“Richard Jewell” looked like a rousing, can’t-miss crowd-pleaser from its excellent trailer, which shows did-the-right-thing security guard Richard Jewell being ground down by intimidating FBI interrogators and persecuted by rabid reporters. How could it possibly miss, with a wronged good guy facing off against what his lawyer refers to in the movie as the two most powerful forces in the world: the federal government and the news media?

Sadly, the film somehow manages to tell this real-life David-versus-Goliath tale with such bland restraint that it actually becomes boring, in addition to looking TV-movie cheap. At two hours and 11 minutes, it feels tediously long. That’s not as in “sympathetically experiencing the hellish duration of the main character’s Kafka-esque torment” long, but as in repetitive, flat, and lacking dramatic tension.

I know, I know. From the ads, this looks like a guaranteed Best Picture nominee for director Clint Eastwood. But like the titillating trailers for fake movies that appeared in Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez’s “Grindhouse,” previews alone can be preferable to products that don’t live up to their promise. (Rodriguez himself later proved this when he made a full-length version of what started out as a phony trailer for “Machete.”)

‘Richard Jewell’ Turns Potential Strengths into Weaknesses

Elements that should have been the movie’s strengths — including an interesting real-life cast and a compelling narrative — are squandered. Richard Jewell, a wannabe cop with a history of job-related complaints and quirky character flaws, reports a suspicious package at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics that turns out to be a bomb. At first celebrated and praised, he is later vilified by the press after being named the FBI’s primary suspect for the explosion, which killed two people and injured more than 100.

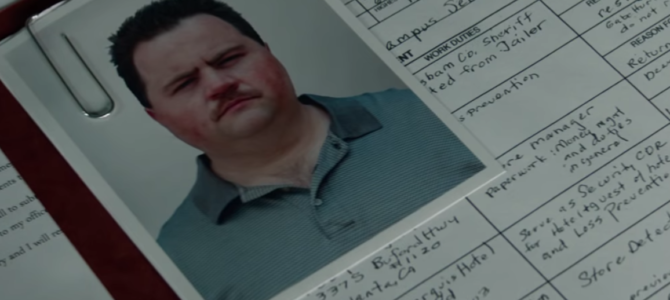

Paul Walter Hauser (who played Tonya Harding’s bodyguard in “I, Tonya”) portrays Jewell as a cartoonishly accommodating Barney Fife doofus, instead of as the more intriguingly complex eccentric he apparently was. Although we see Jewell get fired from a college security job for nutty, beyond-his-duties transgressions, and hear that he was required to seek psychological counseling at another job, the movie prefers to paint him as a simpleton saint instead of a potentially genuine red-flag threat.

Sam Rockwell does a good job of portraying Jewell’s exasperated attorney Watson Bryant, who can’t get Jewell to keep his mouth shut despite repeated attempts to silence his would-be helpful outbursts. Movie-wise, it becomes odd that Bryant and Jewell seem to spend nearly every waking hour together during the entire ordeal, with no explanation as to how Jewell possibly could afford all those implied billing hours. (The words “pro bono” are never uttered.) The real Jewell eventually added to his legal team, but Bryant is the only lawyer we see here.

Jon Hamm is excellent as the coolly deceitful Tom Shaw, a fictional FBI investigator who subjects Jewell to various insulting and borderline illegal indignities Jewell actually endured from real agents. The problem is that while tactics such as deceptively trying to avoid reading Jewell his Miranda rights are clearly wrong, making Shaw a pure villain trivializes the fact that Jewell really did fit several profiler markers that raised suspicions about him.

When agents search the apartment Jewell shares with his mother, the number and variety of firearms Jewell has laid out for them on his bed are definitely eyebrow-raising. (In answer to an earlier question from Watson about whether he has any guns in the house, Jewell replies, “Yeah. We’re in Georgia.”) Kathy Bates stews and frets as Jewell’s mother, Bobi, who resents having her Tupperware and vacuum cleaner seized by the FBI, and eventually retreats from the living room for what feels like a contractually obligated crying jag.

The Film Sexes Up Reporter Kathy Scruggs

The movie’s most problematic character is Atlanta Journal-Constitution newspaper reporter Kathy Scruggs (Olivia Wilde), who is portrayed as obnoxiously arrogant, amorally cynical, and mercenarily slutty. So flagrantly theatrical and vulgarly vampy that she seems to have crashed in from a screwball sitcom, she actually prays out loud that when a bombing suspect is named he will turn out to be interesting.

Ironically, the way she gets Jewell’s name out of agent Shaw makes the movie appear as tainted by expedient dishonesty as everyone the movie condemns for defaming Jewell. With zero basis in fact, the screenplay by Billy Ray (“Captain Phillips”) shows Scruggs implying a sex-for-info transaction with Shaw at a bar. After he provides her Jewell’s name, Scruggs says, “You want to get a room or just go to my car?”

Although Scruggs is now dead, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution has called that portrayal of her “false,” “malicious,” and “extremely defamatory.” In addition to demanding a prominent disclaimer noting that the scene is fiction, the paper has threatened a defamation lawsuit against Warner Bros. for tarnishing its reputation. (A pre-release screening print of the film included only this standard Hollywood boilerplate at the end of the credits: “Dialogue and certain events and characters contained in the film were created for the purposes of dramatization.”)

Amusingly, Wilde has decried the “double standard” that people are singling out only her character for criticism, and not FBI agent Shaw as well. That desperate defense is like saying, “Yes, this scene was a complete lie — but we should get a pass because nobody is also blaming the behavior of the fictional character Scruggs seduces.”

The unforced error of contradicting the film’s entire message by unfairly sullying someone’s reputation to sex things up is as bizarre as Richard Nixon’s reelection committee bugging the Democrats, or the Patriots filming eight minutes of Bengals’ sideline footage. In the same way, the plot of “Richard Jewell” already had so much going for it that risking condemnation for such a trivial benefit seems self-destructively reckless.

The Film Ignores Jewell’s Important Media Lawsuits

The movie’s other incomprehensible flaw is that it makes no mention of the many successful lawsuits Jewell later filed against media outlets for coverage that made him look guilty. Considering that rush-to-judgment news organizations were responsible for so much of Jewell’s grief, not portraying the way some of them were taken to task feels anticlimactic. Even more puzzling is that the movie includes two real TV clips of anchor Tom Brokaw, one featuring his fateful “probably have enough evidence to arrest” pronouncement that would cost NBC an undisclosed settlement.

On the downside, Jewell’s suit against the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the first outlet to identify him as a suspect, dragged on for more than a decade. Ruling against Jewell’s estate in July 2011, the Georgia Court of Appeals concluded, “[B]ecause the articles in their entirety were substantially true at the time they were published — even though the investigators’ suspicions were ultimately deemed unfounded — they cannot form the basis of a defamation action.”

That information would have been an interesting endnote for the film. It also would serve as a warning for the next Richard Jewell, whose life the media can legally ruin through the technically accurate news that he is a suspect for a crime he didn’t commit.