Yesterday, Barack Obama won. The Supreme Court, in an opinion by no less a Republican than Bush appointee John Roberts, ruled that federal subsidies for health care were legal. This handed Obama a major victory—for his party, his administration, and his signature policy of six years in office.

Also yesterday, George Will posed this hypothetical, among others, to the woman who would succeed Obama in the White House. Writing to the scripted opacity that is Hillary for President Redux, he asked

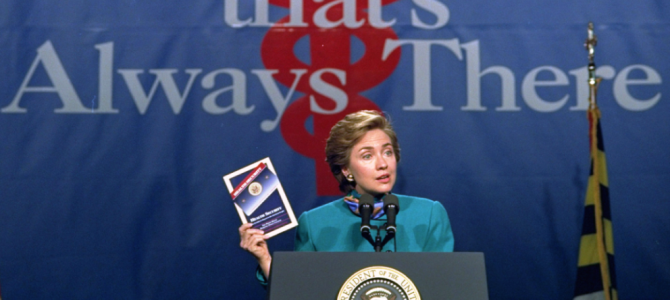

Your first leadership adventure was when your husband entrusted you with health-care reform. Using a process as complex as it was secretive, you produced a proposal so implausible that a Democratic-controlled Congress would not even vote on it. Your legislation was one reason that in 1994 Democrats lost control of the House for the first time in 40 years. What did you learn from this futility and repudiation?

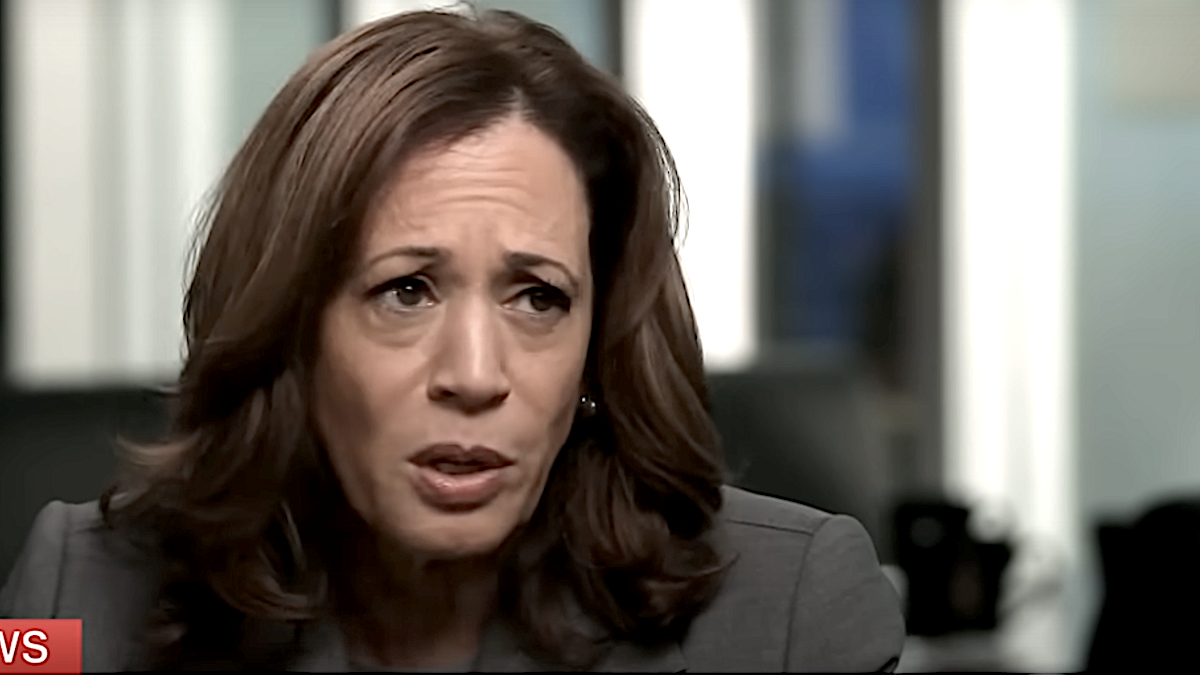

In her race for the presidency, Hillary is trying to sell us on the idea that she is a competent, seasoned leader, an aggressive and tough lawyer—maker of hard choices!—and damn the details from the right-wing conspiracy, now considerably less vast.

The Politics that Gave Us Obamacare

Like the Democrat who preceded him, Barack Obama triangulated his way into the Oval Office. Bill Clinton came right out and labeled himself a Third Way Democrat (echoing Tony Blair across the pond), splitting the difference between Democrats looking for an heir to Roosevelt and Kennedy, and centrists and Reagan Democrats looking for someone besides Bush the First, with Ross Perot siphoning enough votes out of the middle to push Bill over the top.

Obama made himself a liberal heartthrob while presenting himself as cure to America’s collective white guilt, transcending his racial heritage to appeal to Left, center, and minority voters. Lean, handsome, young, with young children and a huge smile, he was Jack Kennedy for our century, the coolest presidential candidate since, well, since Clinton played the saxophone on Arsenio Hall. Running against boring, establishment Republicans, he walked away with two races to become our second black president.

Both Clinton and Obama ran as centrists and on one thing above all: reforming health care. Clinton tried, and Obama did it. With Kennedy as his swing vote and even Roberts, now, on record on his side, the Supreme Court is behind him for good. Obama has put into place the largest and most expensive and unwieldy federal government program any Democrat ever dreamed of: the healthy among us paying for the sick, a means-tested leviathan which, like any government program, will only grow.

One Step From Power

Rahm Emanuel aside, Hillary is the thread running through these administrations. Sold as half of the “two for the price of one” 1992 campaign slogan out of Arkansas, Hillary seems to have been always with us: always there, always grasping and striving and maneuvering in the shadows to get what she wanted (those who view her as highly intelligent, loyal partner and wife to Bill Clinton should read what Gail Sheehan has to say.) She views the presidency as hers by right—or at least by tenure—and sells an image of experience, competence, and intelligence.

But there is no there there. Her public offices have been products of marriage (first lady), gift (Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s Senate seat) or Corleone-esque maneuvering to keep enemies closer (secretary of State.) Her accomplishments: lots of time on airplanes (which Will notes wryly as “peripatetic” standing in for “effective”) and lots of money raised and then diverted. Her mistakes, though, are more interesting and solid, range from gauche to criminal, and require teams of writers producing charges that glance off the feminist armor of a former Goldwater Girl.

But there is one place we can look, at Will’s urging. We can see how she performs as executive, as decision-maker. Through her mismanagement of the 1993 health-care reform effort, Hillary Clinton almost destroyed her husband and his office (who did not need her help, busy as he was trying to destroy himself and the office he held.) Bill’s congressional majorities in evaporated in November 1994, and Hillary became inadvertent kingmaker for Newt Gingrich, ushering in by her incompetence 20 more years of wildfire health-care cost growth and a rebalance of power from executive to legislative branch.

To understand how she would act in power, we must study the way she acted the last time she was in charge. Hillary has only been in charge of something once. And she blew it.

With the enormous expansion of the postwar American government, it is no longer possible to operate in what presidential historian Richard Neustadt calls “interminable chaos,” with the president as hub of a wheel around which all people and all decisions revolve. Power in the presidency must be husbanded, and when necessary devolved among competent leaders. Tough, seasoned political veterans must keep the president on track, and a lack of those people is quickly apparent.

This is why Obama, since Emanuel’s departure, has seemed in over his head. To the point: every president needs an honest broker, someone whom everyone else is afraid of, whose interest is in the president himself, protecting both man and office, telling him the truth no matter how painful. Think of Bobby Kennedy for Jack; James Baker for Reagan; Rahmbo for Obama.

HillaryCare, the Prelude to Obamacare

The U.S. health-care system is now devouring over $4 trillion per year, and presidents going back to Franklin Roosevelt have made serious efforts to reform it. When Clinton took office in January 1993, 37 million Americans were uninsured and costs were spiraling ever upward. During his 1992 campaign, Clinton had pledged to fix the problem within 100 days, and thus he (incorrectly) viewed his victory—with 43 percent of the popular vote—as a mandate for doing just that.

Five days after his inauguration, Clinton announced a task force on health-care reform, which was to be a sweeping revision of 15 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product and would finally conquer the problem that had plagued presidents since the second New Deal. Unfortunately, as Thomas Jefferson once said, “large initiatives cannot rest on slender majorities;” even less successful are poorly-planned initiatives run by the wrong people.

Although widely hailed as one of the most intelligent and politically astute presidents in American history, Clinton is to this day the kind of person who can connect intellectually (and sympathize) with two completely opposite views, convincing both sides that he is one of them. This type of president is poorly served by the “multiple advocacy” type of White House Clinton ran. General Colin Powell, George Bush’s chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who held that job through the transition to Clinton’s team, remembers the change from the brisk, decisive leadership exercised by the widely experienced and deeply seasoned George H. W. Bush to the “dorm-room bull session” style of Clinton, in which many ideas were thrown about but decisions were rare.

In setting up one of the biggest domestic reforms since World War II, Clinton needed someone who could contrast that scattershot style. He needed a Jim Baker (whom Neustadt calls “the best chief of staff in the history of the presidency”) to make the trains run on time. He needed someone with Washington experience: Leon Panetta would have been a good choice; Lloyd Bentsen; Bob Rubin; Moynihan, Clark Clifford, Gergen, somebody, anybody, a grownup who could tell him what to do.

Instead, he picked Hillary. Then, to double down on that bad bet, he chose the prickly Ira Magaziner to assist her. This was in keeping with his fatuous campaign slogan of “buy one, get one free,” playing upon Hillary’s reputation as a smart, aggressive lawyer and political whiz. Yet the choice of Hillary Clinton—in and of itself—doomed a health-care reform plan at the one moment it could have succeeded.

The Disastrous Hillary Step

The first job of an honest broker is to dispense due process, to ensure a fair hearing for all views and a good flow of information to the decision maker. The second job is to exercise quality control. Hillary Clinton did neither. In 1993, she and Magaziner created a behemoth 600-person task force that was notable for whom it excluded: congressional leaders, congressional staffers, most Republicans, interest-group representatives, and medical and insurance company experts who would not toe the “pay or play” line she advocated. This exclusion served to unite the opposition—and doom the policy.

Even President Clinton himself had only episodic involvement with the process, deferring to his wife on most decisions. The honest broker can sometimes take on such a responsibility in making crucial decisions as almost a co-president, but only if he or she is highly experienced and has impeccable judgment. Jimmy Byrnes, brought in in 1943 to run the industrial side of the war effort, played such a role for Franklin Roosevelt, as did Sherman Adams for President Eisenhower and Baker for Reagan.

These are, however, unusual cases with extraordinarily talented people. Hillary Clinton had neither the wisdom nor the Washington experience to filter information away from the president. The Clintons clung to fantasy, while Washington veterans knew the truth: it was impossible to increase benefits, insure all Americans, and still create savings in the system. You could have one of those things, but not the others.

The fair hearing necessary for good policy development, and crucial for such a mammoth undertaking as health-care reform, was missing. In a foreshadowing of the management style for which she is now known, meetings were held in secret due to Hillary’s paranoia concerning leaks. Longtime political journalists David Broder and Haynes Johnson in their book “The System” later surveyed the destruction:

No substantive interviews were permitted with the First Lady, Magaziner, or with members of the task force. They really tried to shut down the flow of information…they hurt themselves a lot. Both Clintons came to understand that the secrecy policy had been a serious misjudgment. The President said, ‘in retrospect, I think that was a mistake.’ The policy of secrecy made a bad situation infinitely worse.

A Political Disaster

Although Bill Clinton really needed a “supermajority” of between 60 and 70 votes in the Senate to create momentum to win the health-care fight, he shot for 51 votes, depending on Democratic Party unity to pull the measure through. A member of the Washington varsity, versed in Washington strategy, would have properly advised the president of the fundamental need for a coherent, well-constructed congressional strategy. Successful strategy in Congress requires coalitions, carefully constructed and nurtured. House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Pete Stark and Senate Finance Committee Chairman and policy wizard Moynihan were both opposed to the Clinton plan; success would have required listening to these key men in the early stages.

Wise Democrats knew they ignored Moynihan at their peril. In the event, Moynihan, the man whom even Will has said “has more good ideas while shaving in the morning than most people do in a career” said of Hillary’s plan, “Anyone who believes it can work in the real world isn’t living in it.”

Congressional leaders didn’t like it. Clinton’s own senior advisors—Donna Shalala, Lloyd Bentsen, Panetta, Laura D’Andrea Tyson, and Bob Rubin—didn’t like it. Poor Gergen, brought in as political cover from the Republican wings, and notwithstanding his misgivings with the plan itself, focused on strategy and advocated going “center-out:” securing moderates first, then reaching out to Republicans, then spreading outward to the ideological wing of both parties. These advisors, seasoned by extensive Washington experience, should have carried weight in the process. As it was, since Hillary Clinton and Magaziner disagreed with them, they were shut out of the planning.

So when George Mitchell gave up on the bill in the summer of 1994, no one was surprised. No Jim Baker, our Hillary. She blew it.

In Short, Hillary Can’t Govern

Rather than an honest broker, Hillary was an advocate, someone with a burning desire for one policy outcome—in this case, government-run health care—who thus excludes bad news and opposing views. Additionally, she was then as now an immensely polarizing figure, someone whom members of the opposing party viscerally loathe and whom even her own supporters acknowledge makes compromise difficult. She is exactly the type of person who should not manage policy development, particularly policy as breathtakingly complex as an overhaul of the U.S. health-care system.

One score and two years ago, we saw Hillary in charge: the only time Hillary Clinton has been put in charge of a specific, measurable policy initiative. Gergen himself described her health-care reform efforts as “a debacle in public policy rivaling the Vietnam War.” Her disastrous, secretive mismanagement of the rewrite of health care policy was a debacle of the first order, and prelude to several more disastrous, secretive debacles one might mention. Let not past be prelude.