What if Donald Trump is wrong? What if the Russia collusion investigation isn’t a witch hunt? What if it was a set-up—from the get-go?

That’s one—maybe the most—logical conclusion to reach after gathering the crumbs dropped over the previous two years in light of the Washington Post’s story last week confirming the existence of a “top-secret intelligence source” involved in the 2016 presidential election.

When the Washington Post ran its Wednesday story on the subpoena House Intelligence Committee Chairman Devin Nunes issued for information related to that intelligence source, it risked exposing the source’s identity. In an article for the Wall Street Journal, Kimberley Strassel highlighted the consequences of reporting on the leak:

Thanks to the Washington Post’s unnamed law-enforcement leakers, we know Mr. Nunes’s request deals with a ‘top secret intelligence source’ of the FBI and CIA, who is a U.S. citizen and who was involved in the Russia collusion probe. When government agencies refer to sources, they mean people who appear to be average citizens but use their profession or contacts to spy for the agency. Ergo, we might take this to mean that the FBI secretly had a person on the payroll who used his or her non-FBI credentials to interact in some capacity with the Trump campaign.

These specifics allowed Strassel to conclude that she likely knows the name of the informant, but because her intelligence sources would not confirm his identity, she did not publish it. Other journalists covering the Russia investigation have shared their belief that the details the Washington Post disclosed made it easy to finger the source.

The leaks to the Washington Post did more than potentially expose the source’s identity: it confirmed the existence of a “top-secret intelligence source.” That confirmation proves significant because it establishes that Fusion GPS co-founder Glenn Simpson’s August 22, 2017, testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee, saying the FBI had a source within the Trump campaign (or Trump organization—more on that shortly), was accurate.

While Simpson was questioned behind closed doors, Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) later released a slightly redacted transcript of his day-long testimony. One exchange that quickly garnered media attention occurred midway through his testimony, when Simpson explained that Christopher Steele, the contractor Fusion GPS hired to investigate Trump, met with FBI officials in Rome in September 2016 to provide them a copy of his now-debunked dossier.

“Essentially what [Steele] told me was they had other intelligence about this matter from an internal Trump campaign source and that — that they — my understanding was that they believed Chris at this point — that they believed Chris’s information might be credible because they had other intelligence that indicated the same thing and one of those pieces of intelligence was a human source from inside the Trump organization,” Simpson told the committee. Simpson added that the “human source from inside the Trump organization” was not one of Steele’s sources, but was “a voluntary source, someone who was concerned about the same concerns we had.”

A Very Misleading ‘Correction’

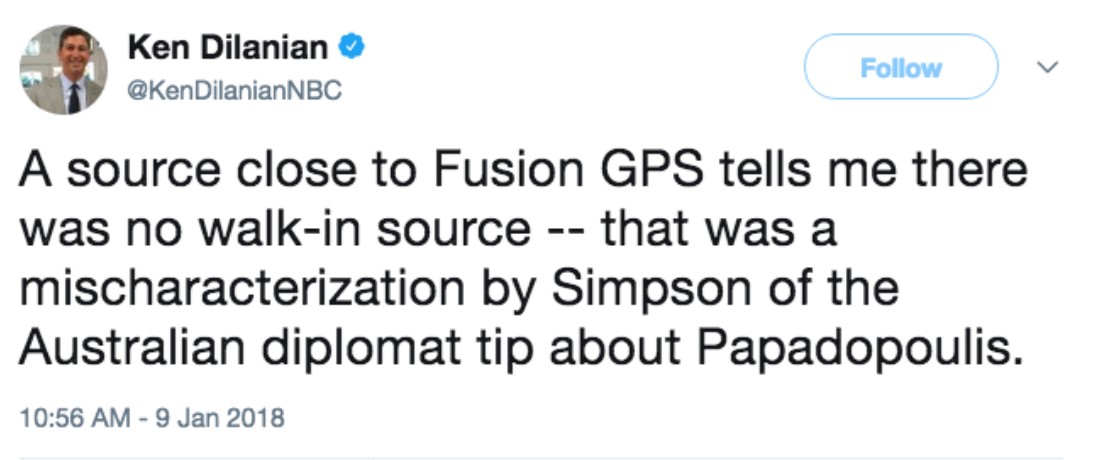

Initially, these details created a frenzy in the press, until, as The Federalist’s Mollie Hemingway reported, Ken Dilanian, an “NBC reporter who frequently helps Fusion GPS disseminate stories for its clients, said that ‘a source close to Fusion GPS’ had a correction to offer’”:

The Australian diplomat was Alexander Downer, whom many believe prompted the FBI to open the investigation into Russian collision in July 2016, when he told the FBI that an intoxicated Trump foreign policy advisor named George Papadopoulos had bragged that the Russians possessed thousands of stolen Hillary Clinton emails. (Andrew McCarthy questions that theory in his weekend National Review Online column, tracing its origins to a January 2018 New York Times article that infers the FBI learned of Papadopoulos’ boast from Downer or the Australians, but McCarthy notes that “there is no solid confirmation that this happened.”)

So, in its best “nothing to see here” counter, Fusion GPS latched on to that theory and painted the “source” Simpson mentioned during his congressional testimony as the Australian diplomat Downer. This purported correction quickly snuffed out the media’s interest in a supposed source within Trump’s inner circle.

In retrospect, it shouldn’t have. Simpson testified under oath before the Senate Committee, and is thus subject to perjury charges. In contrast, the “correction” came from an unnamed “source close to Fusion GPS” who leaked the purported clarification to a friendly reporter. Also, we now know from a story The Federalist’s Sean Davis broke that former Feinstein staffer Daniel Jones raised $50 million to hire “Fusion GPS and Christopher Steele after the 2016 election to push the anti-Trump Russian collusion narrative.” Davis also broke news that Jones intends to turn over all of his opposition research to the FBI and to publicly release it.

While the media en masse fell for the misdirection, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley was more savvy: He responded to the press reports that Simpson’s testimony was a “mischaracterization” by writing to Fusion GPS’s attorney and directing the firm to clarify (or correct) the congressional record. Simpson’s attorneys said “you have asked about the August 22, 2017 testimony from our client Glenn Simpson that Christopher Steele in the fall of 2016 said he believed the FBI had another source within the Trump organization/campaign. Mr. Simpson stands by his testimony.”

A second exchange from the hearing also established the “correction” was nothing of the sort. Toward the end of day’s testimony, an attorney questioning Simpson asked to clarify one point, noting “I believe you said that Mr. Steele had told you that the FBI had a source from inside the Trump organization and I believe [the attorney] referred to a source from inside the Trump campaign. Do you know which is accurate?”

Simpson responded: “I don’t know.” The attorney then rephrased the question, “So you don’t know whether it was the organization or the campaign, in other words?” Simpson responded, “That’s correct.”

This exchange makes clear that Simpson had not mischaracterized Downer as the source within the Trump campaign or organization. Rather, Simpson’s testimony establishes that the FBI had a source within Trump’s inner circle. We just don’t know if that source was connected to his campaign or the Trump business enterprise. We also know that the source was in place by, at the latest, September 2016.

When Did the Russia Investigation Begin?

The Washington Post’s revelation led Strassel to question when the Russia investigation launched, noting “[t]he bureau has been doggedly sticking with its story that a tip in July 2016 about the drunken ramblings of George Papadopoulos launched its counterintelligence probe.” When did this human source begin operating? Strassel asked: “If it was prior to that infamous Papadopoulos tip, then the FBI isn’t being straight. It would mean the bureau was spying on the Trump campaign prior to that moment. And that in turn would mean that the FBI had been spurred to act on the basis of something other than a junior campaign aide’s loose lips.”

Strassel’s on to something: Papadopoulos’ “loose lips” proclaiming “the Russians have Hillary’s emails” wouldn’t seem sufficient to launch an investigation against the Trump campaign given that, at the time, Hillary had admitted she had deleted 30,000 emails from her account because they weren’t work-related. Also, pretty much everyone acknowledged that with Hillary’s use of an unsecure homebrew server, the Russians likely already had accessed to those emails.

But did a source provide additional information justifying the Russia investigation? The case against Papadopoulos, who pled guilty in October 2017 to making materially false statements to the FBI, seemed to offer possibilities.

In pleading guilty, Papadopoulos stipulated to a 14-page statement of the offense that detailed his beginnings with the Trump campaign. On March 6, 2016, Papadopoulos, who at the time lived in London, spoke with a supervisory campaign official about joining Trump’s team. Papadopoulos further learned that improved relations with Russia would be a key focus of the Trump campaign.

The following week, while traveling in Italy, Papadopoulos met a professor also based in London. On learning that Papadopoulos would be joining the Trump campaign, the professor shared that he had substantial connections with Russian government officials. Over the next several months, the professor introduced Papadopoulos to different Russian connections. In turn, Papadopoulos shared updates with the Trump campaign about the Russians’ desire to meet with Trump’s team.

What the statement of offense didn’t mention was the professor’s identity. But after the court unsealed the guilty plea, the press quickly identified the professor as Joseph Mifsud. Mifsud admitted he was the unnamed professor, while maintaining that he had done nothing wrong. A little more than a year later, he vanished.

What Papadopoulos’s Girlfriend Knows

Mifsud’s disappearance prompted scores of articles, highlighting his background: his Russian connections, his professional work, and his personal life. He’s from Malta originally, and left behind his pregnant fiancée. But it wasn’t an article focused on Mifsud that proved the most enlightening. It was an article profiling Simona Mangiante, the girlfriend of Papadopoulos, who took to the media circuit after Trump dismissed Papadopoulos as merely a low-level campaign staffer.

Earlier this year, Mangiante told The Guardian how she came to meet Papadopoulos. In doing so, she exposed what may well have been the beginning of a sting operation:

Long before Mifsud and Papadopoulos ever met, it was Mangiante who was introduced to the mystery professor while she was working in Brussels, in the European parliament, as an attorney specialising in child abduction cases.

She was introduced to Mifsud in about 2012 by Gianni Pittella, a well-known Italian MEP who in 2014 became president of the Socialists and Progressive Democrats group. ‘I always saw Mifsud with Pittella,’ she says. Pittella had no comment. . .. When her contract expired, Pittella suggested she go to work for Mifsud in London, a city she loved. The professor offered her a job in 2016 at the important-sounding London Centre of International Law Practice.

Months earlier, Papadopoulos had joined the same London Centre for International Law Practice. Papadopoulos later connected with Mangiante through a LinkedIn message he initiated after seeing their mutual connection to the Centre.

The London Centre of International Law Practice was not Mifsud’s only enterprise. Mifsud also ran the “London Academy of Diplomacy,” where his friend Pittella was listed as a “visiting professor.” But it is not what Mifsud and Pittella did at the London Academy of Diplomacy that is worth noting. Rather, it is what Pittella did in July 2016: Pittella traveled to Philadelphia to, as he explained to Time magazine, “take[] the unprecedented step of endorsing and campaigning for Hillary Clinton because the risk of Donald Trump is too high.”

Of course, good friends can have widely divergent political perspectives, but this fact suggested another possibility: that Mifsud sought out Papadopoulos and recruited him to unwittingly feed the Trump campaign information about Russia and to see whether anyone acted on the advances. With this possibility in mind, I re-read the statement of offense Papadopoulos attested to, keeping in mind that the government drafted this language and cannot knowingly include false statements.

What Papadopoulos’ Statement Says Between the Lines

What we know, then, from the statement of offense is that Papadopoulos met Mifsud one week after Papadopoulos learned he would join the Trump campaign, but before that information became public, and that improved relations with Russia would be a critical focal point of the campaign. Following that initial meeting, Mifsud introduced Papadopoulos to a woman posing as Putin’s niece, and later, via email, introduced Papadopoulos to an individual in Moscow with purported connections to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

From March through August 2016, Papadopoulos continued discussions with these two connections, working to arrange a meeting between Russian government officials and campaign representatives. Papadopoulos regularly relayed these conversations to the Trump campaign. We also know the FBI obtained a judicial order to search Papadopoulos’ email messages, including those with Trump campaign officials.

Papadopoulos’ statement of offense also detailed his April 26, 2016, meeting with Mifsud at a London hotel. Over breakfast Mifsud told Papadopoulos “he had just returned from a trip to Moscow where he had met with high-level Russian governmental officials.” Mifsud explained “that on that trip he (the Professor) learned that the Russians had obtained ‘dirt’ on then-candidate Clinton.” Mifsud told Papadopoulos “the Russians had emails of Clinton.”

While Mifsud’s efforts to introduce Papadopoulos to various Russia connections do not necessarily raise any red flag, the same cannot be said of Mifsud’s statement that on a trip to Russia they told him they had dirt on Clinton—and thousands of her emails. There seem to be only two possibilities: Mifsud was lying, in which case he was trying to set Papadopoulos up. Or the Russians actually told Mifsud this, in which case he was working for them.

But for all of Mifsud’s Russian connections, and his statement that the Russians had dirt on Hillary and her emails, the FBI seemed extremely unconcerned. Mifsud told the press that he spoke to the FBI while in Washington in February 2017. While the FBI has not confirmed Mifsud’s statement, he is listed as a featured speaker at the February 2017 national meeting of Global Ties—an event sponsored by the U.S. Department of State. Mifsud then returned home to Europe, only to disappear in Rome nine months later.

What did Mifsud tell the FBI? He clearly isn’t the “source” referenced in the Washington Post article because he is not a U.S. citizen. But is he a source? Did he use Papadopoulos as a pawn to set up Trump? Did he feed Papadopoulos information about Russia to see how the Trump campaign responded?

If so, those efforts began in March of 2016—but on whose behalf? And for what purpose? Simpson testified before the House’s Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence that he didn’t know much about Mifsud. This statement seems to separate Mifsud from the Steele and Fusion GPS inquiry. But it leaves Mifsud solidly entangled in the earliest stages of the Russian investigation.

Given the FBI and DOJ’s stonewalling of the House Oversight Committee over information on the known “top-secret intelligence source” connected to Trump, one wonders what, if anything, they have told Nunes about Mifsud and the interview he gave the FBI before he disappeared.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that [a]fter learning of Papadopoulos’ position on the Trump campaign, Mifsud also offered Papadopoulos a position at the London Centre of International Law Practice as the director of international energy.” Evidence indicates Papadopoulos began in that position shortly before meeting Mifsud, but it is unclear how Papadopoulos received that appointment.