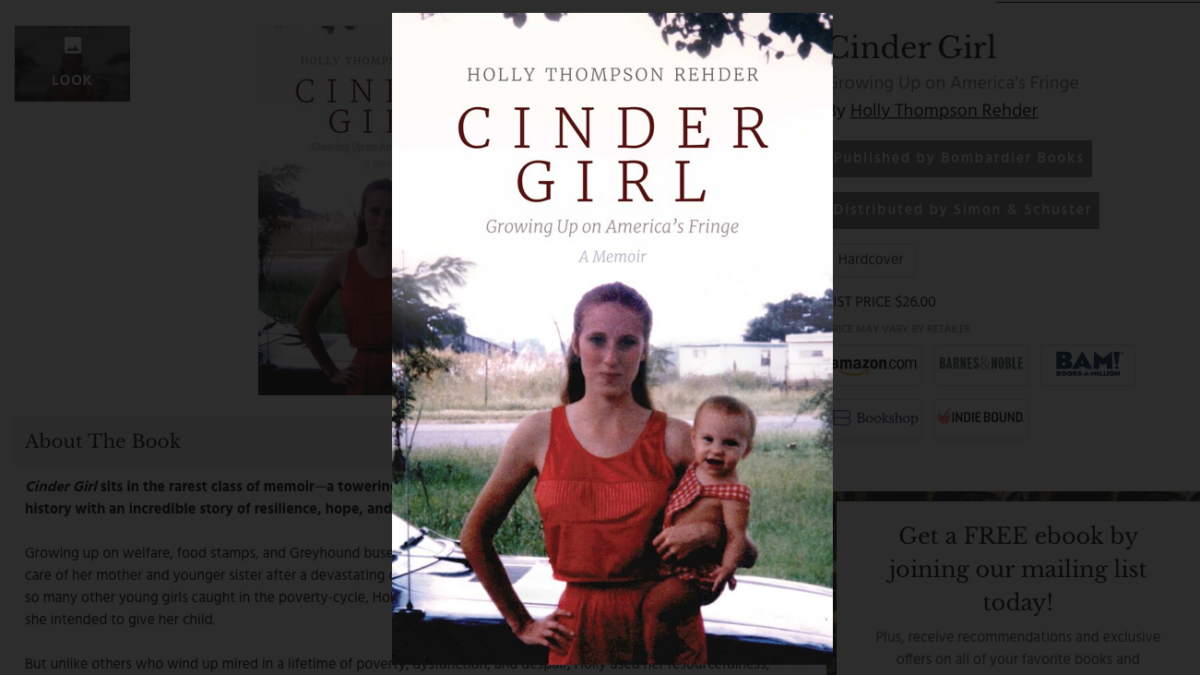

The following is a rush transcript of an interview I conducted recently with Missouri state Sen. Holly Thompson Rehder, a Republican who represents a chunk of the state’s southeastern area. Thompson Rehder is out with a striking memoir called “Cinder Girl: Growing Up On America’s Fringe” that documents her journey from a troubled childhood growing up in trailer parks, becoming a teen mom, and eventually finding her way into politics.

Thompson Rehder’s perspectives on institutional distrust, addiction, media, Donald Trump, and classism in politics are completely underrepresented in our national discourse. We talked for nearly an hour, and while the transcript is lengthy, I think it’s well worth reading, especially as an example of the voices our political establishment turns the volume down on, and especially as the conservative movement scrambles for ways to repair America’s tattered social fabric and nudge the GOP to represent a more working-class base. Thompson Rehder’s experiences with welfare and single-parent households are invaluable illustrations.

“Cinder Girl” takes its name from “Ever After,” the 1998 film starring Drew Barrymore, which Thompson Rehder counts as her “favorite movie.”

Emily Jashinsky: I know that the purpose of a memoir is to explain kind of how your life has unfolded. But since it’s your first time on the program, could you give us basically an overview of how you ended up where you are right now, as a Republican state senator in Missouri?

Holly Thompson Rehder: Yes, so I was raised quite differently from what you typically see in politics. I was raised on welfare, single-family home, or single-parent house. My mother struggled with mental illness her whole life and went through many abuses like domestic violence, drug addiction. When things would kind of go south, Mama would just put us on a Greyhound bus, and we’d head to the next location.

I moved over 30 times from the end of my third grade to the beginning of my tenth. And when I had to quit school at this time to help take care of my family. So, I became a mom at 16, and that’s kind of the base of the memoir that I take you through many mountains and valleys. How that turned into me being in politics, which is still so wild, in my opinion, but my husband and I had started our own company, and I had worked for corporate office of a cable television company.

For many years, I was the director of government affairs. I worked my way up to the mailroom, and I began being asked to come to Jefferson City to our capitol to work on a bill that affected our business, affected our industry. That was my first view of politics. And I thought, you know, we have a lot of attorneys here, which we absolutely need, but we need people with different life experiences that could really speak to things that Republicans aren’t speaking to. But– but we have the policies that actually bring people out of poverty. I’m a product of it. And so, that was very important to me to have, be a voice for my community where I grew up, which is the trailer park, but also a voice for people to know that you can absolutely break that cycle of poverty.

EJ: And, you know, that’s– it’s an experience that so few people actually have in politics and one that gives you a completely different perspective. Now, could you take us a little bit through the memoir? The first chapter is Texas, and you have this incredible story, starting there. So could you just, I know it’s sort of hard to ask you to– to truncate your memoir, folks should absolutely buy it…But could you tell us a little bit about where this all really begins for you?

HTR: Yes, so I was– so I was born in Memphis, and my mother and biological father divorced shortly thereafter. She married my little sister’s daddy, and we moved to Dallas. And so, at two years old, two to three years old, I was living in Dallas, where my little sister was born. And that’s kind of when my memories started as a person and– and me recognizing my mother’s mental illness, her manic depression.

Of course, I didn’t know what it was. We just knew that mom was really sad a lot. But then some days she was absolutely over the top. And that’s when I started seeing the different men coming in and out of our home, mom and dad splitting up, then us moving to Garland. Back again with a beautiful American family, you know, three daughters, daddy and mama in the same home.

But then it all goes south really fast, and we had to leave in the middle of the night, go to my grandparents’ home in Southeast Missouri, which is when my life absolutely changed from a middle-class home with a mama and daddy — and a daddy that balanced a lot of times mamas highs and lows — and into really just the poverty-stricken part of Southeast Missouri, which is where we lived and staying with family at times because we were homeless, because we moved so frequently, right? And go into many different schools. And then, I mean, we moved from California to Florida, back to Texas many times. And so that’s kind of where it all starts. And I just talk about those, those highs and lows, and the different things associated with drug addiction, mental illness, and poverty, and hopefully give some advice on how we can do things a little differently, you know?

EJ: Oh, absolutely. You write about sexual abuse. And I wanted to ask from your perspective, because in the book, you write that your mother’s mental illness — you wrote that she struggled with sexual abuse. And I wonder if you saw, it seems like an obvious connection to make, that that was a source of mental illness for her that that was part of what kind of tortured her mentally? What role did that play in sort of the dominoes in the chain of effects going forward?

HTR: You know, and I didn’t — I didn’t connect all those dots until I was an adult, unfortunately. She talks about it often. And I think that hearing the gruesome details, as a child, either callused me or I shrugged from it because it was so awful that I didn’t want to hear about it. And maybe just having a child’s brain I didn’t understand and how much that had to do with how her responses to situations were. But as an adult, when I started realizing her whole life, I mean she had been taught that her sexuality was her self-worth. That was what she had to give. And her actions absolutely had told that story my whole life. I didn’t get it, get it.

EJ: You write a lot about your faith. And I wanted to ask, this is a pretty obvious question, because it plays a role, a significant role in the book. But how did you sort of come to faith, and how did that help you through all of this?

HTR: It was my help through it all. And you know, at four years old, which I think is pretty odd, at four years old, I started going to church with my neighbor and riding the church bus with her. And I just knew Jesus was just in my heart. And — and I knew that that’s who I spoke to when I was hiding under the bed. I knew that’s who I had come to growing up. And then my grandparents were Seventh Day Adventist. And so when we did move to Southeast Missouri, I clung to being at my grandma and papa’s. And so I was in church every weekend that I could. When we would move, I hated not having that connection. But as long as I can remember, I’ve spoken to God. And I’ve relied on him and asked for guidance. It’s just been an incredible part of my spirit, as far as I can remember.

EJ: It strikes me that you started going to church with a neighbor. And somebody who is in politics right now, it does seem to me, especially in rural areas, that people have less and less of those neighbors who are taking them to church, where they’re not as close with neighbors who might just, you know, by happenstance say, “Hey, come on, we’re going to church,” something like that. Looking at the landscape now, do you worry about that at all? Do you worry that, you know, some of the social fabric that was able at different points in your life to kind of catch you a little bit, do you worry that that’s kind of fraying for a lot of people in 2022?

HTR: I do. I absolutely do. And that’s an interesting question because I haven’t thought about that. But absolutely, you know, one of the things that I made sure, just once I got old enough, probably 8 or 9, to be able to figure out where the Vacation Bible Schools were. You know, that was my favorite part of the summer. I would go to many vacation bible schools that I could walk to. And you just don’t see those being advertised as much. You don’t see as much of that community bringing the kids in. Now I live in a very small community, 5,000 folks, and I know the churches have signs up, and they do all that. But absolutely in some of the larger communities, I know our kids are missing out on some of that. As, as you said, that really was my safety net.

EJ: I also wanted to ask, there’s so many — it’s interesting because your story is almost prescient in that you experienced so many things in this childhood that are bigger issues even now. You know, mental health, opioids, or pain pills, all of these things that played a role in your life and the lives of those around you are huge now. Community, faith, all of that, you know, faith continues to go down. Opioid use, it’s hard to see an end in sight to the opioid crisis. Could you talk actually, just about it from — from your perspective, watching the country basically be ravaged by the opioid crisis? What it is that is so incredibly, I guess, tempting and seductive and addictive about opioids?

HTR: Look, the 33-year-old mama that was dealing with it from my child, becoming an addict, absolutely did not get this. The 50-plus-year-old mama that the legislator and his work with specialists now for many years, I’ve had the great fortune of having some of the best in those trenches. They explain things to me. And it has — 50 percent of it has to do with our DNA, which is why you see alcoholics running in families, drug addicts running in family. I can take a — I have migraines, and from time to time I can take if my medication isn’t working, I’ll have to take an opioid, to knock the pain. If I have to take an opioid more than two days, I have to wean myself off of it because my body attaches to that and stops making its own endorphins.

So you think — and then age, and of course, environment makes up the other 50 percent. If you take a child who has my DNA, who’s already susceptible to addiction, and they get their wisdom teeth out at 16 or 17, and that dentist gives them a script of some form of an opioid, which used to be very normal and might still be in a lot of areas, that young brain, 30 percent of kids who take opioids before their brain is completely finished developing in their 20s will become addictive by the time they’re 25. But it’s — the statistics are staggering. And it’s because it literally changes the pathways in your brain. I had a neurologist, or neuroscientist, show me one slide of someone’s brain on opioids that was — had my type of DNA, addiction, and someone who didn’t, both on opioids. The slides of the person who didn’t have it had a few lights lit up. That slide was the person who had addiction in their DNA makeup, it was lit up like a Christmas tree.

And so you take that, and then 20 years ago when our doctors are being told these are not addictive, so they were writing them for every mining injury, every workplace injury, or football injury per kid on a field, in high school. And — and then when they get addicted to that medication, they just have to have more and more because there’s a threshold of pain, and they have to have more medicine to knock that. And that’s why you see 75 percent of heroin users started with opioid addiction. It makes perfect sense. Why was this tsunami now, but we didn’t see it coming.

EJ: And in rural areas and in lower-income areas, what do you think it is? I mean, obviously, the opioid crisis has spared no community, you know, urban community. I live in an urban community that’s very much affected by the opioid crisis. But in rural communities, I think it took a lot of folks by surprise when they realized how bad it had gotten. What is it, what sort of variables in your opinion, when you look at despair, [inaudible] of despair, when you look at people turning towards opioids, or you look at suicide spiking? What from your perspective, as somebody who’s lived a lot of this is, is combining into this really lethal cocktail for so many people in rural communities?

HTR: I think that the hope is pretty low. In communities like mine, in the trailer park area, and, you know, I mean, and not outside the parks, I don’t, I don’t mean to just, I mean, the ones I grew up in that, you know, we’re — we’re very much transient population, like we were. And hope is just very low. And when you have, you know — I didn’t see someone working in my home. I didn’t grow up with someone who worked. All of those types of things, working, being out in the community, being productive — all of that is helpful when it comes to your natural endorphins, knowing to work out all of these things, knowing to take care of yourself. It’s the opposite in the transient population I grew up in. You’re not working. No one in your home is working. The parents aren’t really checking to see if the kids are going to school. It’s — you’re just lacking hope.

And many times when you get injured on the job, and you get put on these medications, I mean — nobody wants to be a drug addict. That’s not, you know — when I go speak in high schools and say, “Hey, what do you want to be when you grow up?” no one raises their hand and says, “I want to be a drug addict.” But different paths take you into that. And once you’re in it, it controls you. You’re just trying to get the next medication to help take the pain away. Because you — when you start going through the withdrawals, you sink into deep, deep depression. You have your pain that shoots up, and you just feel like you have no energy. It’s like flu-like symptoms, but the — the depression. And so, and honestly, when you get clean, it takes about two years for your brain to heal itself, and for you to get beyond that deep, deep depression. And I think you see a lot of people who don’t realize that that does go away, who think that that’s their life now. And some people choose to end it.

EJ: Now, can you talk to us about Papa and the role that he played in your life? Complicated, very complicated role, and what it’s like for you, I guess, to have a — it’s sort of been an interesting theme in our culture in recent years is figuring out how to deal with complicated people and to reckon with people’s, you know, the difficulties and the different dimensions of who they are. Talk to us about Papa and your experience.

HTR: I think that, you know, I wrote my “Me Too” story and published it years ago when — when we first — when that first started coming out, and being the light shone on it. And I started getting calls from other people and realized that those complicated relationships are very prevalent. And, you know, I love my grandfather, he was the rock for me. After my grandma died, he was the one that I knew I could go to his house and feel, and I would have a comfortable roof over my head. I would have air conditioning or heat. I would be taken care of. There would be food in the refrigerator. I could mow his yard and earn some money if I needed something for school, like if we were doing a bowling day or something and I didn’t want to be sitting out like I always did, you know.

But when he molested me, it just shattered my world. And it was hard as a child to understand. I hated him, but I loved him. And — and I guess I’d maybe never, never have understood it other than that’s just how God has made us. You know, you can’t turn love off. You can’t turn off all the good things somebody has done for you, no matter how bad you’re hurt. And as a child, I just couldn’t reconcile that. I couldn’t understand how he could do that to me. I was, I was his baby. I mean, I knew I was the one he loved. And then as, as I got a little bit older, and he got cancer, I mean God is, I tried to do what God wants me to do. I want to be pleasing to God. I don’t care about being pleasing to man. I want to hear, “well done my good and faithful servant” someday, no matter what. And so, I knew that I had to help him, and it was mine to do. Nobody else would do it. But that was one of the best blessings in my life, is God allowing that pain to heal because I was forced to be with him. And I was — it gave him the opportunity to show me how sorry he was, and it gave me the opportunity to let that heal. No, not ever be okay with what he did, my family had pushed those things under the rug. I can’t understand that. But unfortunately, I’ve heard from many victims, that had said that their families have done the same.

EJ: Do you look around ever and wonder how so many people who, who have similar stories, deal with it — without faith, without Christ? I mean, your story is a great example of how that was a healing path out of just incredible trauma and darkness. It just seems to me, I don’t know how so many people could endure that pain, and maybe they’re not without that sort of route to healing and without faith.

HTR: That’s what I feel. I feel that they’re not. You know, I feel like that’s a lot of the mental health issues that we see today. Are people that just haven’t been healed, that they’ve not found that wholeness yet, and that they’re tormented still, by what has happened to them, and rightfully so, you know?

EJ: Absolutely. And have you found writing about all of this to be — obviously difficult, but therapeutic in any way, or is it just difficult? I don’t mean that as a leading question, but is there something — because you mentioned you wrote the Me Too story, you’ve written this story as well, obviously, in a longer format? Is it helpful for you?

HTR: It really has been therapeutic. I didn’t think that it would be. I thought I was fine, but there’s a ton of it that was very soul-cleansing, and I’ve always loved to write. I’ve always — I write all the time, just in journals. And I absolutely recommend it to everyone that has been through these things, because I think putting it to paper, getting it out, and it’s a form of relief and letting go and just soul cleansing.

EJ: It’s been an interesting politically and interesting 10 or so years, to watch the Republican Party, you’re a member of the Republican Party, take on a more working-class base and to speak, I think, more directly to members of the working class, and to try to devise policies that will be, you know, more helpful or more appealing to the working class. And I wonder, your — your epilogue is titled, “Reluctant Warrior,” which I think is really interesting, because you know, so you started talking about how you don’t care, you don’t care about being judged by man. You’ve been through it all, and so that doesn’t really have a hold on you. Tell us first, as we shift kind of to politics, why you decided reluctantly to enter that sort of arena.

HTR: You know, again, I really felt it was a draw on my spirit. I really felt that God was opening those doors. And I’ve always been someone, it doesn’t matter how crazy the door looks, and that was absolutely crazy for me. I mean, I’m dyslexic. As you know, I quit school at the beginning of 10th grade. I had to take my GED, took me 17 years to get my college degree because I was doing it with raising babies and working more than a full-time job. And politics, I’ve never, until I started working on that bill, I’ve never even been familiar with it. I was in survival mode. But then I started having that draw, and this, God telling me to check this out. And then He opened door, after door, after door for me to get in it, which was odd again.

But I really felt like, when I saw it with my own eyes, these are the people who are deciding where my tax dollars go and how much I’m paying in taxes. And so often in politics, compassion overrides common sense. And it, so many of our programs prevent people from ever rising to their potential. And so it’s like, we’re, we’re getting eaten alive on the Republican side because of people on the Democratic side, who absolutely have the same outcome desire that we have. They have a way different thought process on how to get there. And it’s like, I’ve been through it, gotten myself out, from work, by work, being the one who’s got to the Payment Processing Center earlier than anyone else, worked harder than anyone else, applied for jobs that came open within the company. Some of them I got, some of them I didn’t.

I worked my way up. I worked my way out of poverty. It can be done. I got my education. Wow, I did it. It was not easy. Becoming better is not easy, but it’s worthwhile. And I wanted to be in — a better example for my children. So being in politics, it was like, I didn’t want to feel so out of place because clearly I don’t have that training. I don’t have that, but it’s like, you just said that right? You know, and it’s oh, so it’s like my, my spirit, my heart wouldn’t let me not speak up, wouldn’t let me not get in the fight. And I’ve never been someone to shy from a fight. I wish we didn’t have to have them, but I’m scrappy. So if we have to go, let’s go. … That is how my life has been in the Missouri legislature.

EJ: Well, you know, to my knowledge, the only member of Congress here in D.C. that has been homeless is from your state, and I believe it’s — I believe it’s Cori Bush. And I’ve interviewed Cori Bush before. And something that’s interesting to me hearing your story is that the only people the media wants to talk about, the only people who represent the working class, are the ones on the left. The media only wants to talk about leftists who have like working-class backgrounds. And J.D. Vance obviously had a huge breakthrough with “Hillbilly Elegy.” But it’s like the reason there’s so much push for as you say those programs that can actually depress mobility is because nobody tells the stories from the perspective of people who’ve escaped. You know, these, these difficult backgrounds, have lived working class lives, and believe in conservative ideas. And it’s not lack of, I imagine, from your perspective, plenty of people like you exist, you have seen the right with these programs.

HTR: They’re just not in politics. And so and it really brings me to a thought or instance that happened. So we were talking about putting in a picture ID on the food stamps, cards, you know, the EBT cards, what they’re called now, so their credit card to put the picture of the person. And we had folks on the left who said, “people are not selling their food stamps. This is ridiculous. This is a non-problem that you’re trying to find a solution for.” And I’m like, I mean, I still have family that does it out in the Save-A-Lot, parking lot, and so don’t tell me it ain’t happening. I grew up with it happening at 50 cents on the dollar. That’s the price that it goes for. And absolutely, it’s being done right now. It’s like, nobody could refute that. I have the evidence. I am the evidence. And so, we need more people who will, one, speak up. Because like you said, more people have seen this. I’m not afraid of what they had to say about me. Fine, talk about me. I don’t care. This is my true life. This is where I’ve been. But we have to have policies that fix that, right? And that’s what we should all be shooting for, not arguing about whether something is happening or not. It’s happening. So let’s find a great solution.

EJ: And yeah, right. The people who speak about, that it’s different if they’re sort of suit-clad Republican businessmen, as opposed to people who have lived it and do live it and understand it. Do you — do you think or could you speak to, because here in D.C., there’s all kinds of talk about how the Republican Party can be more of a working-class party and can, can help people with upward mobility and restore upward mobility, you know, in ways that you know, you have stagnant wages, you have all of these different economic troubles. And some of these ideas are good, and some of them are bad. And some of them, for instance, seem to resemble programs that have failed — programs without work requirements, programs without marriage requirements.

So if you were speaking to, let’s say, somebody here in D.C., who’s trying to come up with a policy, how important are these, like traditional conservative ideas about work and about marriage to upward mobility when you’re making, you know, big bureaucratic federal state programs? How important is it to have those in there? Maybe it’s not again, leading question, what’s your take up?

HTR: No, work requirements are very important. And I would first say, you have to come down off your high horse. And that’s been a lot of the problems on our side of the party. We don’t — we have so many people that are, I don’t know if they’re the ones making the most noise, or if they’re the ones getting the most media attention, but they stick to these banner issues that kind of get them on the media, that kind of you know, “they’re the hard hitters. They’re the this, they’re that that.” And it’s like, really, what have we, you know, what we need are people who don’t mind really digging in and saying, OK, in this state it’s worked. This program has worked this one has. And so we need to get rid of that. And we need to do this.

Look, when it comes to work requirements, and welfare, and our state, we changed it to a three-year TANF, you can be on TANF for three years. During that three years, you have to be in a technical program or some form of educational program, or volunteering. And volunteering opens doors. You’re volunteering and you’re the hardest worker in that room, somebody’s going to hire you. As an employer myself, somebody wants to want to hire you. So you, you have to have the benchmark to help people because we’re talking about, and I’ll just say people who grew up like me, no one taught me how to do a resume. No one taught me what I was supposed to look like when I showed up in an interview.

All these things, I learned those things by watching others, when I got that job in the mailroom of the corporate office of a cable company. I started mimicking the professional women that I saw there working there. And so you have to get — you have to help people get into a place that they understand what will help them to get that job work or to get that, and it is so empowering. The first time I bought Rachel a Happy Meal with my own money. I had money left that I had leftover out of my check, it was, it was the most empowering feeling, I wanted more of that so much more of that. And that’s what we have to help people get to, I don’t want to know the number, our state makes me crazy, because they’ll want to give us that number of people who have gotten off of welfare at that three-year mark. And it’s like, don’t count me the number of people we’ve dumped off this system. Tell me how many people have hit the benchmark, how many have gotten a technical degree, how many have gotten into higher education in some form, or how many have gotten employment. Those are the things that matter. That’s what affects upward mobility. That’s what affects breaking the poverty cycle, is when those kids in that home now get to see mama go into work, get dressed, dropping him at school, or daycare, go into work, and being proud of herself. That’s what changes things.

EJ: How has, and it’s very different, and it’s interesting that it’s very different now, the advent of social media in different technologies that are incredible time sucks, are completely addictive, and intentionally addictive. How has that affected people’s, you know — when you can connect with folks digitally, and you technically really don’t have to leave your house or your apartment, it creates a sort of synthetic experience, and it’s almost like it replaces it, but it doesn’t really replace it. So in communities where as we’re just talking, the social ties have been severed, and they’re frayed, and you have emptier church pews, you have those dried up bowling leagues, you have your PTA meetings, now it’s different. Now the PTA meetings are packed, but that’s for a different reason. When you have these, these, you know, civil society kind of driving a drying up, how has social media and technology then come in video games even and sort of tried to take the place in a — in a way that you never really can replace?

HTR: Honestly, I haven’t studied it much. But the articles that I have read are just staggering, when it comes to the disconnect. And when it comes to that — that missing out on that social connection, and learning how to just interact socially face to face.

And you can see that when you go into a restaurant, and you see everyone around the table with their phones in their hand. That’s what kids are seeing and kids are doing the same thing. It’s— it’s incredibly difficult. On the political side, it’s incredibly frustrating, because I see a lot of my colleagues who just play to whoever’s angry on social media, right? … It gets them likes. It gets them more energy towards themselves or whatever. And it’s like, you’re literally lying and harming society by that being the way that you legislate. And it’s so frustrating. But social media has absolutely affected our family fabric, but then it has also affected the policy side in such a negative way.

EJ: I’m curious as to how, and this is more of a national-focused interview than Missouri. I’m sorry. It’s — I’m from Wisconsin, where we, I guess we’re rival beer makers. But I was wondering the effect that Donald Trump has had on the Republican Party, from your perspective. What has that done? Has that been a positive shift? Has he brought people — I think a lot of the times we don’t think about all the people who, who don’t vote, who then did go out and vote for Donald Trump. It’s not just that they were voting Democrat. It’s frankly that they weren’t voting. They weren’t even political. Can you talk about how you’ve seen, you know, what has the effect of Donald Trump been not just on the Republican Party, but in politics from the, that’s in working-class communities?

HTR: I think it’s been a very positive effect. I — like I said, I never paid attention to politics, right? Growing up, I was in survival mode, raising my kids, being a 16-year-old with a baby on my hip. I didn’t know the president was. I needed to figure out where we were sleeping. I needed to figure out things that were important. Politics was not important to me at that time. I think it is absolutely made our communities, made our working class more aware more — more aware of seeing what I saw, like when I walked in the capitol for the first time and listened to those debates and was like, “you’ve got to be kidding me.” These are the people who are deciding for [inaudible], my taxes? I think that it has given them that “aha moment” that I had walking into the Capitol and seeing it face to face. And I think that’s incredibly important. Because it made me aware. It made me get engaged. It made me want to be a part of change — to realize that I could be a part of changing. Because before I never — it was like that was for the upper class. I didn’t know anything about that. And I think that it has really helped draw people in, who never knew that they truly do have a voice. And we need to hear it.

EJ: A lot of people, especially here in D.C., do play the same game that they’ve been playing for since 2015. But now it’s, you know, Jan. 6, and the election, they say, “How could anybody support Donald Trump, after all of this, you know, all of these clear flaws and all of these different things that he’s done? How could anybody support Donald Trump?” But in fact, a huge swath of the country continues to do that. And I’m sure it’s a big chunk of your constituents as well. What would you tell people who continue and have for the last seven years struggled to understand why it is that all of their controversies that they think, “this is it, this is the end of Donald Trump.” Why are they never the end of Donald Trump?

HTR: If they would stop lying to us first. That would, you know, I mean, that’s the thing is that when you can’t try, because how many things have we seen, come out and be absolutely incorrect. And so, when folks in my district watch the national media and see them hitting on Donald Trump, the first thing they say is, “Well, that’s another lie.”

EJ: Right.

HTR: It’s not something that we don’t trust the national media because we’ve been lied to. Case in point: the kids that went, and — for the pro-life march a few years ago.

EJ: Yes, Covington Catholic, right?

HTR: Covington Catholic — one of my good friends, my trainer, her son was on that trip, that school. And I knew from her that those kids were not being disrespectful. I knew that that was the media taking a snapshot of a teenage white boy from Mid-America, saying that he was being disrespectful when he was trying to stand there and just be respectful and not — not knowing what to do when an adult man was in his face. So issues like that is why we don’t trust the national media. …

The whole thing with the dossier, all of that, what has been shown to us, right? So what we see, his policies at the gas pump, were a lot easier to swallow. Go into the grocery store now, we’re paying at least 25 percent more, sometimes more than that. And people are hurting. And that’s what matters to us. What the economy — what we’re paying for, I live in one of the poorest districts. My district — they feel it when the gas goes up 30 cents a gallon. I mean, when that mama is putting in — I was that mama pulling up and putting $2.50 into my gas tank, because that’s all I had. What can she get on that now, right? When you have to go to the laundromat to do your clothes, and you’re using your gas masks to wash your clothes, I mean, those are the things that we’re feeling, and Donald Trump had our back.

EJ: And again, that perspective, from the working class on the left, it’s sort of obvious, right? Like, it has plenty of airtime in the national media. But from the right, you get absolutely nothing because if anybody dares to open their mouth, they’re called any number of horrible, horrible names. It’s unbelievable.

Well, before we wrap up, I also wanted to ask about men who play obviously a large role in your book. And, you know, there’s — there are real problems, I think with the culture that our men are growing up in right now. And I’m curious, Holly, what you think, can be done what you think needs to happen to create, you know, a more healthy culture for both men and women, but especially men in a world where women are now outpacing them in terms of earning college degrees, and where work has changed so much, so that a lot of men who did get their college degrees are not in jobs that are using college degrees. And women are out-earning them, and this creates all kinds of different dynamics when it comes to marriage, when it comes to dating, when it comes to children. What do you see when it comes to the culture that — that men are raised in and that they’re living in? What do you think needs to change?

HTR: I don’t know. That’s such an incredible question. I have two sons. One is 30, and one is 25. My 30-year-old went to work for our family business at 15. You know, he’s been in the family business forever and didn’t go on to higher education. He went straight into working for us. My 25-year-old went to college — brilliant guy, did the fraternity, did all the things, you know, and, and he now is editor of the heartland her.com, which is a political online news outlet in Kansas City, and does a wonderful job.

But I’ve raised my boys to be respectful, and to treat others as you would have them. Treat your view. And I think that Christianity, whether — whether you’re a Christian or not, certainly you can agree with treating others, the way that you wish to be treated yourself is what’s right. And so in a marriage, whether the wife is making more than the husband, that shouldn’t be a factor. It shouldn’t be a factor when the man is making more. You’re both going out there and working, whether one is working in the home, and one is working out in a job or vice versa, or both are. I mean, marriage is hard enough, you know? You don’t need to add those kinds of issues to it. But to me, I mean, God is the answer. I hate that so much of our Christianity has been removed from our school. Certainly, America was built on Christian principles. And I mean, that I see that as a problem. …

EJ: We chuckled earlier about the PTA meetings. But I also wonder, you know, your constituents, your community, how are — how do they react to the culture war? How animating is that for voters, because it’s a — it seems to me, it’s huge when you have schools teaching completely anti-American, anti-patriotic things, whether you’re in San Francisco, or rural Missouri, these things really are upsetting to voters, what it’s what you’re teaching in terms of what constitutes a man, what constitutes a woman, what you’re teaching, when it comes to the history of the country. These things actually really do make a huge difference electorally, and so as you were saying, it’s a big deal, what people are paying at the pump. That’s something that will, that will bring people to a candidate like Donald Trump. But it seems to me also some of these cultural issues can be as important to people, if not more, when they’re making that decision about, “do I vote and who do I vote for?”

HTR: Absolutely. And, you know, in my area, I’m in a deep red area. And we’ve not had some of the trouble in our schools that some of the others across the state have had. We’ve not had CRT in our schools. Now, years ago, we did have the Common Core. And we had many people show up at our school board meeting. And it was quite contentious. But it was — it got resolved because of that, right? And so I’m blessed in a — on the side of, my schools really aren’t going through some of that. We’re not — look, and when it comes to men playing in women’s sports, like there’s just so much with that, that, that has nothing to do with my, my friends that are, homosexual or you know? It is — you are removing a female’s capacity to get a scholarship.

EJ: Exactly.

HTR: You are removing women’s sports. You are not qualified. I’m slow. I would never be allowed on the track team, you know? So it’s — you are not qualified, but little by little everyone tries to — not everyone, many on both sides try to make things a political war when it doesn’t have to be. It’s like you’re not qualified. OK? No, that’s — that’s not okay. We’re not going to remove women sports to fit people who want to participate. Pick another thing that — you’re not qualified.

When it comes to CRT? Absolutely, we need to teach the history of America. But we cannot teach our children that they are racist because they’re white. That’s not OK. I have a mixed-race family. That’s not OK. And thank goodness, we’re not hearing about that in my district right now.

EJ: That is wonderful. You know, wherever you are in the country, with what you’re watching from Hollywood, what you’re watching on the news, it’s — it’s all been sort of poisoned by a very negative ideology in Hollywood. We talked right at the beginning about hope. You mentioned how important hope is, and to empowering everyone. So I want to sort of close on that question. Empowering people and giving them that sense of perseverance and purpose. I want to close on this question just to you. Are you optimistic? Are you hopeful about the future of the country, as we’ve been discussing all of the sort of many, many problems that are ailing us right now? Are you optimistic about the future?

HTR: I am, I really am. I think that — I think that we have and, and as we talked about with Donald Trump, I think that we have more awareness of how politics really does affect our lives. And so we have more people getting engaged. Our kids coming out of high school, they’re more engaged. And, and you know what, I mean, I would have considered myself a Democrat, if you probably would have asked me as a teenager because I knew my mother had told me she voted for Jimmy Carter. That was really all of the electoral understanding that I’d ever had. And my mentality was that Democrats help poor people like me, right?

EJ: Right.

HTR: But the more, you know, by the time I was 19, working my tail off, and — hey, I figured it out. You raise, you raise the minimum wage, my groceries are going up. You know, I mean, I knew there was a correlation. And — and our kids are smart, and they’re seeing that also. And whether it was the Trump way, or whatever it was. But I think that it — I think that it’s absolutely going to be positive and bringing more hope and more changes for the good in the future. I think more people are getting it.

EJ: Holly Thompson Rehder, thank you so much. It’s been an absolute pleasure. And thank you for your candor discussing your past. It’s just a wonderful conversation that I hope will — will be interesting to our listeners. I know it will be.

HTR: I appreciate you so much. And I’ve enjoyed it. I’ve enjoyed talking about all the different topics.

EJ: Yeah, it was a wide array and well, we’ll have to do it again. The book is called “Cinder Girl.” Oh, we didn’t even get to talk about the title. That’s from “Ever After,” right? It’s from the Drew Barrymore movie?

HTR: It is, it is my favorite movie. She saves herself. A prince doesn’t come swoop her up.

EJ: Oh, that’s wonderful. Well, now it’s — it’ll be easier for the audience to remember. The book is called “Cinder Girl: Growing Up on America’s Fringe.” It is out now. Make sure to grab a copy and read it. Holly, thank you again for your time.

Sophia Corso contributed to this article.