An astronomer would tell you Earth’s only natural satellite sits an average of 238,900 miles away. After this month, we could also say the moon is 50 years away from mankind.

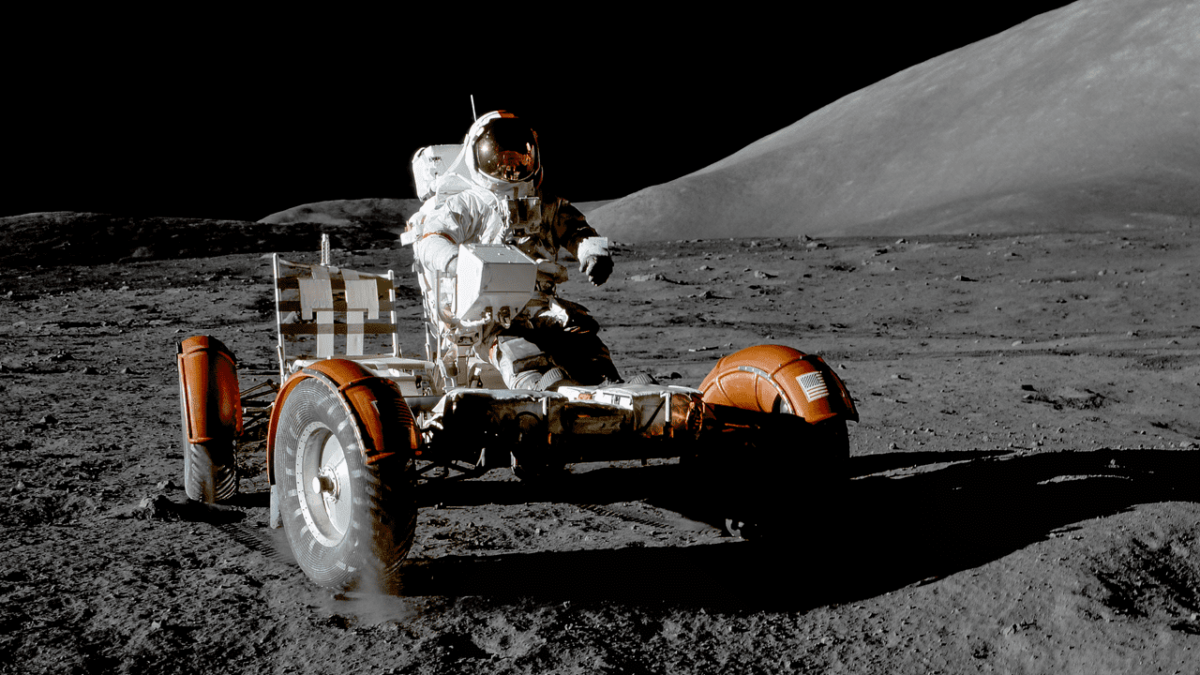

Half a century ago this month, Apollo 17 became the last manned mission to visit the moon — at least for now. Taking off in a dramatic nighttime launch early in the morning of Dec. 7, 1972, and returning to Earth 12 days later, the mission brought to a conclusion the Apollo program of manned lunar exploration.

Most of the current global population had not been born back in 1972, much less remember the occasion. Instead, artifacts like the overshoes of Gene Cernan, the last man to set foot on the lunar surface, at the newly renovated National Air and Space Museum must suffice to recount the history for today’s generation.

In his concluding comments during Apollo 17’s last spacewalk on the moon, Cernan said man would return “not too long in the future.” Time has disproven his prediction, and Cernan died five years ago still holding the title of “the last man on the Moon,” which says much about America now as the Apollo program did back then.

Kennedy Era of ‘Big Government‘

The Apollo program had its roots in President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 pledge to land a man on the moon and return him safely to the Earth by the end of the decade. The pledge had dual political appeal for Kennedy: First, as someone who had spent the 1960 presidential campaign talking about a (nonexistent) “missile gap” with the Soviet Union, joining the Space Race by issuing a bold challenge demonstrated strong leadership. However, a cynical observer would note that Kennedy would have had to relinquish the presidency in January 1969 regardless —meaning that, even had he lived, he would have faced little accountability for failing to deliver on his promise.

The hundreds of thousands of engineers, contractors, and government employees who worked on Project Apollo represented the optimism of Kennedy’s New Frontier. To borrow the metaphor of Kennedy’s inaugural address, a new generation of Americans appeared ready to lead the United States, and the world, to big achievements for the betterment of mankind.

But by the time of the first lunar landing, let alone the final mission of Apollo 17, those halcyon days looked far distant. The proverbial “best and brightest” had dragged the United States into a quagmire in Vietnam that cost American lives and prestige. Rioting and violent crime plagued major cities, with anxious families fleeing to the suburbs. Kennedy’s goal was achieved, so space exploration began to take a backseat to solving problems closer to home on Earth.

Space Program Adrift

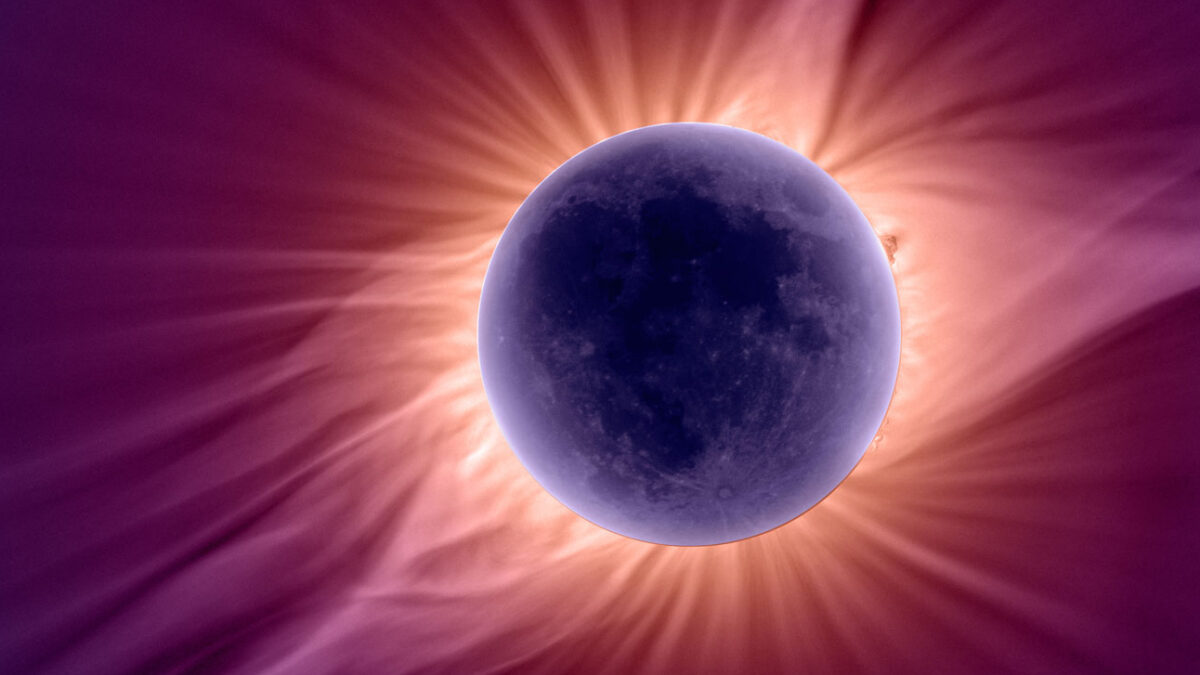

In the 50 years since, manned space exploration has lacked direction. The Air and Space Museum’s newly installed display proclaims confidently that “people will visit the moon again in the 2020s,” a sentiment recently echoed by NASA Administrator Bill Nelson.

But call this observer skeptical that a government space program long plagued with bureaucratic delays, budget overruns, and institutional neglect can finally deliver a project on time and budget. More to the point, the public at large knows little about a potential return to the moon and might care little even if it did.

Apart from the jaded, self-centered nature of our society in the social media age, the space program’s drift over half a century reflects a federal government that tries to do too many things and often ends up doing many of them poorly. It does not seem a coincidence that the Apollo Program began in 1961, four years before the creation of Medicare and Medicaid — two programs that in the fiscal year ending next Sept. 30 will consume just under $1.5 trillion of the federal fisc.

As those two programs (as well as Social Security) have grown inexorably over the past five decades, the share of the budget dedicated to programs like space exploration has continued to decline. While America’s unsustainable entitlements have brought the country closer to fiscal Armageddon, it might have created a silver lining when it comes to manned spaceflight.

Private Exploration

In the past several years, private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin have revolutionized space exploration, lowering launch costs and sparking a nascent space tourism industry. These developments have made the NASA-centric model — of 400,000 or so government contractors and billions of dollars in funding from Congress — seem as old as, well, the Apollo Program from which the model came.

We can and should continue to explore outer space, both for practical scientific knowledge and the sheer wonder and awe of discovery. But it shouldn’t take a massive infusion of taxpayer dollars to do so. And if the federal government stopped trying to do so many things, like civilian space exploration, that the private sector can do better, perhaps it could use more of its scarce resources to focus on issues actually within its purview, like keeping the public safe and enforcing our borders on Earth.