Spoilers.

In his memoir “Christ Stopped at Eboli,” Carlo Levi, the Jewish-Italian artist turned communist agitator, famously said, “The future has an ancient heart but a contemporary mind. What we need most of all is to have the courage to look at the past and grasp it, to understand it and to shape our future.”

Levi’s memoir is more preoccupied with reflecting on being a political exile in Mussolini’s Italy, but this quote rings true. The more Western civilization seemingly “progresses” (technologically, scientifically, etc.), the more detached we appear to become from its ethical foundation while becoming more aligned with various forms of pagan idolatry. At the same time, the ongoing explosion of technological secularism is destroying the philosophical and institutional mechanisms keeping the darker aspects of human nature, en masse, at bay. In many ways, it seems as though we are immersed in a Hobbesian state of nature despite our material prosperity.

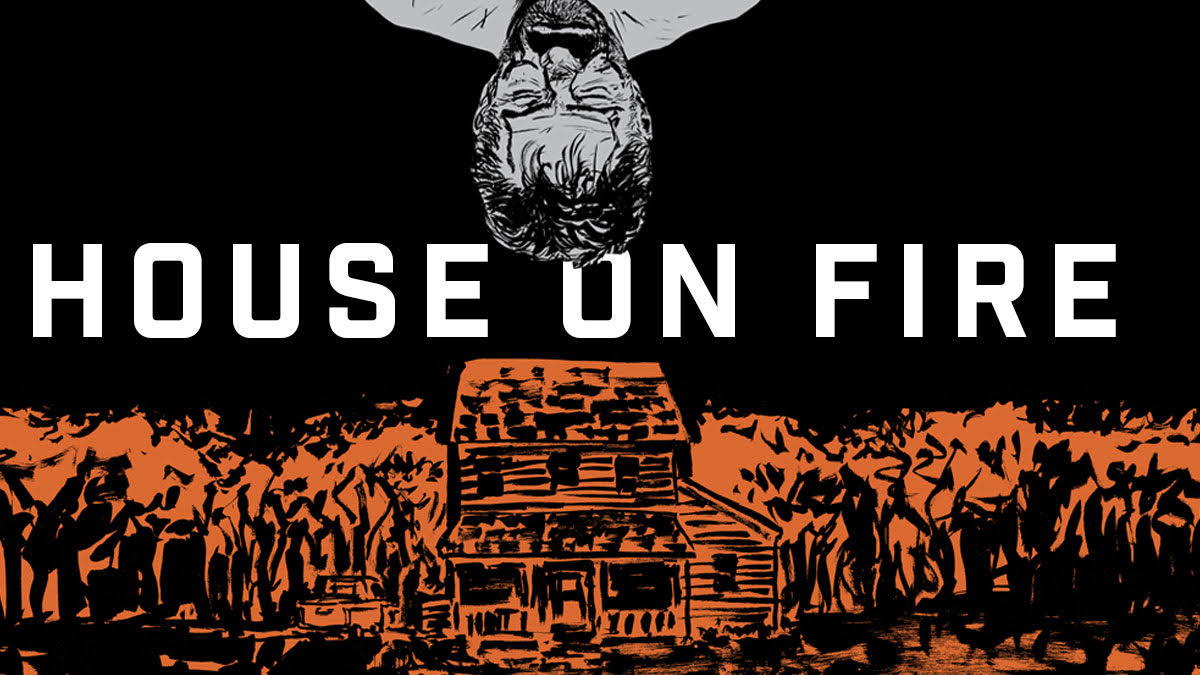

And this, in part, lies at the heart of Matt Battaglia’s debut graphic novel “House on Fire.” According to a synopsis on the back cover, the work is meant to “tease[] out the differences in a personal-political cruise through a fallen world, where fear is rational and obedience your only refuge.”

The piece follows an unnamed male protagonist as he ventures into a city blockaded by militarized guards (decked out with thermometer guns, respirator masks, and medical ID scanners) to acquire “shots” for his critically ill wife, who is stuck at home on some form of ventilator or respiratory apparatus. These guards regulate who enters the city, but it seems their more critical task is to control who exits.

[LISTEN: ‘House on Fire’: How One Graphic Novelist Explored Covid]

After bribing a guard and entering the city, our protagonist trades frozen steaks for his wife’s medicine on the black market. Evidently, beef becomes hard to find when the government prevents you from freely engaging with the rest of society.

Shortly after obtaining the medicine, the protagonist is jumped by two young adult men. He is thrown to the ground and stomped out as they try to steal his car, inside of which is his wife’s medicine. Pulling out a handgun, he fires a shot into the ground, indicating he is not afraid to use the weapon, but proceeds to offer them benevolence and tells them to run. Disregarding this warning, the young men charge him, attempting to take the gun, resulting in the protagonist shooting one in the stomach. He subsequently carries the young man to a place where he may spend his final moments overlooking a calming lake, removed from the urban violence to which he became accustomed.

The protagonist had to shoot the young man charging him. If he didn’t, he would have had his car stolen, been unable to leave the city or provide his wife with the medicine necessary for her survival, and would have also likely been killed or seriously injured. He had no other option, and the charity he showed these young men, who thought robbing him was an economically advantageous opportunity, was wasted.

Physically and emotionally distraught, our protagonist casts his gun into the lake and rushes home to his wife. On his drive home, he sees a doe on the side of the road, prompting the question: Is man truly free when forced to resort to his base instincts, stripped of the ethical framework that encouraged everyone to engage with each other in good faith?

Much like Tom Doniphon in “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” our protagonist is a moral man with the capacity for action. Because of the circumstances unfolding around him, he is forced to reacquaint himself with how man acts when in a state of nature so that he may return to a state of being outside of it — civilization. He has to set aside his humanity and compassion and embrace the animalistic instinct to pursue survival at all costs so that he may return to a world where compassion and humanity are universal.

After returning home, our protagonist sits on his front porch, reflecting on the day’s events and the world around him. He attempts to pray before heading back inside, and we are shown his house engulfed in flames — our souls and civilization are engulfed in flames and actively decaying because of the situations we are placed in and the decisions we are forced to make.

The world created by Battaglia in “House on Fire” isn’t too unlike the one in which we currently reside. After all, urban decay, street violence, and macro-ethical ambivalence are commonplace phenomena in our current society. The most significant differences between Battaglia’s fictional world and the real world are depictions of further developed systems of surveillance-based medical tyranny and beef scarcity in the United States.

“House on Fire” depicts what could have been if the “Black Lives Matter” riots, pandemic restrictions, and economic turmoil of 2020 continued unabated. And it’s entirely possible the reality depicted by Battaglia will come to fruition since he simply took a few of our more prominent, overlapping cultural woes and carried them to a natural conclusion: the atomization and reversion of man to depravity and the use of corrupt authority to sow anarchy among the masses.

The future, indeed, has an ancient heart.

Stylistically, “House on Fire” was crafted very conscientiously. The line work is fluid yet detailed, depicting the constant motion individuals must stay in to remain alive while also radiating the anxiety likely felt by the story’s protagonist. The tri-coloration also serves as an interesting motif. Black-and-white compositions present the world as bleak and lifeless — a world of systems, not people — and the orange-ish red that is used for shadows, thematic emoting, and more injects the story with an emphasis on hopelessness, rage, and decay but also on hopefulness, love, and commitment.

Human beings are complex creatures, and human nature is a complex thing. In “House on Fire,” Battaglia shows us how most people would react if they were pushed to their limit on a daily basis in a world where the systems required to maintain stability no longer incentivize man to pursue nobler goals.

“House on Fire” by Matt Battaglia is available wherever books are sold.