Solidarity—the concept that we have concrete duties to others with whom we share society, especially the poor and marginalized—has never been a word with much cachet in American politics. It’s not that Americans lack compassion for the poor; we appreciate the concept, but not so much the word itself.

Not only is this due to the importance of individualism to the American mythos, but it is also presumably due to the fact that the concept of solidarity is primarily associated with Catholic social teaching. And the relationship between America and the Catholic Church has been, to use the parlance of Facebook, complicated.

Nevertheless, the idea that we’re all in this together has consistently had political and moral force. Democratic politicians have historically been more at ease with this rhetoric (“Government is simply the name we give to the things we choose to do together.”), and so it shouldn’t be a surprise that the working and lower classes (and, to a lesser extent these days, Catholics generally) have been solid Democratic blocs.

This is not to say that federal bureaucracies are the only or best way to fulfill the idea of solidarity—only that liberal politicians wield the rhetoric most forcefully. Solidarity is neither a liberal nor a conservative concept, but a moral one. Conservatives, too, should adopt not just the language of solidarity, but its substance. We must recognize the dignity of the economically powerless by developing policy solutions designed particularly for their benefit; clichés and hand-waving about bootstraps and rising tides will not suffice, politically or morally.

This is a particularly salient opportunity because the current administration’s embrace of solidarity is one of style, not substance.

The New Deal and the Great Society, their wisdom placed to one side, were sold as social bargains in which general sacrifices were made to lift up the poor and marginalized. Obamacare, similarly, is at its most basic a social bargain in which the healthy accept sacrifices in the availability and cost of health insurance so that the poor and unhealthy can be covered.

Of course, we know that Obamacare was not sold this way. Though the necessity of helping the uninsured was a cornerstone of the president’s health care rhetoric, voters were disingenuously promised that everybody’s costs would go down and that everybody could keep their plans. It was solidarity without sacrifice, which is not solidarity at all. It was also, as we now know, impossible.

The social vision at the heart of Obamacare and of this administration, while adorning itself with the trimmings of solidarity, is in fact its inverse. Our leaders do not posit a cohesive society bound by mutual responsibility, only a collection of individuals loosely linked by reliance on the state. It is a hollowed-out solidarity, and state is quick to fill the void.

Nothing demonstrates this more clearly than the recent “Got Insurance?” campaign launched by progressive advocacy organizations Progress Now Colorado and the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative. Two ads have received special attention.

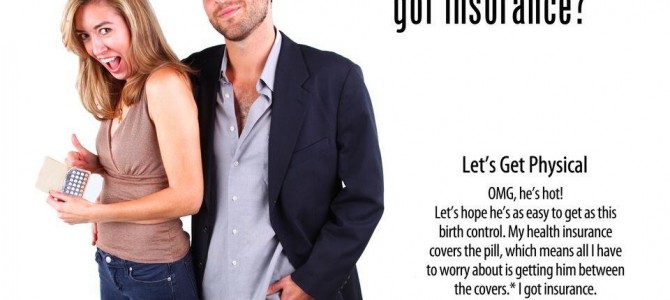

In the first, entitled “Brosurance,” the image is of three frat boys performing a keg stand accompanied by the caption, “Keg stands are crazy. Not having insurance is crazier. Don’t tap into your beer money to cover those medical bills. We got it covered. Now you can too. Thanks Obamacare!” The second, just released last week, features a flirtatious young woman displaying her birth control packet while sidling up to an attractive young man. The ad is called “Let’s get physical” and is captioned: “OMG he’s hot! Let’s hope he’s as easy to get as this birth control. My health insurance covers the pill, which means all I have to worry about is getting him between the covers. I got insurance. Now you can too. Thanks Obamacare!”

The “Got Insurance?” campaign thus far contains 21 ads targeting a variety of demographics, though young “millennials” are the primary marks. Ten of the 21 iterations tout the facilitation of twenty-something social life, six of which include alcohol pictured in the ad—and three of those specifically refer to saving money on healthcare in order to buy booze. By contrast, five ads feature children, only one of which includes a young parent with a child. And the mom in that picture looks like she’d rather be spelunking in Chernobyl than holding a sick toddler.

Now, it may seem unfair to lump the social vision of the Obama administration in with the marketing efforts of Rocky Mountain progressive activists. The president did not approve these messages. But if we look back to the 2012 campaign, we will see that the president marketed his policies in a strikingly similar way with the infamous “Life of Julia.”

Shortly after Mitt Romney became the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, Obama for America released an online slideshow detailing how the president’s policies would benefit a woman, Julia, over the course of her life. “The Life of Julia” is a snapshot of the president’s social vision: individuals tethered to fellow citizens not by the fibers of civil society and hardly even by family, but only by shared allegiance to and reliance on the state.

We are introduced to Julia at age 3 where she’s benefitting from the federal Head Start program, and there are no parents in sight. In fact, no other person appears in the slideshow until age 31, when “Julia decides to have a child,” much like she might decide to buy a Toyota. Her son Zachary, whom we meet going to a kindergarten which has “better facilities and great teachers because of President Obama’s investments in education,” presumably is fatherless.

From infancy to retirement, Julia is connected to no other person except her son, and even he disappears when she “starts her own web business” at 42. Her only relationship is with the state.

“The Life of Julia” is, of course, presidential campaign propaganda, and so we should expect a focus on federal interventions in Julia’s life. What is extraordinary is how alone Julia is. She has none of the connections or responsibilities that are intrinsic to natural human society. Her only duties are those which she chooses—even having a child is rendered sterile, framed as a discrete, consumerist, individual decision, rather than the natural result of forming a family with another person. And it is the state—specifically in the person of President Obama—that is promoted as enabling this alienation.

Now think back to the “Got Insurance?” campaign. The ads are not about fulfilling social responsibilities and liberation from want, but fulfilling personal desires and liberation from responsibilities. They, like Julia, posit a society in which we are responsible for no one and no one is responsible for us—except, in both cases, the state.

And whereas previous generations of big government advocates suggested that federal bureaucracies fulfill our own moral responsibilities to our fellow citizens, even that façade has eroded. It’s no longer about us taking care of our brethren through the medium of government so much as it is government, as an entity distinct from the people, taking care of all of us. (It’s possible that the latter is the necessary consummation of the former, but that’s an argument for another time.) There’s little by way of a moral appeal in “Life of Julia,” and certainly not in “Got Insurance?” We are invited to support this social program not because it is good, but because it is liberating.

Liberation from social bonds and duties is both the antithesis of solidarity and the garden path to statism. The only way we can both be free from social responsibility and live in a decent society is for the state to step in to fulfill those responsibilities. The vacuum of morality, authority, and power left by civil society will be occupied by the state.

Obamacare, as interpreted through these social sketches, thus presents us with the image of solidarity, but not its substantial reality. We could imagine a healthcare policy similar to Obamacare that at least took the concept of solidarity seriously—a policy accompanied by a social vision that accentuates our duties to one another in virtue of the inherent dignity we all share. Instead our leaders speak to the importance of helping the marginalized while simultaneously marketing an individualistic social ethic that insulates us from those very people.

Our choice is not, as is popularly believed, between individualism and collectivism; the former, as it dissolves the fibers of civil society, is merely an antecedent to the latter. Our choice is between civil society—specifically a civil society bolstered by a robust solidarity—and statism. Obamacare does not herald the victory of collectivism over individualism, but their alliance against civil society. Obamacare is not the fulfillment of solidarity, but its end.

It is a political and moral imperative, then, that conservatives do not cede the rhetoric and the substance of solidarity to progressives who use the rhetoric but undermine the substance. Voters can tell the difference. Sean Trende has persuasively argued (and I can anecdotally confirm from my perch in Pittsburgh) that Romney’s defeat can be traced in large part to his inability to attract the white working class. These voters felt that the president spoke to them but didn’t act for them, but that Romney did and would do neither, and so they stayed home.

Conservatives can’t condemn political marketing like “Life of Julia” or “Got Insurance?,” then pivot and peddle our own hackneyed individualism. We must be the voice for civil society, for social responsibility, for solidarity. We cannot let solidarity die, because with it will pass away limited government as well.

Brandon McGinley lives in Pittsburgh where he serves as Field Director for the Pennsylvania Family Institute. He and his wife welcomed their first child in July.