I don’t often think about evolution, but I recently found myself doing so under the warm, cerulean waters of Sharks Cove on the North Shore of Oahu. I was snorkeling, taking in the tropical fish schooling around me. I thought, how did their diverse and extravagant beauty come to exist? If natural selection is the engine that created the living world, what is the reason behind this opulence? Why does beauty even exist in the first place?

The genius of evolution is its brutal pragmatism; do whatever is needed to pass your genes onto the next generation in the fastest, most efficient, enduring way possible. It knows nothing else. As such, it should be inherently prejudiced against not only complex beauty, but any conspicuous beauty at all.

So why the Moorish Idols and their elegant neighbors at Sharks Cove? If natural selection reined, they would see the runaway genetic success and durability of the common guppy and ask, “Why am I knocking myself out trying to maintain this extravagantly conspicuous design when I could be that guy?”

Mr. Guppy is a child’s starter fish for a reason. He lives years in a tiny, dirty fishbowl needing minimal attention. Algae thrives there. The same is true of the common finch over the peacock, or the dandelion and the orchid. One is common, while the other is rare for a reason.

In survival of the fittest, the fittest is the least complex and needy — Occam’s razor applied to living things. Extravagant, superfluous beauty is not evolution’s friend. Ironically, isn’t the environmental movement built on this very fact? Some species are less adaptive to changing environments, man-made or not, and rightly require protection.

Thus, beauty is one of evolution’s most serious and persistent problems. Its adherents have no good answer for it, and not for want of trying.

An Attempt to Explain Beauty

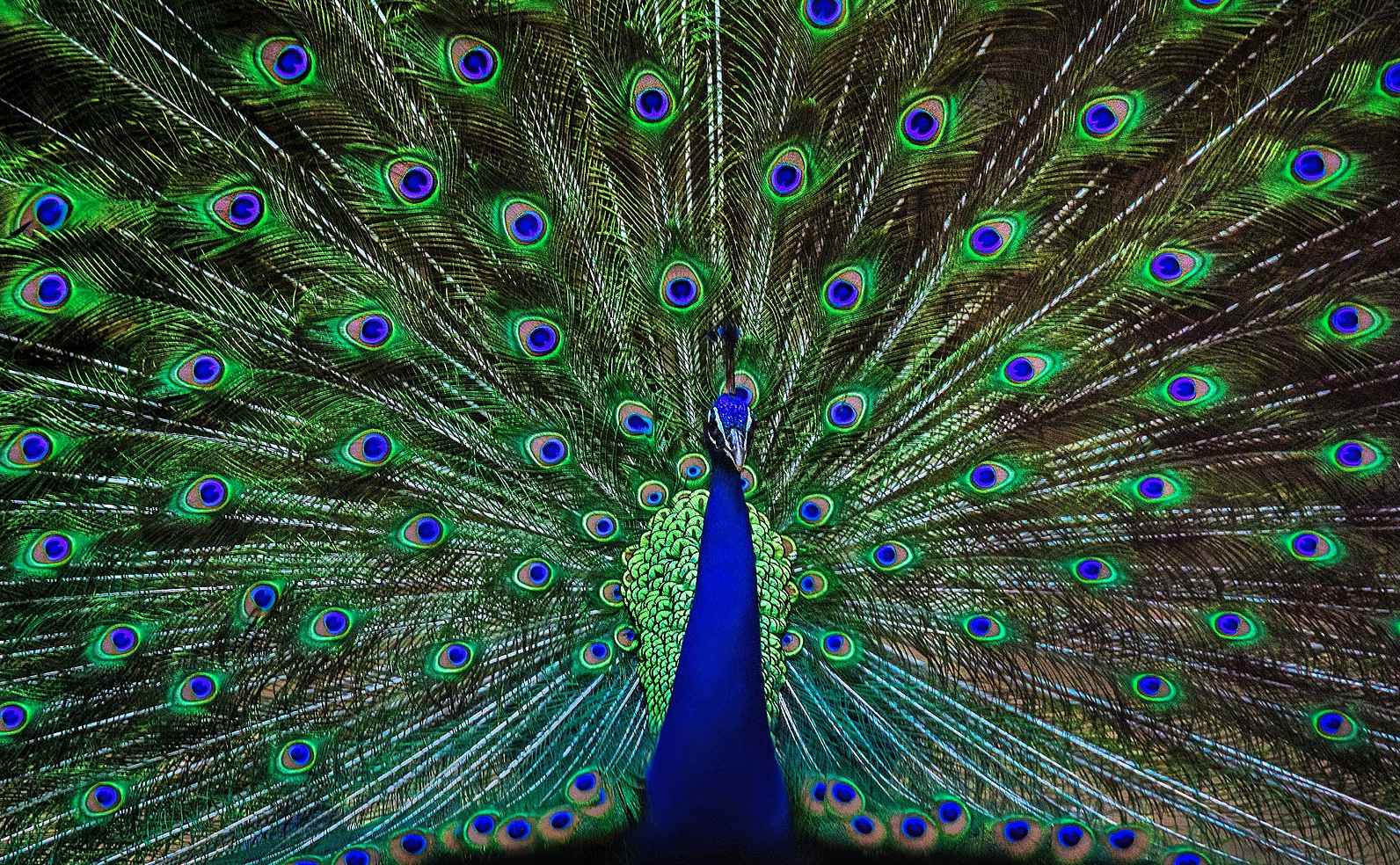

The two men who simultaneously developed the theory of natural selection, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, were profoundly burdened by the problem of beauty. Darwin confessed to a friend, “The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!”

Wallace held that a peacock’s raiment was more than unnecessary under natural selection; it was a detriment. He confessed the “excessive length or abundance of plumes begins to be injurious to the bearer of them.” Darwin and Wallace both worked tirelessly but unsuccessfully to come up with a sufficient explanation for beauty. Both disagreed passionately with the other’s answer.

Darwin proposed natural selection was not the only phenomenon at work here and developed the theory of sexual selection. The prettier you are, the more action you get. Wallace rejected this theory, writing in 1878, “The only way in which we can account for the observed facts [of conspicuous beauty] is by supposing that colour and ornament are strictly correlated with health, vigor, and general fitness to survive.”

Darwin’s theory was about attraction, Wallace’s about longevity. Biologists generally find neither convincing.

Sexual selection raises a very serious secondary problem: the complex beauty of binary mating. The asexuality of the mudworm or hydra is simple and highly efficient. Why remove that ability from the individual and require complex coupling? Natural selection is not inclined to say, “Let’s make this exponentially more difficult,” which finding, competing for, wooing, and impregnating a mate certainly is.

The beauty problem is no more solved today than it was then. In fact, it is such a live question surrounded by passionate disagreement that a recent publishing event created quite a controversial splash. First was “The Evolution of Beauty” by Yale University’s distinguished Richard O. Prum. Following was Michael J. Ryan’s “A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction” published by Princeton University Press. Ryan’s attention is on what attracts potential mates and why.

Both books received a great deal of attention yet kicked up more disagreeable dust than agreement. Prum told The New York Times, “I don’t know anybody who actually agrees with me. … Even my own students aren’t there yet.” He holds that the genetic advantages of choosing a beautiful mate are negligible, as biological benefits are themselves rare while superfluous beauty is “nearly ubiquitous.” Research supports the rarity of beauty’s practical selective benefits. Prum admits the scorn from his academic peers is painful.

The problem forced both authors to posit a very radical new angle on natural selection. As one reviewer notes, the two hold that “evolution is not a purely utilitarian process.” Animals likely favor beauty “in form, color and behavioral displays … for its own sake” and thus it might “be of no practical use whatever.” Some things serving no practical purpose can perhaps arise through natural selection, but it is beyond reason that the tremendously complex beauty of this guy or the one pictured below would come to be.

Prum’s theory is captured in his simple phrase “beauty happens,” just as he tells us “stuff happens.” The answer from evolutionists that beauty simply exists is just stunning when they have long said with great pride and assurance that natural selection can explain what we find in all living things.

But this is at least the honest admission that beauty serves no evolutionary purpose. All they can tell us is that beauty happens, which we knew coming in the door.

Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder

Over and against Prum and Ryan, most biologists and armchair evolutionists continue to assume, along with Darwin and Wallace, that beauty serves to attract potential mates. The problem here is human prejudice, assuming that what is beautiful to our eyes must also be beautiful to an animal’s mate.

Couldn’t the iridescent peacock just as well appear garish to the peahen, while Mr. Blobfish cannot imagine anyone more lovely than Ms. Blobfish? It’s just as likely as it isn’t. If reproduction is driven by beauty, ugliness would be its speed bump. This is clearly not the case.

It seems more reasonable, as Wallace believed, that extravagant beauty is likely to eject creatures from the gene pool. It requires more energy to develop and maintain and makes one highly conspicuous and attractive to predators.

The rosy maple moth is the precise opposite of Darwin’s famous camouflage peppered moth we all learned about in school. Hunger being a stronger and more constant need than mating makes Ms. Maple Moth and her other beautiful friends more attractive to predators than mates.

Finally, if extravagant beauty makes one more attractive to potential mates, it also makes them more vulnerable to the jealous violence of lesser peers. Natural selection is to nature what socialism is to the economy. It does not favor the ambitious or flamboyant, but the one who keeps his head down and doesn’t ask for much.

The stunning beauty of living things is one of the most wonderful treasures in life. While the rest of us can’t imagine life without it, its absence would certainly make life easier for the evolutionists. They will just have to accept their beautiful plight.