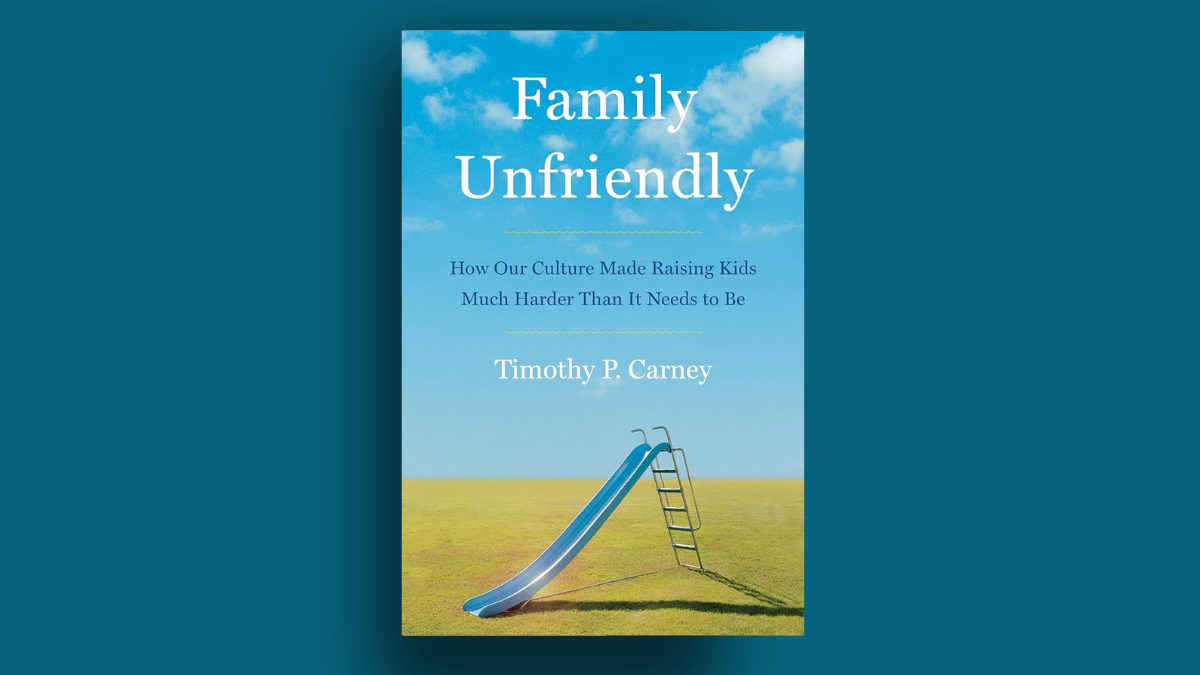

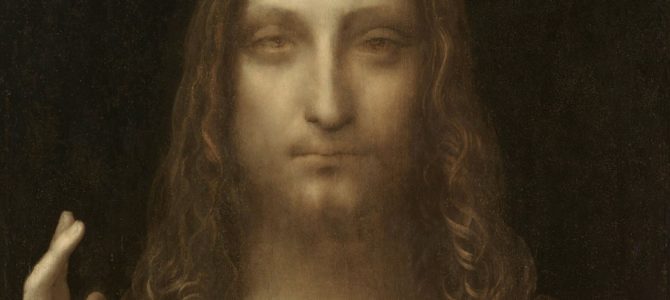

As everyone who does not live in utter isolation knows, a painting of Christ known as the “Salvator Mundi” (“Savior of the World”) by the Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci was sold recently at Christie’s in New York for more than $450 million. The painting heads to the brand-new Louvre Abu Dhabi museum after setting a record for the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction. Meanwhile, artists are seeing a spike in requests for da Vinci reproductions.

How and why it sold for such an enormous sum are fascinating questions, and we’re going to look at some possible answers. But while much of the world has been losing its mind over the money, hype, and art-speak surrounding this image, the world does not seem particularly interested in thinking about its intangible value.

How to Market a Masterpiece

It’s believed that da Vinci painted “Salvator Mundi” in about 1500, possibly for King Louis XII of France. It eventually entered various English royal and aristocratic collections before ending up in the United States, where it was purchased in 2011 by a group of investors who had it restored.

From there, it ended up in the hands of a Swiss art dealer, who sold it to a Russian oligarch. These two are currently locked in a legal battle of colossal proportions, brought in part over its selling price. The latter consigned the painting to Christie’s.

While most experts agree that it is by Leonardo da Vinci, not all have been convinced. As you can see from these images, the picture had been rather badly restored in the past. When the top layers of paint were removed a few years ago, the original, scarred image that emerged was in awful shape. Thus what we see today is an approximation of what is left of the original image, rather than an attempt to make the picture appear as it originally did half a millennia ago.

When it came time to market the “Salvator Mundi,” Christie’s took a risk. The auction house chose to include the painting, not in a sale of other Old Master paintings, but alongside works by twentieth-century artists such as Mark Rothko and Andy Warhol. In addition, they commissioned a powerful, effective marketing campaign, touting the painting as “The Last da Vinci” and sending it on a world tour, accompanied by a haunting and very effective promotional video.

After the record-breaking final sale, the level of vitriol levelled at the painting and its purchasers was something one rarely sees in art media—unless directed at conservatives, natch. The Art Newspaper for example, sneered that the da Vinci sale demonstrated “the ease with which the super rich [sic] will spend colossal sums on a trophy. Cause to rejoice, you would think, but many are shocked, even a bit sickened.”

Meanwhile, when “Untitled” (1982), a colorful but otherwise unimpressive street-art-based image of a skull by the late, highly derivative Jean-Michel Basquiat broke through the $100 million barrier last year, the Art Newspaper seemed neither shocked nor sickened that the super-rich had acquired another trophy. Then again, this is a publication that featured serious reporting on a contemporary art installation about an iguana inside a toilet biting a man on the genitals.

Even The New York Times took the highly unusual step of publishing an editorial condemning the final sale price of the “Salvator Mundi.” “Was it what Marx called ‘commodity fetish,’” they wrote, “driven to new heights in the rarefied strata of the hyperrich?” I suppose The Times keeps a copy of “Das Kapital” to hand at their Midtown Manhattan skyscraper, designed by the famous Italian luxury “starchitect” Rienzo Piano, so that they can more easily condemn the public display of wealth and luxury.

The Price of Ownership

The art market is a strange and often unhappy place, where “the three D’s”—death, debt, and divorce—are often the primary motivators behind the sale of beautiful and rare objects. It can be a difficult place to navigate, even for experts in its folkways, because a host of difficult-to-predict factors can significantly affect why something sells, and its sale price. Perhaps that’s why so many art critics and market experts were astounded by “Salvator Mundi.”

Economics professor Dr. David Hebert of Aquinas College notes that among the reasons economists sometimes have difficulty figuring out what the price of a work of art ought to be is that, these days, art is often treated as an investment rather than as an object to be enjoyed privately. “Complicating this is that, historically, the return on investment tends to be low, especially when we consider how difficult it is to resell due to the limited market. What’s even more interesting is that, in the market for masterpieces by artists such as Da Vinci, the return tends to be even lower, not higher.”

Thus, the old adage from your Econ 101 class, that the value of a good is usually determined by what the market is willing to pay for it, comes into play here—sort of. “In the final minutes of the auction,” notes Hebert, “bids for $300 million were beaten by bids for $370 million and $400 million. But this doesn’t explain why people were willing to pay such a high price in the first place.”

A key player in the information game for the art market is ArtPrice, a French company that has been collecting, tracking, and analyzing art sales figures worldwide for the past 30 years. Not only did ArtPrice correctly predict the final sale price for the da Vinci as between $450-$500 million, but it argued quite persuasively after the sale that the price makes sense, particularly given the revenues ultimately reaped by those who own and exhibit it.

One possible explanation is a shift in the world’s wealth to non-Western markets, something ArtPrice and other art market watchers have been noting for some time. “I don’t think it has anything to do with the painting itself or even the fact that it was Da Vinci who painted it,” says Hebert, but rather with the motivations of collectors in non-Western markets, who were attracted by Christie’s marketing campaign.

“These are countries that the Western World typically views as being relatively poor. Wealthy people in these countries are likely looking to demonstrate their tremendous wealth to the rest of the world in a very public way. What better way is there for Saudi Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud to do that, than by spending $450.3 million on a painting that’s smaller than a movie poster?”

In the Bleak Midwinter

Amidst all of the editorial kerfuffle and market debate, no one seems to have noticed that the cause for all of this furore is da Vinci’s attempt to portray the most important person who has ever walked this planet. In fact, the situation involving this rarity from the Italian Renaissance puts me in mind of a pictorial rarity from the Northern Renaissance, in which the artist deliberately forces us to overlook that same person.

In “The Census at Bethlehem” (1566), one of the last works of the Dutch Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569), we see one of the greatest “snowscapes” in Western art history, and a particularly rare one since snow scenes were not common in European art before then. As we look at the picture, our eyes dart this way and that, trying to take in all of the activity Bruegel records for our interest.

Among other elements, we can see what looks like a form of ice hockey being played on a frozen stream, children having a snowball fight, hunters heading out with their dogs, hordes of townsfolk crowding around an inn, chickens pecking at grains of wheat that have fallen from a bushel, and so on.

If you didn’t know the title you’d probably be forgiven for rapidly passing over the couple shown slightly to the right of center in the lower foreground. We see a lady covered by an enveloping, blue mantle, riding on a donkey and accompanied by a cow. Both animals are being led along through the snow by a man dressed in a long brown tunic. The couple are carrying their luggage, and the lady is obviously heavily pregnant, since her swollen belly just peeks out from beneath her cloak.

This is Joseph, Mary, and a soon-to-be-born Jesus, looking for somewhere to put down for the night on Christmas Eve in Bethlehem. Notice how Breughel doesn’t make the Holy Family larger or more prominent than any of the other figures in the painting, nor give them golden haloes or richly colored garments to draw your eye in their direction. In fact, we don’t even see Christ in this painting, even though he is in it, veiled beneath his mother’s flesh, and her heavy coat.

Not only do these people appear to be ordinary, but no one else in the scene interacts with them, looks at them, or pays them any attention. They’re just another part of the crowd of people making their way through the town. The savior of mankind may be about to arrive, but for these people, it’s just another manic Monday.

So is the “Salvator Mundi” worth $450 million? I don’t think that’s the real question—or at least, it’s not the ultimate one. For great art is supposed to bring us closer to understanding truth, and the subject of this particular work of art referred to himself as actually being the truth.