On Monday, the Supreme Court added four new cases to its docket, none of which captured the attention of political pundits or the populace at large. Even less noticed—yet potentially more significant—was the order issued in a case the Court did not take: Scenic America v. Department of Transportation.

Many on the Left view the newest member of the Supreme Court, Neil Gorsuch, as just another right-wing justice cast in the mold of the late Antonin Scalia. But in one significant respect, the two legal scholars parted company: their view on the deference owed to administrative agencies.

The Chevron Deference, And Why It Matters

Justice Scalia supported what the New York Times described as “an arcane legal doctrine,” Chevron deference. That doctrine, born from the Supreme Court decision in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, requires courts to defer to an agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute. Justice Gorsuch holds a much different view, as best capsulized in this passage from Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch—a case he authored before his elevation to the Supreme Court:

For whatever the agency may be doing under Chevron, the problem remains that courts are not fulfilling their duty to interpret the law and declare invalid agency actions inconsistent with those interpretations in the cases and controversies that come before them. A duty expressly assigned to them by the [Administrative Procedures Act] and one often likely compelled by the Constitution itself. That’s a problem for the judiciary. And it is a problem for the people whose liberties may now be impaired not by an independent decisionmaker seeking to declare the law’s meaning as fairly as possible — the decisionmaker promised to them by law — but by an avowedly politicized administrative agent seeking to pursue whatever policy whim may rule the day.

Gorsuch’s dicta in Gutierrez-Brizuela fueled hopes that a fresh face on the bench, and a strong advocate of judicial review, might prompt the highest court to reconsider the propriety of Chevron deference—a doctrine that feeds the monstrous administrative state. Monday’s order in Scenic America provides the first evidence that Gorsuch intends to challenge Chevron deference and that he possesses the gravitas necessary to sway his colleagues.

To explain: The plaintiff in Scenic America asked the Supreme Court to consider whether deference was owed to an administrative agency’s interpretation of a contractual term. The underlying dispute in that case involved a question over the interpretation of agreements between the Federal Highway Administration (“FHWA”) and individual states, pursuant to the Highway Beautification Act. Those agreements banned billboards with “flashing,” “intermittent,” or “moving” lights. The FHWA interpreted those terms narrowly and concluded that states could allow digital billboards without violating the contract. When Scenic America sued, the lower courts refused to interpret the contract terms and instead deferred to the FHWA’s view that digital billboards were permitted.

In seeking review before the Supreme Court, Scenic America argued that the lower courts erred in deferring to the FHWA’s interpretation of the contract terms; Scenic America claimed that courts should interpret agreements as a matter of law and not acquiesce to the administrative agency’s view. The Supreme Court denied Scenic America’s petition for review, which by itself is uneventful—it denies over 6,000 petitions for review a year and grants only about 100.

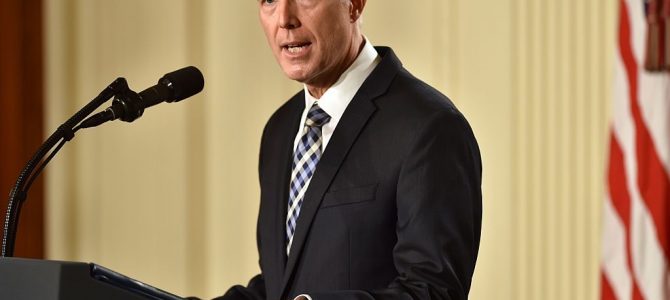

Justice Gorsuch Could Fight the Administrative State

But in this case, in denying review, Justice Neil Gorsuch issued a statement which Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito joined. Justices do not typically write separately when the Supreme Court refuses to hear an appeal, and when they do, it is usually because they believe the Supreme Court wrongly denied the petition for review. Yet in this case, Justice Gorsuch agreed that granting an appeal in Scenic America would be improvident, but he nonetheless wrote separately to criticize the deference awarded the FHWA. In doing so, Gorsuch also took a few swipes at Chevron deference, telegraphing his continued dissatisfaction with this judicially created doctrine.

Further, Justice Gorsuch’s criticism of deferring to an administrative agency when it interprets a contract it wrote, applies equally to another type of deference interchangeably called Auer or Seminole Rock deference. Under the Auer/Seminole Rock doctrine, courts defer to an agency’s interpretation of its own ambiguous regulations. But like the contracts at issue in Scenic America, an agency will have drafted the ambiguous regulations. Why should an agency’s interpretation of its own regulation merit any more deference than what is due the agency when it interprets its own contract? I can already imagine the exchanges at a future oral argument.

Beyond nerdy legal eagles, though, should anyone care? Absolutely. Because while you may not care about flashing or “non-flashing” digital billboards, with more than 430 federal agencies and other regulatory agencies there will be something you care about. Maybe it’s the HHS’s interpretation of ACA regulations. Or the Department of Education’s interpretation of Title IX—whether it be transgender bathrooms or due process. Deference dictates outcome. That is why with every passing day, President Trump succeeds in supplanting more and more of President Obama’s legacy. As for the late Justice Scalia, Chevron notwithstanding, his legacy is unparalleled and always will be.