The debate over trade and tariffs was quiet for a quarter-century. When Bill Clinton endorsed the North American Free Trade Agreement, he aligned his Democratic Party with the Republicans for free trade with the third world and quieted, he thought, one of the longest-running arguments in American history.

But history has its own ideas. Trade protection is a live debate again and the parties are divided against themselves and each other.

The free traders have a lot of top pundits on their side, but the arguments they choose are showing the rust of infrequent use. No one has needed to defend free trade with the developing world in a while, and now that they must, they are not doing a great job of it.

Protectionists have it even tougher, as they seem again and again to fall into the illogical traps their opponents set. There are three main false dichotomies in trade arguments that we should dispel.

1. Free Trade Versus No Trade

One false choice we have heard time and again from free traders is that America must choose between trade with the world and isolation. They present the world economy as one where only two states exist: free trade with everyone, or complete autarky and closure of the borders. This is a particularly common theme when discussing President Trump’s ideas on trade, conflating his border wall proposals—an idea about illegal immigration—with the tariffs he has imposed.

The comparison is foolish. Trump does not propose to stop all trade with China, only to impose a tariff on some goods from communist China. Likewise, he does not propose to tax illegal immigrants for entering the United States, he proposes to stop them or, failing that, to catch and deport them.

The two ideas are only similar in that they involve international borders. Beyond that, it is apples and oranges. Trump and those like him may ultimately desire to all stop illegal immigration, but they have no intention of stopping all foreign trade.

What would they like to do with trade? Manage it. For some good, from some countries, the Trump administration believes the United States should impose tariffs. That is, there should be some sort of government levy—usually expressed as a percentage of the value of the goods (an ad valorem tax). But nothing would stop those goods from entering the United States. A tariff imposes a cost on manufacturers, which is often passed on, at least in part, to the consumer. If consumers want to pay that, they can still buy the goods.

Tariffs raise revenue from foreign trade, but they do not stop it altogether. People in the free trade camp act as though any imposition on trade will kill it, but that has never been the case, even when tariffs were more common.

There were occasionally tariffs so high they were called “prohibitive,” but these were rare and, even when they were imposed, nothing prevented a determined buyer from importing the goods in question anyway. Tariffs alter trade—that is inevitable, and is usually the point of the tariff to begin with—but they do not destroy it. Protection is not isolation.

2. Trade War Versus Trade Peace

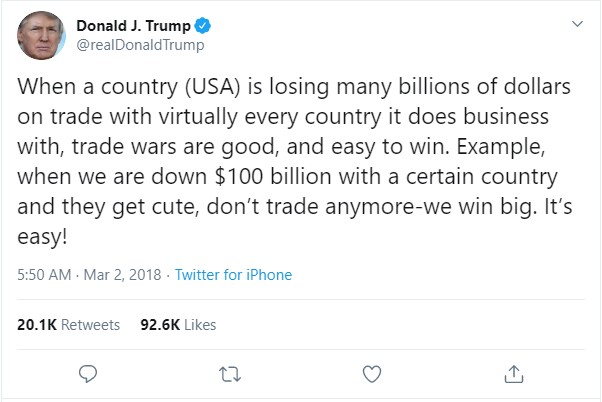

Trump has relished the idea of a trade war with China to an extent that discomforts the guardians of the former bipartisan consensus on trade. Indeed, his tweet from 2018 announcing tariffs on certain metals from China claimed that “trade wars are good, and easy to win.” No one in the free trade establishment liked that, and the line became a Twitter meme, rehashed every time any disruption of trade is noted in the news.

To say that trade wars are always good would be wrong, but it is also wrong to say that we must have the opposite—trade peace—at any price. Like actual wars, trade wars should not be permanent and never-ending, but neither should we always back down in the face of aggression. There is a difference between a war of choice and a war of necessity.

Free traders have the same view of trade war as Quakers do of real war: that it is never the answer. To remain a free and prosperous people, we should never rule out either real war or its metaphorical equivalent. When our nation is attacked militarily, as in Pearl Harbor or the World Trade Center, we are at war whether we wish it or not. The options then are not war versus peace, but victory versus surrender.

There was never any doubt in those scenarios that we would choose to fight and try to win. Whether war was the answer was irrelevant, because we weren’t being asked the question.

Trade wars are less destructive than real wars, and trade “attacks” can scarcely be compared to the carnage of military or terror attacks on the United States. But they are nonetheless attacks on our economy, and just because no one dies does not mean we should ignore the real-world consequences. The Quakers’ theories on war are like the free traders’ views on trade war: both can be easily avoided as long as everyone in the world believes in peace or free trade.

That’s true, but pointless. Enemies exist. Other nations are not satisfied with the status quo and will challenge us. Will we respond? When China manipulates its currency, subsidizes its exporters, dumps underpriced products, steals intellectual property, and generally flouts the rules of the World Trade Organization, then trade war is already upon us. The question is whether we will lie down or stand up.

3. ‘Tariffs Are Taxes’

Conservative free traders often attack protectionists in their ranks by saying that tariffs are taxes. This one is actually true—kind of. As money extracted by the government by force of law, a tariff falls into the same category as taxes, excises, and fees. The money gets paid to the state and the person paying it has no choice in the matter. In that, there can be no argument: tariffs are a kind of tax.

But taxes are also taxes, and far less easily avoided. The government needs some revenue, even small-government conservatives must agree, and taxes of one sort or another are how they get it. Currently, most taxes are on income. Unless you’re fantastically wealthy, you need some kind of income each year to survive. The government knows that, which is why they tax it. As long as the rates are not insanely high, people will not stop working just because their reward from work is diminished by taxation. They will do their best to avoid tax, legally or illegally, but they will always earn income because everyone not on public assistance must earn to live.

Other taxes are equally hard to avoid. Sales taxes are imposed in most states, so almost anything you buy requires you to pay a tax. It’s nearly impossible to avoid that one, too. Property taxes fall only on property owners in the first instance, but when property taxes go up renters should not be surprised that their rent tracks the increase. Gas taxes, road tolls, and others might be avoided, but only at the cost of a serious adjustment to one’s life.

Tariffs are more voluntary than that, even if they are still taxes. The consumer never pays them directly, and only pays them indirectly if he buys foreign goods (the cost of a tariff will be passed on to the consumer, the same as any other tax).

But this can be avoided by buying American, or even by buying from a country like Canada, with whom we have a free trade agreement, since tariffs can be selectively imposed by country. That argument ultimately applies to the whole supply chain, since even American products with foreign inputs may be affected by trade protection, but again, the solution is domestic production and consumption—that’s the whole point.

Free traders will say that tariffs drive up the prices of domestic products, too, and too high a tariff might ultimately do that. But one advantage of this free market domestic economy is that domestic producers will still compete with each other on price. Tariffs level the playing field against foreign competition, but they do not grant a domestic monopoly to any one manufacturer. As taxes go, they are less intrusive and less onerous than anything else we currently use to collect revenue for the government.

The debate over trade protection has reopened after a generation of politicians treated it like it was closed. The rust shows in these arguments. Both sides should take some time to sharpen their ideas and between them figure out the right way to strengthen American jobs.