Jacqueline Kober managed to get annulment from her marriage in New York to the man she thought she had loved when she married him in 1963. But she discovered not long after the marriage that he had been an officer in the German army and a devoted member of the Nazi Party during World War II. She found, curiously late, that he was “fanatically anti-Semitic; that he believed in, advocated, approved and even applauded Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’ to the Jewish question, namely the extermination of the Jewish people; and that he would require [Jacqueline[] to ‘weed out’ all of her Jewish friends and to cease socializing with them.”

Mrs. Kober’s complaint then was that the marriage was defective because she could not love a man who loved Hitler and his works. It was a prosaic case of private troubles, but it brought out the classic understanding of the philosophic and moral core of “love”—if love is taken seriously. And that is the point that has rendered so unrelievedly shallow the wave of complaints about Rudy Giuliani in his remarks concerning Barack Obama and the “love” of this country.

Running back to the Kobers, what if someone had professed to “love Hitler” because, say, of his magnetic qualities, his skills as a speaker, his devotion to Wagner’s music, and—crowning all—his aversion to smoking? That might indeed be the ground on which someone extends her love; and yet it would strike us at once as tellingly unserious. Unless, of course, we see “love” itself as merely the fancy of moment, implying nothing that may last beyond that moment. But, as Maggie Gallagher once observed so tellingly, “it is not free love but the vow that is daring. To dare to pledge our whole selves to a single love is the most remarkable thing most of us will ever do.”

Genuine Love Attaches to an Individual’s Character

After all, looks will atrophy with time. We may recall Shakespeare on Cleopatra: that “age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety.” To speak of a love that will last even as the body ages is to speak of the non-material bases of love: For we are speaking of something enduringly “good” and admirable in one’s partner, something that will persist even as beauty may fade. We must be speaking then of a good of character, a moral good. Mrs. Kober could not esteem or love what her husband loved, and the court found, in that moral objection, a sufficient ground to justify the annulment.

But the same moral grounds of attachment and separation must come into play in regard to nations as well. We can readily imagine someone who affected to “love” the Germany of 1933-45—the cuisine, the schnitzel and beer, the comradeship of Hitler’s Youth, the dramatic force of the spectacles, the torchlight marches, and mass meetings. But would that be a “love” that compels our respect? Or would it miss the point that has to be central: To love Hitler’s Germany was to love the character of that regime, the principles that it sought to impart in remolding the character of the German people.

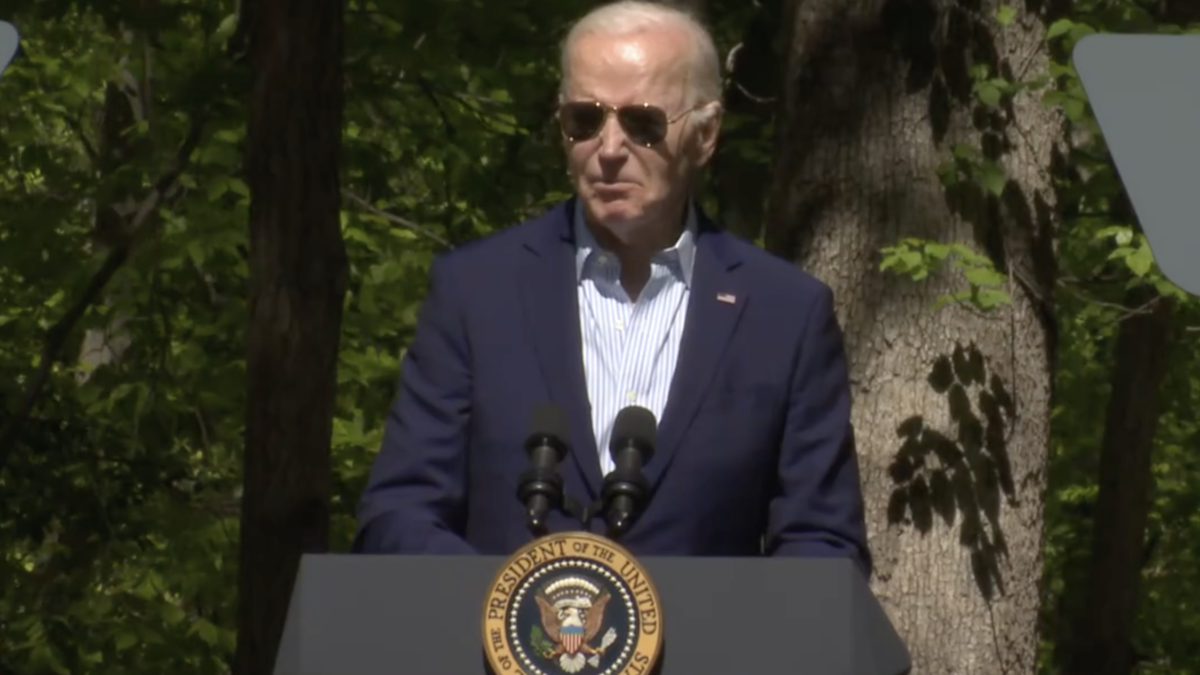

What would it mean, then, to ask whether Obama loves this country? Surely he would summon an affection for the country that elevated him to his high office—or at least to those voters who were willing to lift him to that station. But what of the regime whose defining principles made that election possible? For Obama, the country begins with the Constitution. But for Lincoln the nation began before the Constitution with the “proposition,” as he called it, that “all men are created equal,”—that the only rightful government over human beings would draw its just powers from the consent of the governed. As the understanding ran, one didn’t rule human beings in the way that human beings were compelled to rule dogs and horses. That proposition would hold true in all times and places where that nature remained the same and human were distinguishable from animals. As Lincoln said, that proposition stated “an abstract truth applicable to all men and all times.

Does Barack Obama Love This Country’s Character?

But Obama made it clear in his autobiography that there are no moral truths of that kind. “All men are created equal” was a high-flown sentiment, but not a truth, and for Obama the telling point was that the Founders who owned slaves did not truly honor it. But to say that people have not lived up fully to the principle is not to say that the principle is false. It was in fact the danger of making an acceptance of slavery in principle—and changing radically the character of the regime—that brought on the “crisis of the house divided” and the Civil War.

Obama constantly invokes the concern for equality, but unlike Lincoln and the Founders, he does not think that there is any moral truth anchoring that judgment. And if he is attached to the regime founded on those principles, it is not because there is anything in those principles themselves that command his respect as truths.

Obama has clearly found much to love in this country. He loves his friends and loyalists, he loves basketball and his favorite music, and the celebrities who welcome him to their homes. But by his own words, he loves something quite apart from the truths that were thought to mark the distinct meaning and character of this country. As Lincoln said, that “truth” of the Declaration was the “electric cord” that connected the generations. It explained why people could regard this country as theirs even though their families were not part of the generation that fought the revolution. It’s the thing that drew people to this country.

But it is not what has drawn Barack Obama to this country rather than to the land of his father, and, by his own avowal, it is not the thing he truly loves.