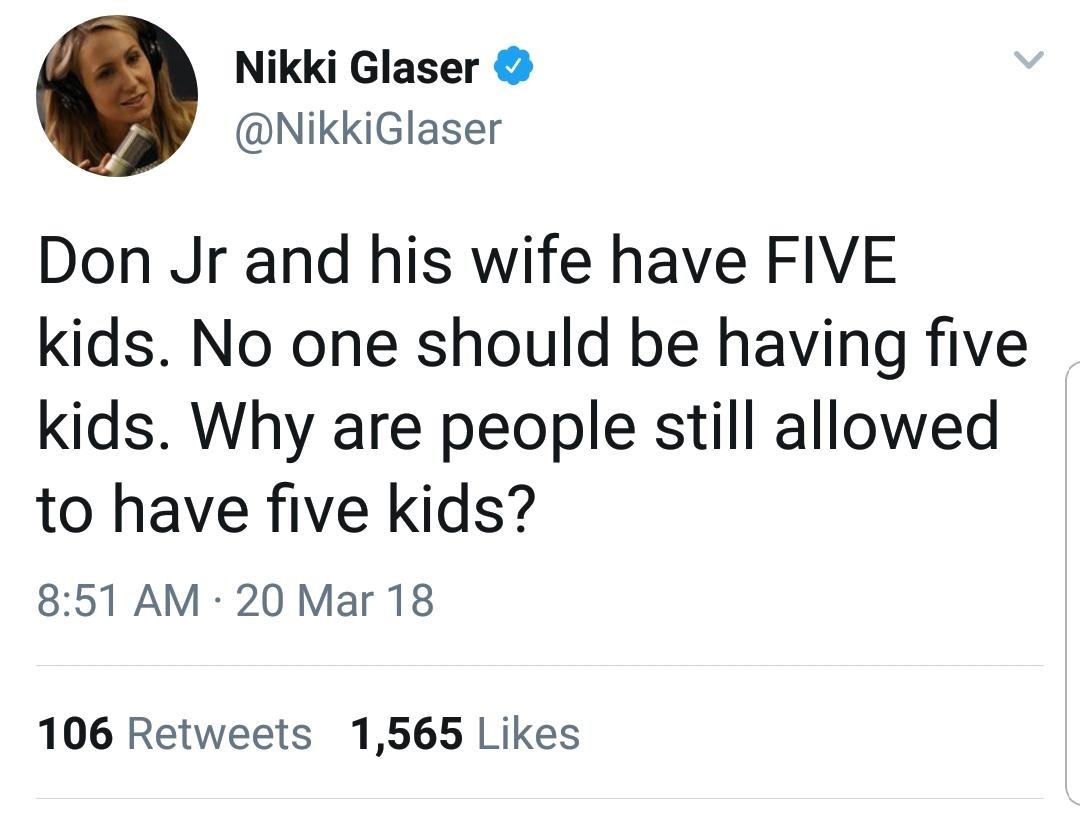

It’s not unusual for parents of big families to face criticism for having more kids than the average for their community. Reactions can range from raised eyebrows to sneering Twitter commentary. Recently, comedian Nikki Glaser tweeted about Donald Trump Jr., “Don Jr and his wife have FIVE kids. No one should be having five kids. Why are people still allowed to have five kids?”

She’s since deleted the tweet, but it’s not an uncommon complaint. Earlier this year, Chip and Joanna Gaines faced a social media backlash after announcing their fifth baby was on the way.

Most of this criticism comes from the Left, but even some on the Right criticized support for the Gaines’s family size. After all, haven’t we all heard parents of as few as three or four sigh and wish they could spend more time with each of their kids? Haven’t we heard how finances can be stretched to the limit to cover big families? Since conservatives are all about personal responsibility, shouldn’t we think twice before praising something that might be irresponsible?

As a middle child with four siblings, if anyone has grounds for criticizing families of that size, it’s me. But as I’ve written before, “I’d rather have a few months where I felt a bit ignored and have siblings for a lifetime than all the individual attention I could get as an only child, or with only one sibling.”

The Resources Per Child Argument Misses Something

Most people emphasize the time and money (which translates to quality schools, good neighborhoods, extracurricular activities, etc.) parents spend on each kid as the supreme indicator of their child’s wellbeing. While people on the Right and Left differ on how important time with parents and resources are in relation to each other, the debate is almost exclusively centered on that comparison. Feminist critics say working parents can afford more opportunities for their kids, while more traditionally minded critics argue time at home with kids can be more valuable than those things.

The measure of successful parenthood, and therefore happy, healthy childhoods, is nearly always reduced to this: how much of your life energy are you devoting to your child?

Not only is this frame of determining a child’s welfare too narrow, it is distorting our view of what makes a happy, healthy family. A family is not a series of unilateral connections that funnel resources and guidance between a parent and each of his or her children, but rather a tightly woven web of relationships among all members of the family.

On a certain level of analysis, we take a dry, economic view of childrearing and end up reducing it to an intergenerational transaction. To determine success in parenting, we ask questions like: How many hours do you spend at home with your children? How many meals do you eat with them? Do you send them to a good school? Are you getting them music lessons? Are they playing sports?

To be sure, these are important data points to measure. They can give us a bit of insight into what helps produce positive life outcomes for kids and what doesn’t. The danger lies in viewing parents as the near-exclusive source of a child’s enrichment, whether through buying them materials and experiences or through being more directly involved in their childhood.

Through this lens, we end up seeing siblings as competing for scarce “parental resources” rather than adding tremendous value to each other’s lives, and even offering significant aid to parents so they can parent more efficiently. If we view child-rearing as a zero-sum game instead of a growing basket of resources, is it any wonder that bitter criticism of big families is so prevalent in our culture?

The Opportunities Siblings Give Each Other Are Vast

The truth is that siblings are a vastly underrated blessing. They teach older siblings to look after and protect those younger and more vulnerable. They provide role models for younger siblings to emulate. That extends beyond learning to walk and talk sooner to learning responsibility and how to interact with others in constructive ways.

Siblingship doesn’t just foster cooperation, compromise, and forgiveness, it requires them. You can’t divorce your sister or kick her out of the house. Learning to get along is a necessity, and the skills and character necessary to do that will help children thrive now and much later in life.

There will be wrongs that were never righted, from the petty to the severe, that you might not ever forget. I remember being irate when my sister drew squiggly blue circles on a dolphin picture I had drawn. They were supposed to be bubbles. But I also remember she spent considerable time helping me with a college project. And when either of us are having an existential crisis, the other is just a phone call away.

Whatever their irreconcilable differences as adolescents, you’re not just giving your child a live-in playmate, you’re giving her a bond that will last a lifetime (unless you really screw it up). While five or ten years between an elder and a younger sibling might mean they won’t be very close as children, not only is it still valuable in childhood, but that maturity gap that appears an unbridgeable canyon at the beginning of life may close to a mere crack in the pavement in adulthood.

My older sister and I are five years apart, but we’re essentially at the same point in our lives: raising young children. (Don’t forget that more siblings means more adorable nieces and nephews for them to love on, too.) I’ve found the older we get, the more we have in common, and the pettier our adolescent disagreements seemed to be. Blink, and suddenly all five of us are hurling headlong through the same few passages of adulthood. College, dating, marriage, kids—for each of us, one is the present, one seems like yesterday, and another is tomorrow.

We’ve each gone about our lives a little differently, and that means we can learn from each other. We all have, or will have, similar problems. You could say that’s true with any two non-related people of the same generation, but it’s especially true for siblings. No one understands your upbringing the way they do, and no one besides your spouse, or perhaps your parents, can empathize the way they can.

Nobody Else Shares So Many Memories

Your brothers and sisters share more childhood memories with you than anyone else in your life, and those memories anchor your relationship. Lord willing, your siblings will be there even after your parents pass away, and they’re the only ones who would have known your parents the way you did. No one will share your grief like they will.

Even step siblings, half siblings, and adopted siblings are likely to share all of this with you. You may not have shared as many formative experiences, or you may have a different mother or father (or both), but that doesn’t mean your relationship is any more shallow or fragile.

Of course, there are myriad ways you can alienate even the closest brother or sister. We’re all capable of it. Like spousal relationships, they require care and a lot of forgiveness. But even if you let your bond wither and dry up for years, its roots run deep and don’t die easily. It can still be revived.

In a time when relationships run status-deep and people move from city to city or state to state every few years, such a bond is priceless. I have no doubt that if we lost all our money and were a few dollars away from the street, any one of my siblings would take me and my family in.

Multiply the Love Exponentially

No relationship is without risk. Certainly, siblingship can deteriorate to the point where living separate lives is all you can do. As a mother or father, seeing your children wound each other emotionally (or physically) will break your heart and keep you up at night. There will be sobbing and screaming, bloody jaws, and slamming doors.

But if you raise them with love and strong values, the probability that siblingship produces good fruit in your children’s lives, fruit that nourishes and strengthens them, is far greater than the chance of it poisoning your family.

In our scarcity-based theories of parenthood, the fruitfulness of siblingship is not often considered. The question we should be asking is not, “How much parental energy will my fourth child divert from my first three?” but, “What blessings and challenges will another child bring to our family as a whole?”

Giving your kid more siblings is probably the best thing you can give them beyond your love, guidance, and discipline. I’m not saying the family dynamic can’t change for the worse at a certain number. I think it’s fair to criticize situations in which older children are essentially forced into parenting their younger siblings full time because there’s simply too many kids for two parents to adequately address. But five is not that number, and six and seven probably aren’t, either.

Big families aren’t inefficient economic units. They’re interesting and loud and dramatic and fun, and they produce more lifelong relationships that will continue to enrich your sons’ and daughters’ lives long after you die. Instead of ridiculing big families or dismissing them as unworkable, critics might consider having one themselves.