In presidential election years, a sure sign of spring — along with crocuses, sunshine after 7 p.m., and Coach K appearing in commercials — is a new round of primaries every Tuesday.

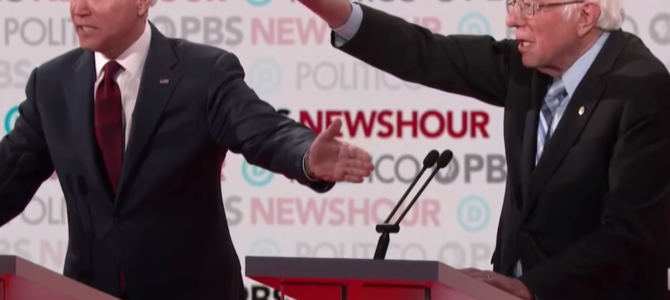

This week isn’t quite Super Tuesday, but it features six states voting, from the Pacific Northwest to the Midwest to the Deep South. Michigan, which has the most delegates at stake and where Bernie Sanders pulled an upset in 2016, is likely to get the most press attention, but Joe Biden might pull off an unexpected victory in the day’s second-largest prize: the state of Washington.

Will Biden Keep His Lead Over Sanders?

In addition to the rapid consolidation of center-left voters behind Biden and the media’s aggressive anti-Sanders campaign, two factors have prevented the democratic socialist from keeping his front-runner status through Super Tuesday. First, as I pointed out last week, Sanders is not getting the same percentage of voters he got in 2016. This drop-off might be expected in a multi-candidate field, but it has continued as the race has evolved into a two-man contest between Sanders and Biden.

Second is the decline of caucuses and their replacement with primaries. In 2016, 14 states held caucuses; Sanders carried all but two (Iowa and Nevada). This year, only three states are holding them, a number that may fall even further in the future after the debacle in Iowa.

These factors were both present on Super Tuesday. Sanders failed to reach his 2016 percentage of the vote in all 14 states, and four of his six biggest declines came in states that switched from holding a caucus to holding a primary. (All election data are from the Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections as of March 8.)

*Held caucus in 2016 and primary in 2020.

Washington provides a near-unique example of Sanders’s comparative performance in caucuses and primaries. It held a caucus, which chose the delegates, in late March 2016, and a non-binding “beauty contest” primary two months later.

Sanders cruised in the caucus, winning more than 70 percent of the vote, but Hillary Clinton won the primary by a 52-48 percent margin. (Nebraska, the only other state with both a caucus and a non-binding primary, had a similar split.) The county-level comparison between the caucus and primary, and the primary results, are mapped below.

As you can see, the gap between the caucus and primary results was fairly evenly distributed across the state. In the primary, Clinton’s strongest county was King County, which includes Seattle and its immediate suburbs. Sanders did better in rural areas, particularly along the Canadian border.

This might be the biggest red flag for the democratic socialist and the greatest opportunity for Biden. In the primaries so far, Sanders has seen the largest declines from his 2016 percentages in predominantly white, rural areas, a description fitting the parts of Washington state where he fared best in 2016.

Sanders will need to gain ground in Seattle, particularly among voters who previously supported Elizabeth Warren, to make up for potential losses there. Recent polling from Data for Progress and King 5 TV (the latter taken before Warren dropped out) show Biden taking a narrow lead.

What to Watch in Washington

On the surface, Washington resembles the two states where Biden had the most surprising victories on Super Tuesday, Massachusetts and Minnesota. All three states are predominantly white and northern. They all have a reputation for liberalism and a medium-sized population dominated by a single large urban area.

In Massachusetts, however, the progressive vote was split between Sanders and Warren, who was trying to mount a last stand in her home state. Minnesota was expected to be a showdown between Sanders and state native Amy Klobuchar, but Klobuchar dropped out and threw her support to Biden a couple days before the primary.

No similar home-state candidate dynamic exists in Washington. Gov. Jay Inslee briefly ran for president, but he dropped out months ago and has not yet endorsed Sanders or Biden. While the coronavirus has hit Seattle harder than any other American city so far, it should have a minimal effect on the election since most voting in Washington is done by mail.

As the votes come in, three areas bear watching. The first is King County, where Sanders will likely need to improve on his 2016 showing to win statewide. The second includes Spokane County and Thurston County, where Olympia is located. Sanders carried both counties narrowly in the 2016 primary, and maintaining them would be a sign that he is holding his own in Washington’s smaller urban areas. The third is the rural areas of the Olympic Peninsula and southwestern Washington, a traditionally Democratic area where five counties flipped from Barack Obama in 2012 to Trump in 2016.

Of those five counties, four had not voted for a Republican presidential candidate since at least 1984. These include Pacific County, which hadn’t voted Republican since 1952, and Grays Harbor County, which hadn’t voted Republican since 1928. Clinton and Sanders split this area in 2016, but if the pattern holds of Sanders losing support in traditionally Democratic areas that have trended Republican, Biden could do well there.

So far, most coverage of this week’s primaries has focused on whether Biden can sweep Mississippi or whether Sanders can repeat his surprise victory in Michigan. Once the votes are in, though, we may find that the most decisive win for Biden came on the West Coast.