My wife and I homeschool our two children. For months we’ve been teaching them about early U.S. history—the Revolutionary War, the Declaration of Independence, the Boston Tea Party. They know history in the same way they know their prepositions. That means they could tell you George Washington was the first president, but what they really want to know is if there is any ice cream left.

We recently drove from Nashville to Washington DC because we wanted them to see the genesis of our country, and the American legacy they’re set to inherit. I imagined what they might say, how their sweet, young faces might express amazement at laying eyes on the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

Halfway between the White House and the Capitol, then, we stood in front of the National Archives, which contains these documents. My wife leaned close, telling me she can’t believe we have a city with buildings like ancient Greece and Rome.

It’s absolutely true: the building is magnificent. I was awestruck, thinking this must be precisely the feeling John Russell Pope had hoped to summon in people when he designed the building. Reading President Herbert Hoover’s remarks upon laying the cornerstone of the archives on February 20, 1933, I know he had the same feeling: “The romance of our history will have living habitation here in the writings of statesmen, soldiers, and all the others, both men and women, who have builded the great structure of our national life. This temple of our history will appropriately be one of the most beautiful buildings in America, an expression of the American soul.”

Then I Looked at the Kids

I looked down to see our son squinting up at the statues. I’d played out this moment in my head dozens of times over the week previous, and here we were, finally. I was brimming with prepared remarks, a father’s wisdom. I was about to make one of those memories that would stand up to the ravages of time, I knew it.

I talked about how the building is surrounded by depictions of the four watchers, the defenders of knowledge: Past, Future, Heritage, and Guardianship. We were next to the entrance on Constitution Avenue in front of the statue of the past—a female figure holding a baby and a sheaf of wheat with her right arm. On her left is an urn filled with the ashes of past generations, and at her feet is a quote from the abolitionist Wendell Phillips: “The heritage of the past is the seed that brings forth the harvest of the future.”

“Isn’t it amazing, Grover?”

“When are we gonna ride the train?”

I looked at my wife, June. “What do you think, honey?”

“We’re gonna be in this line forever.”

This pretty much sums up the day. Leaving Ford’s Theater as I monologued about Lincoln and the chaos of that night in 1864, how a few people carried the dying the president across the street to an old man’s bedroom to try to save his life, my kid chimed back: “Can we get a hot dog?”

Touching the doorframe of the Old Stone House, the oldest standing structure in all of DC: “Can we ride in a Crown Victoria taxi on the way back?” Walking along the Reflecting Pool, looking ahead to the Washington Monument: “Why are there so many bugs here? Can we go to Starbucks?”

Well, That Was a Letdown, Right?

The next morning we gathered up our things, packed into the car, and got on Route 66. I was so confused. Things were not going according to my plan. Our children didn’t have the kind of reaction I had so looked forward to.

We had one last stop, outside of DC. It was an afterthought, and we nearly didn’t go. About four hours south of DC in Rockbridge County, Virginia, at a 215-foot-high limestone arch called the Natural Bridge is where we all felt, in our own way, the full spirit of America.

Out there among the stands of ancient arborvitae trees at the southern end of the Shenandoah Valley, the stillness revealed us to one another. Standing before the arch of the Natural Bridge feels like a solemn and sacred homecoming. Close your eyes, and the waters of Cedar Creek sound like far-off applause.

Cedar Creek called to our son, the sun on its ripples, the language of its motion. He ran around the mouth of a cave where Jefferson himself mined soil during the War of 1812, when he was nearly 70 years old. That soil was purified into saltpeter used to make explosives. Our quiet daughter made whooping sounds and laughed as they echoed through the corridor.

During the Revolutionary War, the bridge was used as a shot tower. Soldiers carried molten lead up to the top and poured it into Cedar Creek. On the way down, gravity pulled drops of lead into spherical shapes. When they hit the cold water of Cedar Creek, they solidified into balls that could be fired from a rifle. My wife pointed out a Great Blue Heron, and I was so content that I felt, well, confused.

‘The Rapture of the Spectator Is Really Indescribable’

Thomas Jefferson described the Natural Bridge in his “Notes on the State of Virginia”: “It is impossible for the emotions arising from the sublime, to be felt beyond what they are here; so beautiful an arch, so elevated, so light; and springing as if it were up to heaven, the rapture of the spectator is really indescribable!”

Today the land remains virtually unchanged since 1774, when 31-year-old Jefferson purchased the bridge and 157 acres surrounding it from King George III for 20 shillings. He built a log cabin guesthouse and left a visitor’s log for travelers to sign.

That log book is long since gone, but the humanness of our history can be seen in the hundreds of initials carved into the bridge’s rock. Each was compelled to leave evidence of his presence by simply standing before something so beautiful, and strange. George Washington himself was moved to carve his initials into it as a young man of 18, when he became the first to survey the bridge in 1750. You can still see the initials “G.W.” cut into the southeast wall of the bridge.

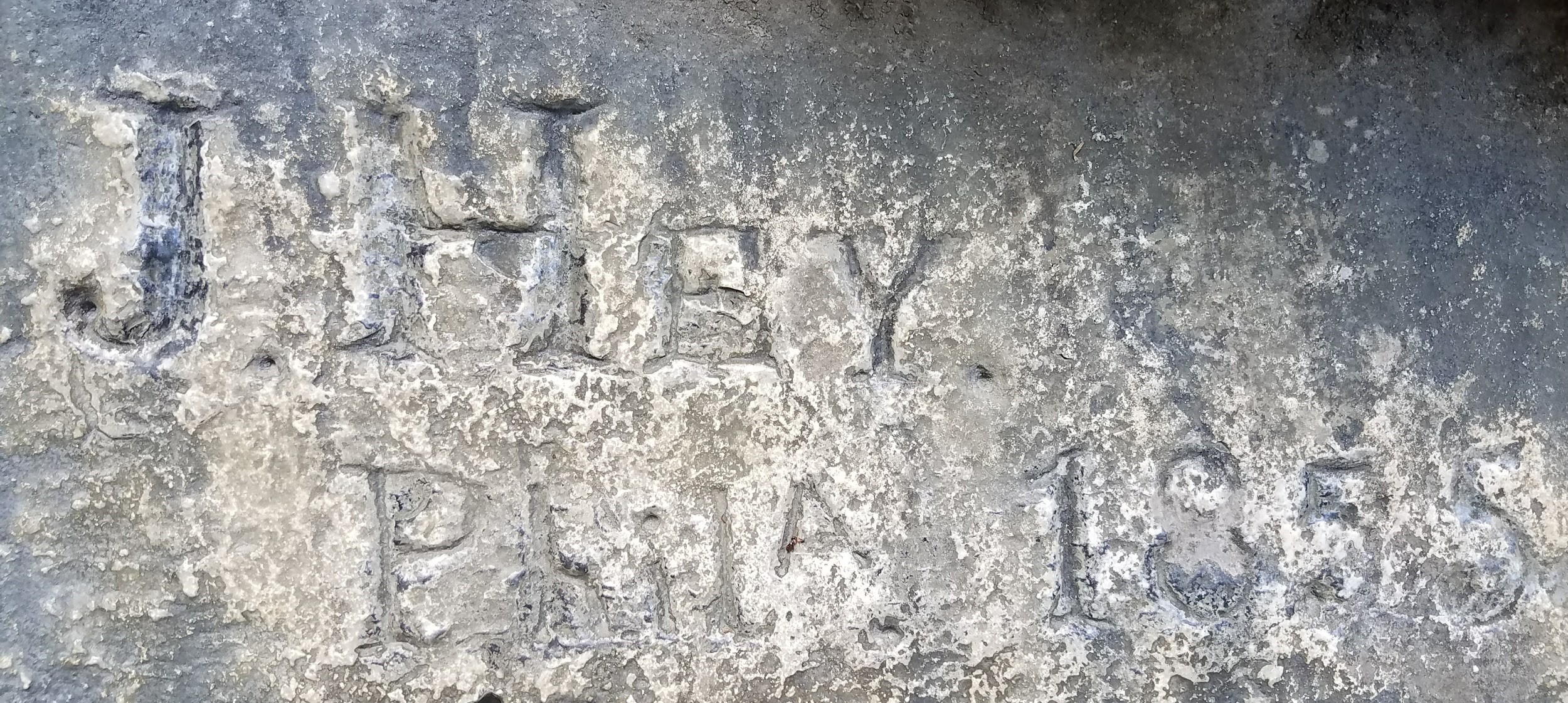

I ran my fingers across a particular engraving: J. Hey Phila. 1855.

I imagined Mr. Hey standing in that very spot some 17 decades before. He didn’t know who Abraham Lincoln was. The Civil War hadn’t yet happened. The Declaration of Independence had been read aloud from municipal steps less than 80 years prior. And here I was, with my computer chips and contact lenses, awestruck in the very same way.

Hey may well have been a son-of-a-b-tch. He might have been a gentleman. Either way, his name joins the solemn chorus of posterity, so deserving of the sweet attention of a passerby. I wanted to tell my kids about this, pack it all into some profound fatherly statement. I wanted to give them my fleeting reverence, but I couldn’t. Whatever words I have for this place, even now, are insufficient.

The sun was beginning to set behind the Virginia peaks by the time we got back to the car. I took a last look at the wellspring of the laws of nature and nature’s God, one of the wonders of the natural world, and my heart was filled with immeasurable gratitude. The determined stewardship of this land by private individuals administered over the centuries, although often curtained by the bustle of our age, is palpable here. It felt like a gift, and we were all happy to accept it.

We pulled onto Route 81 and drove toward the sunset in silence, pleased.