If probing collusion between government officials and their allies in the corrupt media counts as trolling, then call me a troll. At least, that’s how Interior Department spokeswoman Melissa Schwartz described The Federalist’s attempting to use open records laws in a September text to New York Times reporter Coral Davenport last year.

After a source relayed that The New York Times was courting a reluctant Interior Secretary Deb Haaland for an explicitly friendly profile, curiosity led me to request emails between agency staff and the Times through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). The results were striking. Emails showed the paper taking direction from administration officials and functioning as a government PR department — especially when compared to how the same reporters covered President Donald Trump.

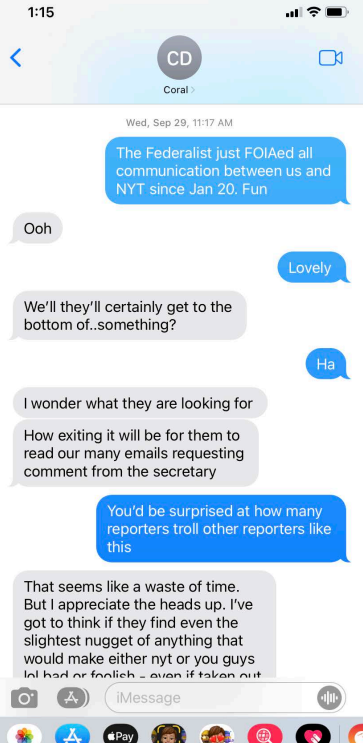

“The Federalist just FOIAed all communication between us and NYT since Jan. 20,” federal employee Schwartz wrote to the Times’ Davenport in a text on Sept. 29, 2021. “Fun.”

“[Well] they’ll certainly get to the bottom of..something?” Davenport wrote back.

The text message was unearthed in a separate documents request this fall by Protect the Public’s Trust (PPT), an independent government transparency group that shared the exchange with The Federalist.

“You’d be surprised at how many reporters troll other reporters like this,” Schwartz told Davenport.

“That seems like a waste of time,” the reporter replied. “But I appreciate the heads up.”

Davenport didn’t write the profile that sparked my search, but her fawning treatment of Democrat-run government activities was a key finding.

In August last year, Davenport, who covers energy and the environment for the Times, inquired about a court appeal from the administration on energy leasing. The date of the email, Aug. 16, 2021, suggested Davenport was asking about the Interior Department’s move to block a judge’s order overturning the White House ban on federal oil and gas leases.

“I’m trying to understand what exactly is new – the decision already required the administration to resume leasing,” Davenport wrote. “We will not do a story about the appeal – I’m just trying to understand what, beyond the appeal, is substantively new.”

Schwartz asked Davenport not to continue with the story.

“More than happy for you to not write,” wrote the agency spokeswoman.

No story was written on the topic under a Davenport byline in the days following the exchange, according to New York Times archives under Davenport’s name.

In another email to Schwartz a month later, Davenport apologized for asking questions.

“Sorry we are so annoying w oil & gas lease Qs,” Davenport wrote. “Could you give a call? Interested in what else might be coming down the pike.”

Earlier this month, Chris Horner, a D.C. attorney affiliated with the libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute, highlighted in The Wall Street Journal how federal agencies routinely skirt public transparency laws. Government employees, Horner wrote, often use private phones or encrypted messaging apps that typically go unsearched unless specifically included in records requests.

The issue here isn’t that the Department of the Interior deliberately tried to conceal communications from my own FOIA request, which remained narrowly tailored to emails the agency disclosed in compliance with the law. But Horner highlighted in an interview with The Federalist another resistance to compliance with transparency laws across the broader administration.

“Favored outlets get ‘tipped off’ to FOIA requests while actual FOIA requesters struggle even to get CREW acknowledgments in 20 working days,” Horner said.

Under the Freedom of Information Act, agencies are required to respond to records requests within 20 business days absent “unusual circumstances.” In 2013, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the legislative requirement that agencies are required to give a substantive response to records requests within the statutory time frame in Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington v. Federal Election Commission.

Last week, I followed up with the Interior Department’s Office of the Solicitor on another open records request about an issue in Alaska’s King Cove. The request was submitted on May 11, and I only received a follow-up email with a suggestion to narrow the search on June 23. I agreed to the changes but have heard nothing back after following up for an update again on Friday, more than four months after the initial submission. Two more open records requests with the Bureau of Land Management, also submitted on May 11 with a supposed due date of Thursday, seem to have gone unnoticed, with no response beyond an automatic-reply acknowledgment.

This article has been updated since publication.