When I got off the plane in Mumbai in June, I was alone in an unfamiliar country known for scams, and I didn’t know how to get to my hotel. So I took up the offer of an aggressive tout who was grabbing for my bag and trying to get me into his rickshaw taxi. Fifty rupees ($0.78) to get downtown.

Or so I thought. Anyone who travels to developing countries knows how stupid my decision was. The rickshaw driver took me to a slum near the airport where he and two other men demanded I go inside their “travel agency” to buy tickets. Seeing the probable robbery soon to unfold, I stood back, grabbed my bags, and hailed a yellow taxi while the three men yelled at me.

I escaped with a small loss, but others who make this mistake aren’t so lucky. Those who enter the “travel agency” have to pay extortionate fees to be allowed to go on their way.

The whole situation could have been avoided if I had just waited and taken a licensed cab to start with. Essentially, I was responsible for my mistake. But that doesn’t absolve the scammers of their attempt at robbery. This lesson—that one person’s responsibility for his own decisions doesn’t absolve the other party of blame for his sins—seems to be lost on an outrage culture more interested in slogans than solutions.

I Made Bad Choices

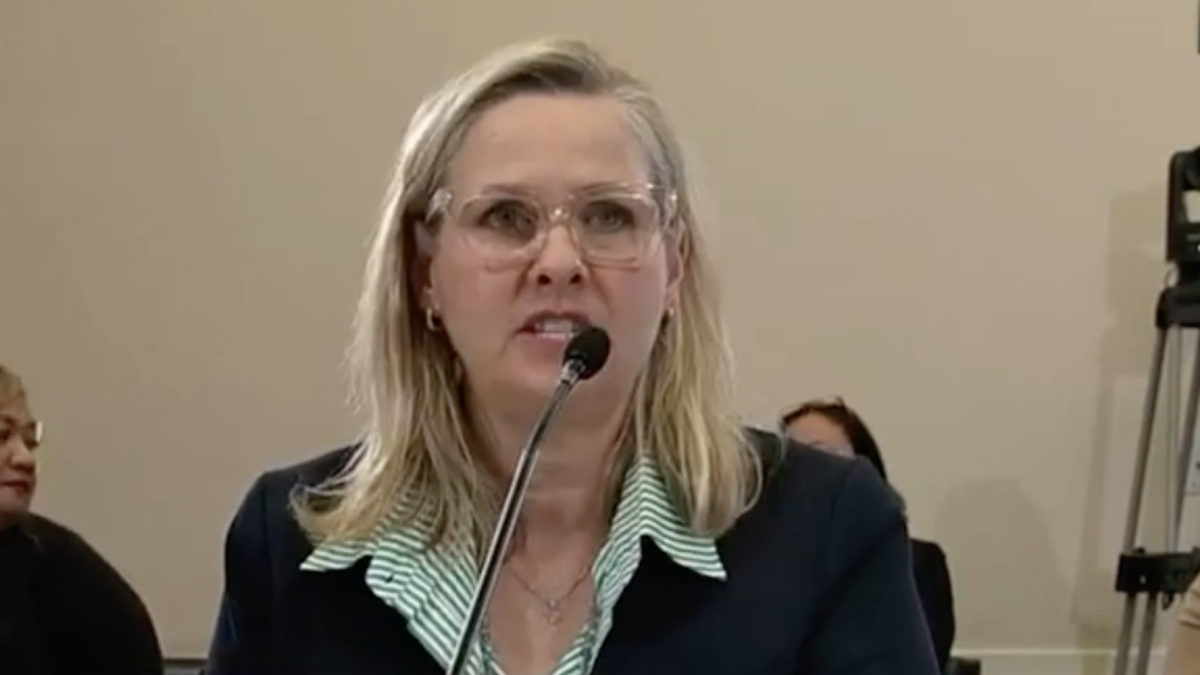

In Chrissie Hynde’s new memoir, The Pretenders singer describes an episode when she went with a bunch of strangers in a motorcycle gang and ended up getting sexually assaulted. After saying “this was all my doing” in an interview with The Sunday Times of London, the apparent rape survivor was taken to task for “blaming victims.” In a recent interview with NPR, Hynde responded to the backlash:

I’d rather say, just don’t buy the f****** book, then, if I’ve offended someone. Don’t listen to my records. Cause I’m only telling you my story, I’m not here trying to advise anyone or tell anyone what to do or tell anyone what to think, and I’m not here as a spokesperson for anyone. I’m just telling my story. So the fact that I’ve been — you know, it’s almost like a lynch mob.

If it “sounds like common sense” to you to not get high and hang out with motorcycle gangs, you aren’t alone. Hynde said so herself in the interview. “I went off with these guys of my own volition and, you know, I shouldn’t have. I mean, I was stupid to do that, but I did it,” she said.

I don’t presume to speak for Hynde’s views on the matter. She also resisted using the word “rape” in the book and interview. But from my reading, none of her comments absolve the thugs of blame. They are guilty of the crime just like Jihadi John is guilty of murdering journalists. But the point is that the attack could have been avoided if she did not put herself in the position to end up in an empty house by agreeing to go with them.

Minimizing Risks Is Common Sense

With so much attention on rape, it would be a terrible disservice not to try to decrease its occurrence. This is one particular example of a rape that could have been prevented through making better choices, and the victim isn’t afraid to say it. That doesn’t mean she wasn’t victimized. If anything, knowing what one could have done differently gives one more power to make a better decision the next time. Nor is it to say all or most assaults happen that way. But in an outrage culture, people are all too willing to strip the context of an individual event and view things in black and white.

People can and do take actions in their everyday lives to minimize risks, even in situations where we shouldn’t have to. After all, if you get hit by a driver who runs a red light, you are going to be hurt no matter whose fault it was. This is a simple fact that Salon’s Mary Elizabeth Williams probably takes to heart when she looks both ways before crossing the street. Jezebel’s Mark Shrayber should, if he doesn’t, locks the doors of his car and home. So why should we throw caution into the wind at a drunk frat party or biker bar?

Authorities rightly try to spread information about risks and try to direct others towards making the right decisions. Many universities require incoming freshmen to complete the AlcoholEdu course that warns of the risks of excessive alcohol and drug consumption, which includes becoming incapacitated to the point where you might jump off a bridge.

West Virginia University’s page about staying safe advises readers to “Stick with your friends,” and “Avoid secluded places until you know your date better.” That is essentially the advice Hynde was dispensing in her interviews.

We Tell Everyone to Reduce Risks Except for Rape

Bailey Hamblin, the feminist behind the Cunt in Converse blog, says that she avoids frat parties due to their sexist nature that encourages men to prey on vulnerable women. Another woman quoted by the Washington Post made a rule to never go upstairs at frat parties. Those would be individual solutions to a potential problems.

Elsewhere, universities and commentators are thinking about applying the same solution to all students by regulation. Ban frats, Will Ferrell said, and The Daily Dot’s Chris Osterndorf agrees, as does The Guardian’s Jessica Valenti. Rutgers University banned frat parties. The University of Missouri banned women from frat parties, but that resulted in outrage from feminists like Seventeen’s Megan Friedman, although it serves essentially the same purpose as banning frats.

As for other situations that involve high risk of assault, battery, or murder, we don’t bat an eye at suggestions that travelers should be aware of their surroundings in order to try to avoid pickpockets or muggings. The State Department has a whole website full of travel warnings about countries in the throes of violence, political upheaval, or terrorism. U.S. citizens traveling to Chad, for example, are told they “should take steps to mitigate the risk of becoming a victim of violent crime” and should “avoid travel to all border regions” where Boko Haram and al-Qaida have active presences.

Hostels around the world post signs warning of the lesser threat of scams. The American Civil Liberties Union, on its website (tip eight), advises protesters confronted by police to “stay calm” and “don’t argue, resist, or obstruct the police, even if you are innocent.” Surely they don’t think peaceful protesters are to blame for police brutality, but they wouldn’t include that advice if they didn’t think it would decrease the risk of the situation escalating and the protester getting hurt. If we didn’t warn potential victims about potential crimes and how to avoid them, we wouldn’t be protecting them, we would be putting them at risk.

Hynde is absolutely right that you shouldn’t get on a bike with a motorcycle thug, and she was right in her Washington Post interview to say you can also put yourself at risk by hitchhiking, which is why one ex-hitchhiker says she wouldn’t let her children do it. Here are a few other things people should probably not do in most situations: take a black market rickshaw outside an international airport, drink yourself to the point of passing out, and travel to a country in the midst of civil war.

But then again, Hynde’s book is titled Reckless, and she says, “[F]or all of the obvious things, I was having a good time. We all did.” If you want to live a wild life, you might take some of those actions and have some interesting stories to write. But you shouldn’t be blind to the risks.