President Trump recently deployed the National Guard to the southwestern border, due to concerns of chaos and lawlessness there, particularly due to the impending arrival of a “caravan” of migrants who intended to enter the United States illegally. This cohort of Central American migrants has mostly disbanded now, but concerns about the security of the border persist.

The Trump administration continues to assert that the situation on the border is an acute problem requiring major measures to enhance border security, while progressives have tended to claim that illegal immigration is near the lowest levels in years. In the midst of the argument, it can be hard to sort out which side is more supported by the facts.

The first key fact to understand is that migration patterns can change extremely quickly. A country like Venezuela can go from having a few tens of thousands of diasporans to millions in just two or three years. In the midst of major migration flows, the facts on the ground shift extremely rapidly, so keeping abreast of them is very difficult, but very important.

The situation on the southwest border is no different. The facts on the ground are changing with astonishing speed.

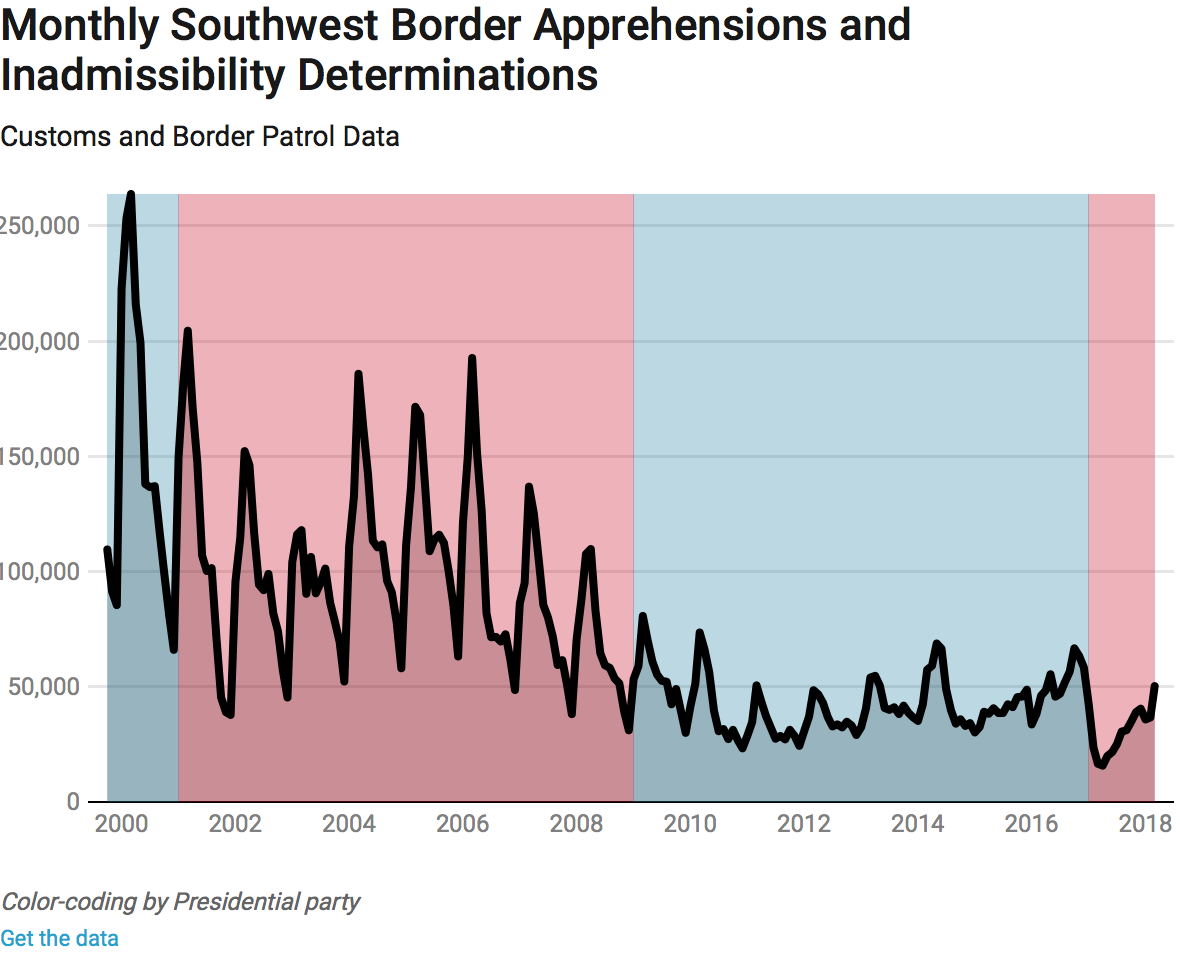

The graph above shows people deemed “inadmissible,” which means people rejected at ports of entry, like airports or border checkpoints, as well as people “apprehended.” So, that’s immigrants trying to cross a border outside of a normal crossing point, and getting caught.

Illegal immigration declined significantly during the George W. Bush and early Barack Obama administrations, then stabilized at levels much lower than observed in the 1990s, though the latter Obama years seem to show some increase. But then in early 2017, there’s a huge dip: immigrants apparently just stopped coming. Within this dataset, deemed inadmissibility falls faster than apprehensions: inadmissibility peaks in October 2016, while apprehensions peaked in November 2016.

So what happened around that time? Simple! President Trump was elected! Inadmissibles could respond faster because they basically involve conventional movement routes like airports and land crossings, while apprehensions rose for another month because those migrants were already in land transit, so it took a month or two for the Trump shock to effect flows.

Border apprehensions, a decent proxy for border flows, plummeted. April 2017 saw the smallest number of apprehensions and inadmissibles on record, at less than 16,000. While there may be other factors at work, the likely cause of this shock was President Trump’s election: his rhetorical stance against immigration probably reduced illegal inflows almost immediately.

This suggests the attitudes, words, and views a president expresses have real-world effects separate from the policies he or she adopts. It matters whether a president rhetorically coddles foreign foes like Russia or ISIS, refuses to condemn crimes like illegal immigration, and fills his language with falsehood and profanity.

But this effect has gradually worn off. As of March 2018, apprehensions and inadmissibles have risen to nearly 50,000 again, similar to the springtime-peaks observed during the Obama years. Whatever short-term effect Trump’s rhetoric may have had, with no actual new border security measures in place, it’s wearing off. Realizing that rhetoric has real, not quickly-fading, effects is probably motivating Trump’s decision to deploy the National Guard.

So when progressives say that we are at historically low levels of illegal immigration, the truth is that we were at historically low levels of immigration, thanks to a short-term Trump-led bust. But that effect is fading, and illegal immigration is rising again to the levels of the Obama administration. Of course, the total illegal immigrant population probably fell during the Obama administration as mortality, deportations, and emigration exceeded illegal immigration, but the rate of decline was quite gradual, and the number of illegal immigrants remains large.

In fact, some of Trump’s policies may be increasing illegal immigration. Many deported immigrants attempt to return to the United States due to ongoing ties here. It’s possible that in deporting large numbers of illegal immigrants, the administration may be increasing the number of people outside the United States with strong motive to come here, regardless of legal status.

While steadily deporting illegal residents may be justified as a policy, especially when focused on illegal residents who have committed other crimes, it may have the unintended side effect of boosting gross illegal inflows, even as the aggregate number of illegal U.S. residents shrinks.

But there’s another fascinating angle to the story of the migrant “caravan.” Many did not intend to simply enter the United States without legal permission; they intended to claim asylum. Claiming asylum means a person enters a country without legal right to do so, then asserts he cannot be deported, because deporting him would likely result in his death due to racially, religiously, politically, ethnically, or sexually based violent discrimination.

Asylum is enshrined as a right in both U.S. and international law. However, asylum has become increasingly controversial in the United States and Europe as a growing share of foreign citizens attempt to claim asylum, raising questions over whether this once-modestly-sized migration program faces abuse and misuse.

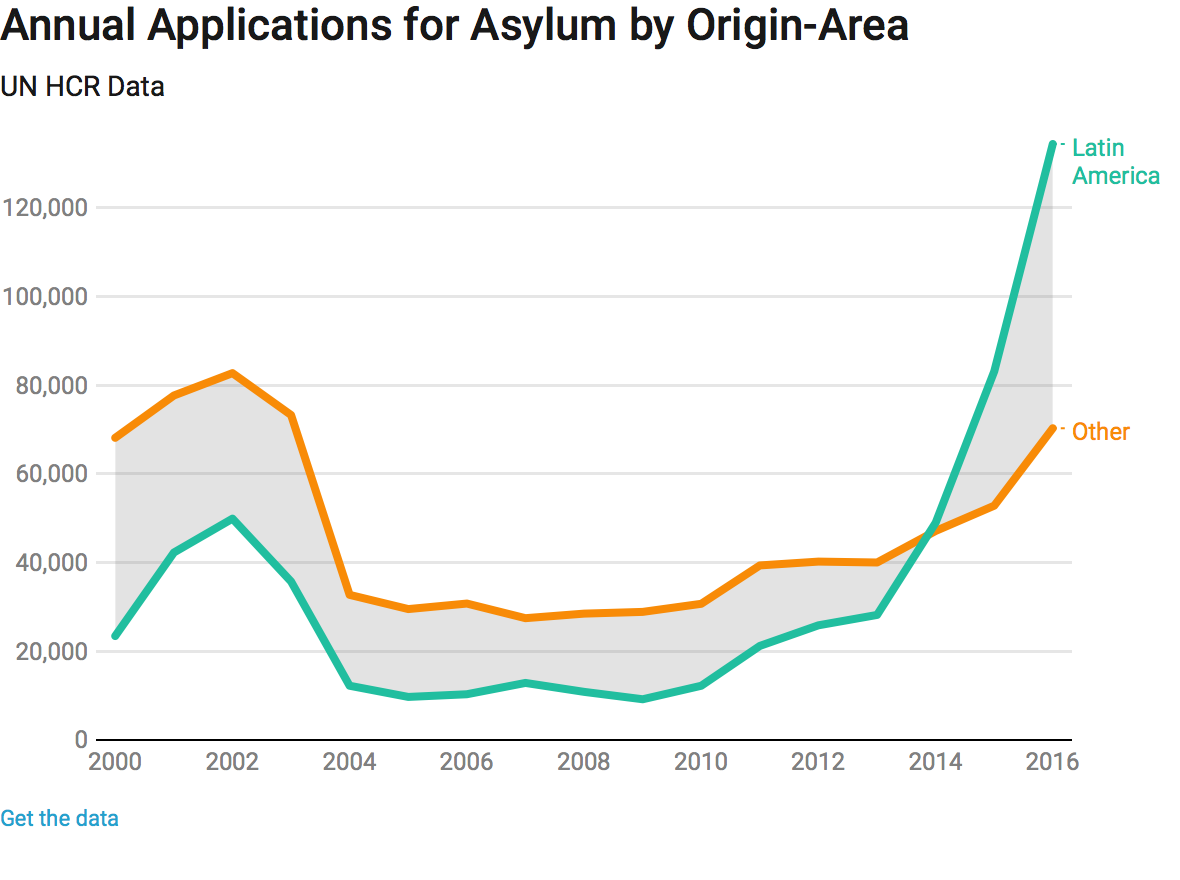

Using data reported to the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees, we can look at how applications for asylum to the United States have changed in recent years.

The graph above shows asylum applications in the United States, broken out by applicants originating from somewhere in Latin America and applicants from the rest of the world. The lion’s share of Latin American applications comes from the Central American countries.

As you can see, asylum claims have risen in recent years for all origins, but especially for Latin American origins. While once these countries were a minority of claims of asylum, in 2016, the most recent available data, they were a substantial majority.

This is a cause for concern, because, as of 2016, of all Latin American cases pending in 2000 or applied since then, just 7.4 percent have been approved, compared to 35 percent for other countries. The numbers are even worse for the Central American countries, at 4.7 percent, and Mexico, at 3 percent.

The United States rejects the vast majority of asylum claims from these countries. But in the meantime, asylum-seekers get a temporary respite. They are held in the United States as their case progresses. Some are held in Immigration and Customs Enforcement facilities, but some are released, sometimes with ankle trackers.

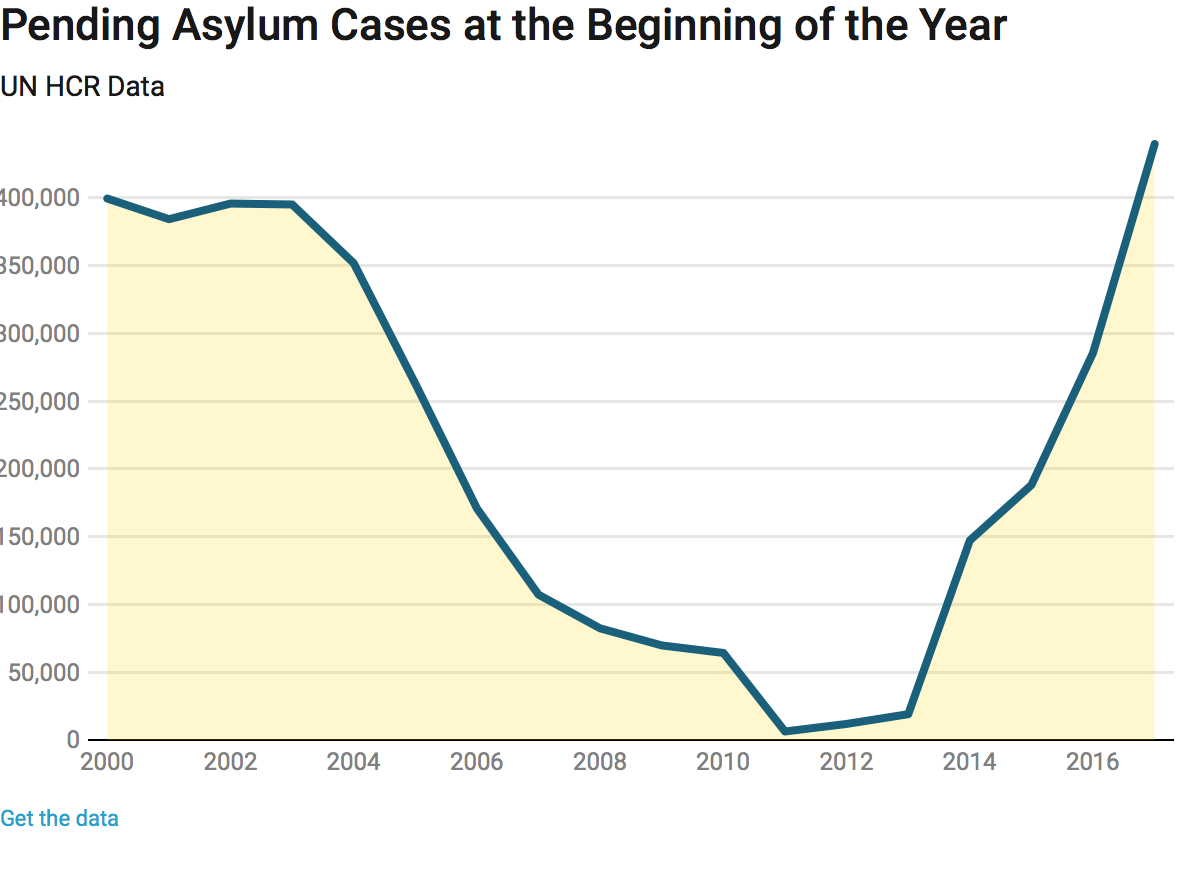

The number of actual grants of asylum by the United States has not risen in recent years from its usual 20-25,000 per year range, according to the UN. We have not become much more willing to offer asylum. The typical migrant has simply become far more likely to claim asylum. The result is a growing backlog of court cases.

The asylum system is being inundated with claimants who simply cannot all be processed in a reasonable time. A huge share of these applicants will be rejected, probably upwards of 70 percent. They will be deported, or return home voluntarily. But in the meantime, they make it harder for the court system to respond to valid claims of asylum, and in many cases cost U.S. law enforcement significant time and resources.

However, it’s far from clear how we can stop this abuse. There’s no way to simply know upfront which asylum-claimers may have valid claims. Attorney General Jeff Sessions is trying to find ways to ease the court backlog and speed up cases, but there’s a limit to how much the system can be juiced for extra efficiency. A huge increase in asylum claims is hard to deal with under any system.

I don’t have a clear solution for how to reduce invalid claims of asylum. Simply barring the border to asylum-seekers would shut out people the United States is legally committed to helping: individuals facing persecution by Venezuela’s socialist dictatorship, for example.

But the administration is not wrong to raise an eyebrow at the extraordinarily high rate of ultimately rejected asylum applications among Latin American asylum-seekers, and to want a systematic solution. These excess claims clog up a system that otherwise serves American interests by providing safe harbor to those persecuted by overbearing governments and radical extremists around the world.

Plus, these excess claims mean that even legitimate asylum-seekers from Mexico or Central America face extraordinarily long delays in verifying their legal status. If we really want to help these legitimate asylum-seekers, we should be looking for ways to prevent droves of illegitimate-claimers from filling the system with spurious claims.

Thus, overall, the administration is right to be concerned about a large group of Central American migrants traveling in a “caravan” to claim asylum en masse. That behavior can paralyze a vital component of U.S. immigration policy, and is worth trying to prevent. It’s not clear deploying the National Guard will have any effect, but some kind of response to the changing facts on the ground is probably warranted.