The Constitution of the United States was created with a simple purpose: to limit government. Imbued with various separations and specific endowments of power, the Constitution is America’s ultimate obstacle to government tyranny, higher and more powerful than any person, institution, or office.

This much we should already know from what passes for high school civics classes. But perhaps the most important aspect of the Constitution lies beyond where this common narrative ends.

Strictly speaking, our Constitution is pathetic. Now, its contents are fabulous — drawing on keen insights into human nature, desires to correct past mistakes, and profound conceptions of natural rights. But the fact still remains that our constitutional institution is extremely weak. It is but a long piece of old paper.

Even if Alexander Hamilton is still right and the judiciary possesses “neither force nor will,” at least it possesses that much of both, which follows from its human composition. The Constitution, on the other hand, is an old document — barely an entity, much less an institution in itself. One cannot reasonably expect scarcely visible words on paper to carry much weight against an executive with military powers or a populist legislature.

In that sense, the greatest of the Constitution’s institutional powers came after its writing, in the ratification process. By taking the fight over the Constitution directly to the people through state conventions — and circumventing state legislatures altogether — the Framers gave the people a personal stake in the outcome of their Constitution.

By doing so, they gave the Constitution its most powerful weapon against the government and embedded in the very heart of American identity a strong constitutional culture. Members of Congress, presidents, and justices on the Supreme Court would come and go, but as long as the American people existed, the Constitution would have every bit the power as it did the moment it was ratified.

Americans Don’t Know America’s Highest Law

This prized constitutional culture is dying fast and painfully. A study conducted last year by the Annenberg Center of Public Policy at the University of Pennsylvania showed that only 26 percent of Americans could name all three branches of government, while more than a third (37 percent) surveyed couldn’t name even one of the five freedoms or rights guaranteed by the First Amendment–religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition.

Former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia once lamented Americans’ ignorance of the Federalist Papers: “It is such a profound exposition of political science that it is studied in political science courses in Europe. And yet we have raised a generation of Americans who are not familiar with it.”

Indeed, most states’ history and civics classes today are “mediocre to awful,” according to a 2011 study published by the American Bar Association. When states’ standards for history classes were graded for “content and rigor” and “clarity and specificity” on scales from A to F, a whopping 28 states earned grades of D or F, while only 9 earned an A- or B.

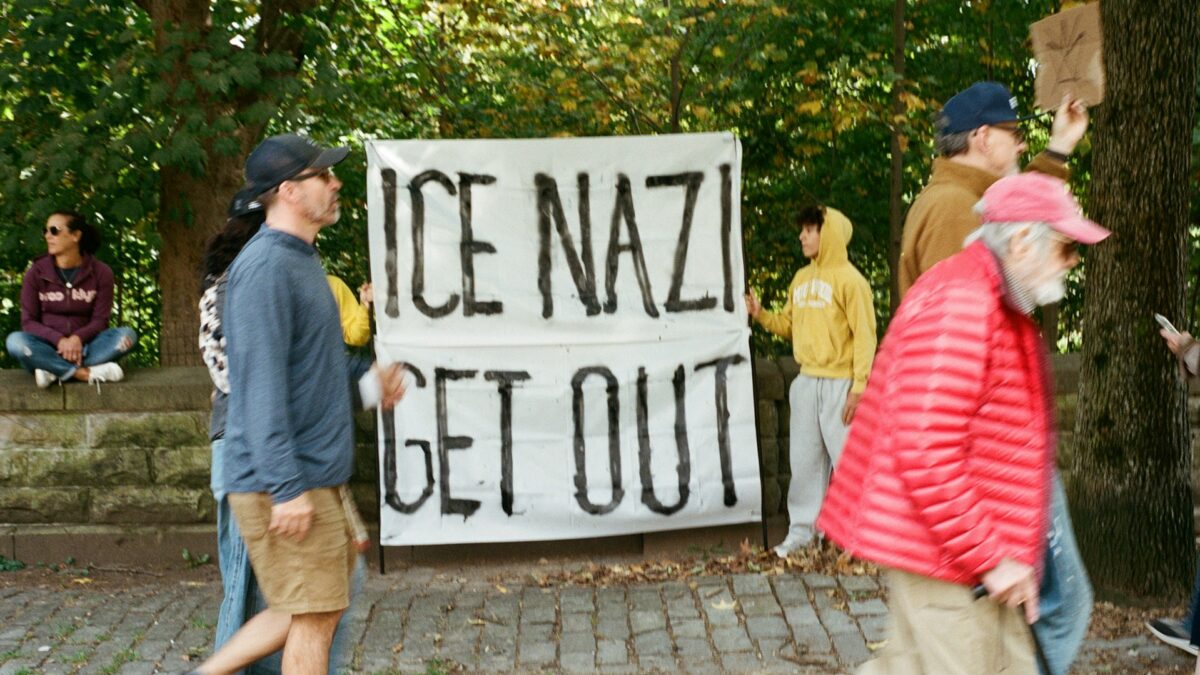

This self-destruction of our popular constitutional culture has gone hand-in-hand with another dangerous trend. With civic awareness at dismal lows, the people’s unique relationship to the Constitution has also been systematically usurped by lawyers and legal elites.

Starting in 1903 with Lochner v. New York and picking up the pace since, the legal class has been steadily dismantling public understanding of and access to the Constitution by introducing strange and novel concepts into constitutional interpretation that any well-informed common citizen would be hard-pressed to find. From substantive due process to “penumbras” and “emanations” of rights, lawyers have found new ways of convincing people that the Constitution has hidden meanings. We now live in a popular culture that is incapable of exercising the power it was given — the power it needs — because it has been wrenched from our hands and reclaimed by those we have come to regard as our intellectual superiors.

Legalese Obscures Our Understanding

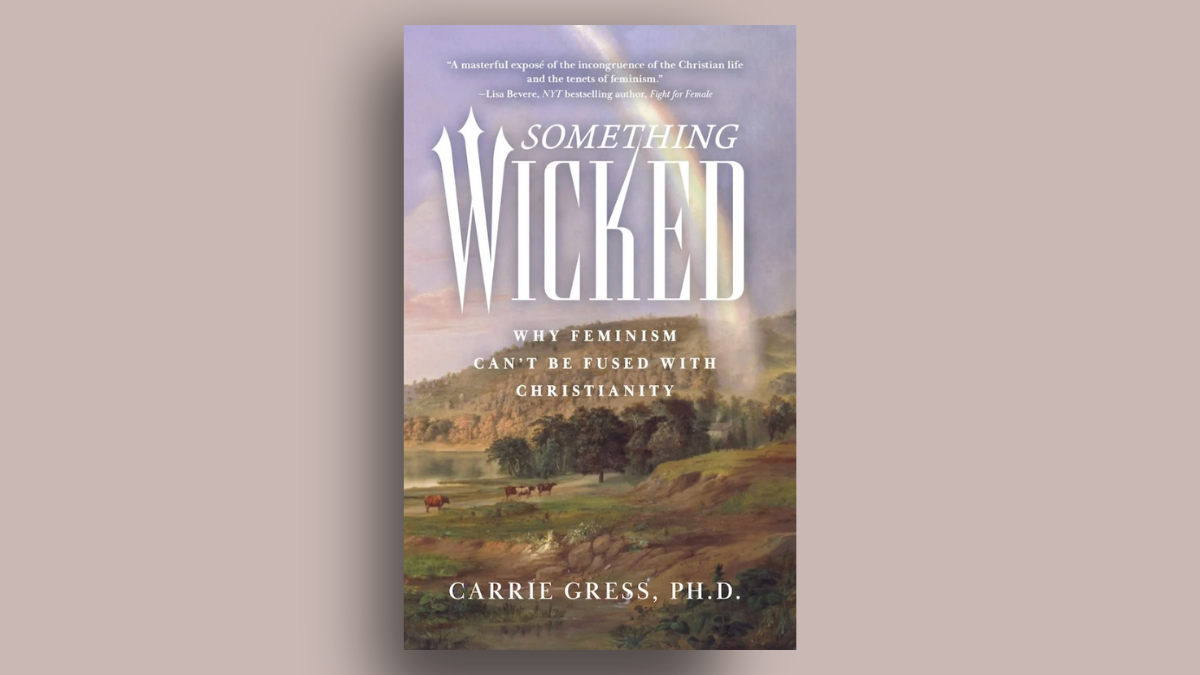

Surely, we think, only a genius could have the insight of substantive due process. Why not, then, leave these tedious intellectual duties of constitutional interpretation and our constitutional culture to these elites? Because our Constitution doesn’t have secret meanings, treasure maps, or numerical ciphers for Nick Cage to find with lemon juice and a hairdryer.

While lawyers and legal academics would like us to believe that only they can uncover our Constitution’s deeply hidden truth-gems, the fact is that the greatest of America’s treasures has always lain openly in the power of its people to control their own destiny. Our Constitution gives us exactly that — it was written for us and we were meant to render it a force with which to be reckoned.

The Framers believed that popular sovereignty, working hand in hand with our constitutional culture, would give meaning and force to the Constitution’s timeless provisions in a way that their mere words never could. But the dire state of our present constitutional culture strips our ultimate weapon of its power with every passing day.

How can we seriously expect to hold public officials accountable in the name of the Constitution when the overwhelming majority of us barely knows what it says? When we wonder why we see a scourge of assumed constitutional crises on the horizon, why our elected officials can misinterpret the Constitution and get away with it, or why our Supreme Court is composed exclusively of Harvard and Yale university graduates, there’s a simple answer. We have deprived the Constitution of its most potent power: ourselves.