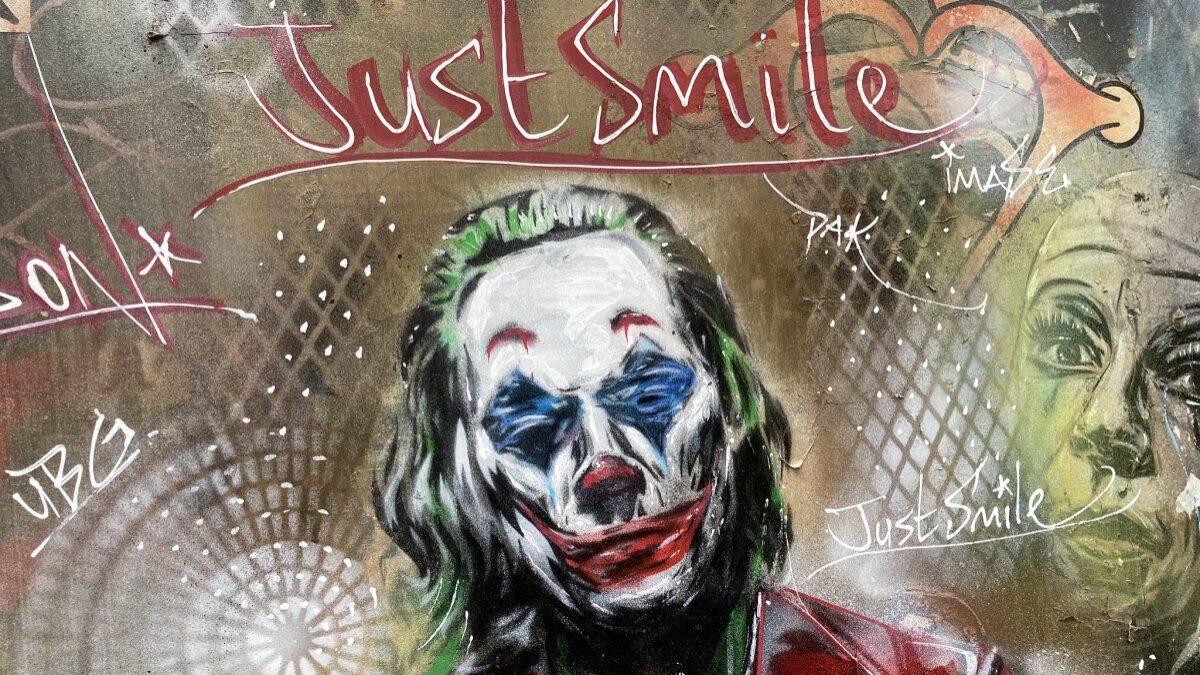

I had an instinctive distaste for some things marketed to children —Chuck E. Cheese and clowns probably being at the top of the list—and others that I slowly grew to dislike over time, as I became a bookworm (and, admittedly, a nerd). This list of things included bright, garish colors, too much pink and frills, Care Bears, Bratz dolls, baby dolls, and most kid’s television (with the exception of Liberty’s Kids and Wishbone).

But dolls—dolls remained fun. As I became a bookworm, dolls were the perfect vehicle to act out stories, imagine new worlds, live in the fairy tales I had read about or imagined. My dolls were orphaned factory workers or pickpockets in London, runaway slaves on the underground railroad, royals in disguise (a la “The Prince and the Pauper”), adventurers in Narnia, Native American warrior princesses, gypsies, investigative journalists, hobos during the Great Depression. Daum describes dolls as “the ultimate symbol of childhood; they are toy children.” But for me, dolls were just miniature humans with the potential to tell a story, fraught with dangers and adventures.

Teaching Children to Care

It’s true that a lot of my friends did just want to play house, or “mother”—they wanted to have tea parties, burp their babies, push them around in strollers (for some reason, not everyone thinks that playing orphaned factory worker is fun). But I don’t think these kids are being narcissistic: quite the opposite. These kids show the sort of nurturing, protective instinct that makes them good siblings, babysitters, or caretakers as they get older. They’re learning to think about a little human besides themselves who needs care and attention. Dolls teach them to care.

For me, dolls cultivated a similar instinct, but in a different vein. My stories often revolved around injustices and wrongs righted, stories of peril and hardship that led to happy endings. I was picking up on themes of human depravity and suffering, but also themes of forgiveness, diligence, and compassion. I was angered by injustices suffered by others, and I wanted to explore those hardships and understand them better. I was beginning to think about the difficulties of war, abandonment, poverty, displacement. Dolls helped me explore these worlds, helped cultivate in me an empathy for human experiences I had not yet encountered personally.

A Portal to Another World

Daum argues that “animals are more closely connected with the imaginative world than dolls are,” because they’re “ageless, genderless, and come in colors that defy nature. To play with a stuffed panda … is a creative act.” But it seems an unfair characterization to say creativity and imagination can only be exercised in a world untouched by age, gender, or other human designations. Perhaps it lends itself to a sort of creativity—but it’s limiting in other ways.

Playing with stuffed animals is largely a context-less sort of creativity, one in which you can’t deal with the same problems of the human condition: with history, philosophy, culture. Playing with stuffed animals is fun, but for me, it was actually less challenging and stretching.

It’s true that a lot of modern childhood feels manufactured and garish at times. There are so many bright, sparkly, talking, singing toys, it can be overwhelming. Many of them seem to hamper, rather than help, children’s sense of imagination. But dolls don’t have to be this.

I don’t know why Daum hated hers so much, why they limited her creativity in a way they never limited mine. But I do think that, for the kid who wants to grow up, who feels limited by childish things and stereotypical advertising, dolls can be a vehicle for new adventures and experiences—a way to step out of the trappings and limits of childhood, and into a whole new world.