The flagship of the Russian Black Sea fleet, the missile cruiser Moskva, sunk on Thursday after large explosions shook the ship following what the Ukrainians claim was a missile attack on Wednesday. The Russians say the cause of the fire onboard the evacuated warship is under investigation.

According to The Daily Mail, the Ukrainians used several Turkish-built Bayraktar drones to distract the Moskva’s air defense systems before striking the ship with two domestically-built Neptune anti-ship cruise missiles. If true, this displays a high degree of battlefield coordination that the Ukrainians have used to largely thwart the invasion launched by their much larger neighbor.

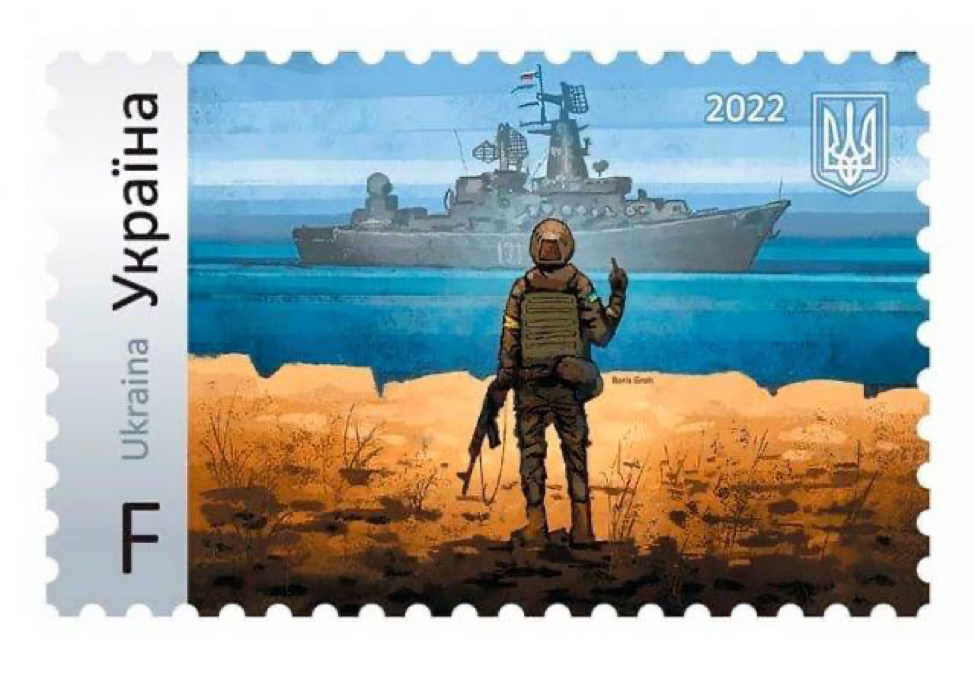

For the Ukrainians, the strike on the Moskva would represent a helping of revenge. The ship was the lead warship in Russia’s opening moves on Snake Island in the Black Sea, an action featured on a new Ukrainian postage stamp.

From a practical perspective, the loss of the Moskva is significant, not only because it served as the Russian flagship, coordinating the Black Sea fleet, but also because the ship’s significant anti-air and anti-missile capabilities provided an air defense umbrella for the smaller ships around it. Consequently, the Russian amphibious threat to Odessa has virtually been eliminated, allowing Ukraine to redeploy forces assigned to the defense of that key port city to the battle to retake Kherson, about 90 miles to the east along the Black Sea coast.

The big enemy of warships through the centuries has been fire. Until the age of steel, fire could burn a ship down to the waterline. With the advent of gunpowder, the additional danger of explosives onboard made fire even a greater threat.

With the age of iron and steel, ship designers did what they could to protect vital parts of the ship, such as the engine room, command and control areas, and fuel and ammunition storage bunkers. But as missiles replaced guns, naval architecture went the other direction, largely discarding armor protection in favor of offensive punch and active defensive systems, such as radar-confusing chaff, electronic countermeasures, and anti-missile systems — both surface-to-air missiles and close-in weapon systems (CIWS).

Moskva had plenty of the latter but for some reason (training or maintenance issues with the targeting chain — radar to crew to weapon system) they proved ineffective against what should have been an easy task: shooting down large, sub-sonic cruise missiles.

As a result, a missile with a relatively small 330-lb. warhead can knock a 12,490-ton ship out of commission when that warhead ignites the large amounts of missile propellant and explosives on the target ship — it’s the secondary explosion that’s the bigger problem. Much like all those photos we’ve seen of Russian tanks with their turrets blown off and flung many yards away, when the small antitank missile warhead penetrates the turret and detonates the tank gun rounds stored onboard.

The loss of a flagship during war can be devasting to a navy’s pride as well as national morale. This is further complicated by the fact that the ship was named for Russia’s capital.

This threat so vexed Adolf Hitler during World War II that he ordered the renaming of the heavy cruiser KMS Deutschland to Lützow in early 1940, recognizing that the loss of a warship named for the nation itself would be a devastating propaganda victory. This cautionary move was validated when, only three months later, a sister ship of the newly renamed Lützow, the KMS Blücher, was sunk by gunfire and torpedoes from Norwegian coastal defense batteries on April 9, 1940.

Blücher was the flagship of the German operation. Lützow was also damaged and forced to withdraw in the same battle. The loss of these German ships in the battle delayed Germany’s Norway conquest timetable, allowing the Norwegian royal family to escape and lead a government in exile. Blücher’s displacement was 18,500-tons, about half again as large as Moskva.

Some 42 years after the sinking of Blücher, a nuclear-powered Royal Navy attack submarine hit the Argentinian cruiser ARA General Belgrano with two torpedoes May 2, 1982, during the Falklands War. The General Belgrano, formerly, the USS Phoenix, a U.S. Navy light cruiser, sank with the loss of 323 of the ship’s 1,100 crew members. General Belgrano displaced 12,242-tons when loaded for battle, slightly smaller than Moskva.

Thus, the Ukrainian attack on Moskva, coming almost 40 years later, represents the largest warship sunk during wartime by hostile action since WWII — and much like the Norwegian sinking of Blücher, by a nation with effectively no navy.