“Darth Vader was seduced by the other side of the Force.” Actually, it was the dark side, not the other side. Vader was seduced by a set of values in contradiction to what Jedi took for granted about the Force and its usage. Unless we dust off this most obvious of points—that conflict is the result of the conflict of values—then just what were all those space battles about? If we are not fighting over values, and moralizing about them, what is there exactly to fight and moralize over?

AEON magazine recently published “The good guy/bad guy myth: Pop culture today is obsessed with the battle between good and evil. Traditional folktales never were. What changed?” by Catherine Nichols. Nichols’ well-researched article says folk tales and ancient literature were more ambiguous in how characters and their intentions played out in the worlds of their making, whereas today there are largely two distinct teams of good guys and bad ones.

“In old folktales, no one fights for values,” Nichols writes, “Individual stories might show the virtues of honesty or hospitality, but there’s no agreement among folktales about which actions are good or bad.” That is, except maybe the virtuous actions of honesty and hospitality.

Nichols uses a variety of stories to make her point, including everything from “The Illiad” to the latest Wonder Woman movie, then points out how often moralizing seeps into the way we perceive the stories we tell, even if there is no basis for it.

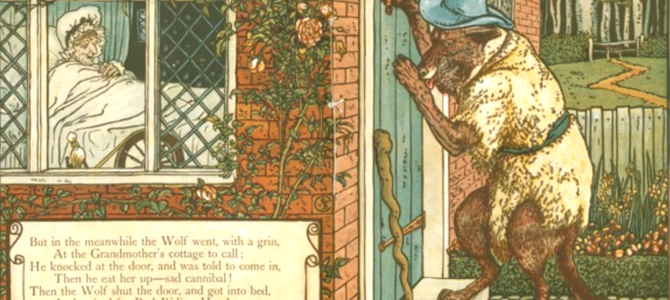

“Stories from an oral tradition never have anything like a modern good guy or bad guy in them, despite their reputation for being moralizing.” In this vein, Cinderella was beautiful merely “to make the story work.” In the tale of the Three Little Pigs, “neither pigs nor wolf deploy tactics that the other side wouldn’t stoop to. It’s just a question of who gets dinner first, not good versus evil.” Even Jack from Jack in the Beanstalk “has no ethical justification for stealing the giant’s things,” like his golden harp and golden goose.

Is Declaring a Good and Evil Propagandistic?

Beyond her historical accounts, Nichols all but claims that such modern-day moralizing is essentially the very kind of propaganda that leads to dehumanization of the other and the zealotry to commit the same kinds of crimes one often accuses one’s enemy of:

Good guy/bad guy narratives might not possess any moral sophistication, but they do promote social stability, and they’re useful for getting people to sign up for armies and fight in wars with other nations … When we read, watch and tell stories of good guys warring against bad guys, we are essentially persuading ourselves that our opponents would not be fighting us, indeed they would not be on the other team at all, if they had any loyalty or valued human life. In short, we are rehearsing the idea that moral qualities belong to categories of people rather than individuals … Watching Wonder Woman at the end of the 2017 movie give a speech about preemptively forgiving ‘humanity’ for all the inevitable offences of the Second World War, I was reminded yet again that stories of good guys and bad guys actively make a virtue of letting the home team in a conflict get away with any expedient atrocity.

Now, perhaps I am remembering these old stories very differently, but it’s also possible Nichols is conflating at least some of the themes among the stories she drafts to prove her point. That point is hard to square with the way literature is usually understood, which has a great deal to do with how we wish to understand ourselves.

There are only so many themes and variations on those themes in stories, a notion proffered by Aristotle. In fact, when researchers at the University of Vermont’s Computational Story Lab in 2016 used artificial intelligence to map more than 1,300 stories and their emotive language, they found six basic arcs: rags to riches (rise), riches to rags (fall), man in a hole (fall-rise), Icarus (rise-fall), Cinderella (rise-fall-rise), and Oedipus (fall-rise-fall). According to the results, the most popular stories were under the Icarus, Oedipus, and man-in-a-hole titles.

Stories, myths, and folktales are how humanity has passed on the values we find valuable enough to keep and repeat. If this were not true, then why are these stories remembered at all? The only self-evidence for their telling is that they are considered worthy enough to keep telling. Was Cinderella beautiful? She was. But being beautiful is not the aim of the story, or even what makes it “work.”

Fairy Tales Definitely Embed Moral Lessons

In fact, a host of morals are present in the tale—first written in 1697 by the Frenchman Charles Perrault, and repeated in many incarnations since—not the least of which is hope for your future, enduring harsh times, forgiveness of those who mistreat you, respect for yourself, and kindness toward others. In fact, at the end of his own story Perrault remarks that graciousness, not beauty, is “priceless and of even greater value.” The story also highlights that bullying is heartless—an especially important lesson for kids.

Insofar as the Three Little Pigs might have “stooped to tactics” that the wolf had employed for their dinner, they were certainly not out to eat the wolf, who was actively eating them. And only the hard-working, brick-laying ingenuity of the last pig allows him to survive the onslaught of the ever-ravenous wolf in the clearly good-versus-evil story.

As far as Jack’s ethical justification for stealing, does Nichols really believe that a kidnapped anthropomorphic golden harp should not be rescued from its misery? Or that a sickly golden goose ought not be liberated from a cold-blooded serial killer who freely admits—rhyming about it, even!—to eating young boys on toast?

Even such seemingly ambiguous tales like Nichols’ examples of early twelfth-century Arthurian legends written by Chretien de Troyes, or the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon in “The Illiad,” contain lessons regarding knightly chivalry, the application of justice, charges of injustice, and the upholding of honor, such as it was, between friends and foes in the epic Greek mythos.

Morals Are Always at the Heart of Disagreements

If we are not fighting and moralizing over our values, then just what are we fighting and moralizing over? Yes, morals do contradict. Some directly contravene others. This invariably leads to conflict in meta or physical means—plenty of folks will bash each other silly over a difference in favorite sports teams, let alone reasons that may actually be worth bashing someone silly over, like say the threatening, harming, torturing, or murdering of innocents. This conspicuousness drives the moral and ethical dilemmas of swashbuckling tales because one can only identify the “derring-dos” when there are clear prohibitions against “derring-don’ts.”

Morals constitute the roots of our motives, or how we motivate ourselves, to protect and defend what we instinctively feel, or reason to judge, to be necessary or worthy of protecting and defending. How we act (our ethics) has everything to do with how we moralize. How we moralize has everything to do with how we value. And how we value has everything to do with how we value life.

It turns out that whether we value life is not up for debate—it’s called natural law and everyone experiences it, just like they breathe air and are subject to gravity. But whether the value of life features higher or lower in our priorities amidst our often tribe-like mentalities regarding how we orient by our group’s philosophies, theologies, and politics, speaks to the very kinds of narrative lessons that have been told, are being told, and will always be told regarding good versus the bad and right verses the wrong.

Hiding the Morality Is Just Self-Deception

When we start believing, as Nichols apparently does, that we’d all be better off if we didn’t consider those pesky concerns and the moralizing lessons that they are wont to tell, we have not invented some space-age formula to illuminate the world, and are now cutting a brighter path through the shadowy oppressions of the dogmatic old. No, we will have actually given up the light and are now just stumbling around in the dark banging on a cheap flashlight and cursing its design.

From folktales to comic book movies, stories inform, challenge, and inspire us. We have always needed them to explain ourselves because the human heart contains everything between its breathtaking peaks and its deep, dank valleys. We would be remiss in our map-making if we scratched out those peaks and valleys—not only would it make for a highly inaccurate map, it would not inspire us to travel anywhere.

Do you remember that one story that had no goodness or badness about it, no rightness or wrongness, and no moral or virtue by which to recall it? It was just a simple story that started at the beginning and ended at the end. Remember that one?

No, of course not. Nobody does.