The Supreme Court ruled in favor of abortion proponents today, striking down a Texas state law that required abortion clinics to adhere to the same health codes as outpatient facilities and that all abortionists must have hospital admitting privileges.

In the majority opinion, the justices who ruled in favor of abortion advocates in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt argued Texas’s laws were in contention with a 1992 Supreme Court ruling (Casey) in which the court had determined that laws restricting abortions must not place an “undue burden” on a woman seeking to terminate her pregnancy.

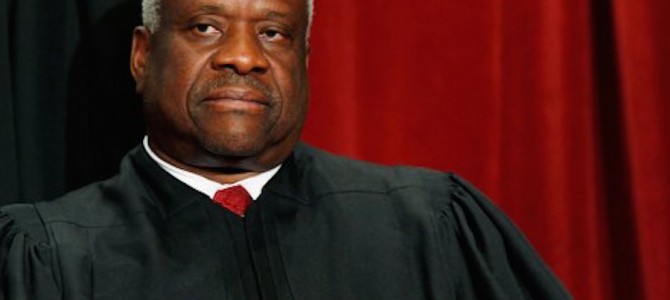

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a dissenting opinion ripping apart the court’s tendency to bend over backwards to accommodate abortion. Here are eight of the sickest burns in that opinion.

1. The court’s interpretation of “undue burden” is confusing as hell.

Today’s opinion does resemble Casey in one respect: After disregarding significant aspects of the Court’s prior jurisprudence, the majority applies the undue-burden standard in a way that will surely mystify lower courts for years to come.

2. Judges aren’t medical experts — even if they try to appoint themselves as such.

Moreover, by second-guessing medical evidence and making its own assessments of ‘quality of care’ issues. . . the majority reappoints this Court as ‘the country’s ex officio medical board with powers to disapprove medical and operative practices and standards throughout the United States.’ . . . And the majority seriously burdens States, which must guess at how much more compelling their interests must be to pass muster and what ‘commonsense inferences’ of an undue burden this Court will identify next.

3. Arbitrary standards mess up constitutional law.

As the Court applies whatever standard it likes to any given case, nothing but empty words separates our constitutional decisions from judicial fiat.

4. The court just makes stuff up to get what it wants.

The illegitimacy of using ‘made-up tests’ to ‘displace longstanding national traditions as the primary determinant of what the Constitution means’ has long been apparent. . . The Constitution does not prescribe tiers of scrutiny. The three basic tiers— ‘rational basis,’ intermediate, and strict scrutiny—’are no more scientific than their names suggest, and a further element of randomness is added by the fact that it is largely up to us which test will be applied in each case.’. . . But the problem now goes beyond that. If our recent cases illustrate anything, it is how easily the Court tinkers with levels of scrutiny to achieve its desired result.

5. Muzzling free speech? No problem. Defining marriage? Good luck.

Likewise, it is now easier for the government to restrict judicial candidates’ campaign speech than for the Government to define marriage—even though the former is subject to strict scrutiny and the latter was supposedly subject to some form of rational-basis review.

6. Made-up rights don’t trump those enumerated in the Constitution.

The Court has simultaneously transformed judicially created rights like the right to abortion into preferred constitutional rights, while disfavoring many of the rights actually enumerated in the Constitution. But our Constitution renounces the notion that some constitutional rights are more equal than others. A plaintiff either possesses the constitutional right he is asserting, or not—and if not, the judiciary has no business creating ad hoc exceptions so that others can assert rights that seem especially important to vindicate. A law either infringes a constitutional right, or not; there is no room for the judiciary to invent tolerable degrees of encroachment.

7. There are too many legal exceptions for made-up rights.

Our law is now so riddled with special exceptions for special rights that our decisions deliver neither predictability nor the promise of a judiciary bound by the rule of law.

8. Some may call the decision a victory, but it’s a loss for America.

Today’s decision will prompt some to claim victory, just as it will stiffen opponents’ will to object. But the entire Nation has lost something essential. The majority’s embrace of a jurisprudence of rights-specific exceptions and balancing tests is ‘a regrettable concession of defeat—an acknowledgement that we have passed the point where ‘law,’ properly speaking, has any further application.’

The decision is the most significant abortion ruling since the Carhart ruling in 2007, which upheld a federal ban on partial-birth abortions.