Washington is more divided than ever, because America is more divided than ever. Seeking to insulate Washington’s elected from these divisions is not the answer. Instead, it would be better to more fully connect them to the policies that foment America’s increasingly bitter divisions.

Exit polling from last November’s election demonstrates the nation’s fundamental divisions. Among many questions, one particularly stands out: Respondents’ opinion of government. When asked if government should do more, 45 percent agreed. When asked if government was doing too much, 50 percent agreed.

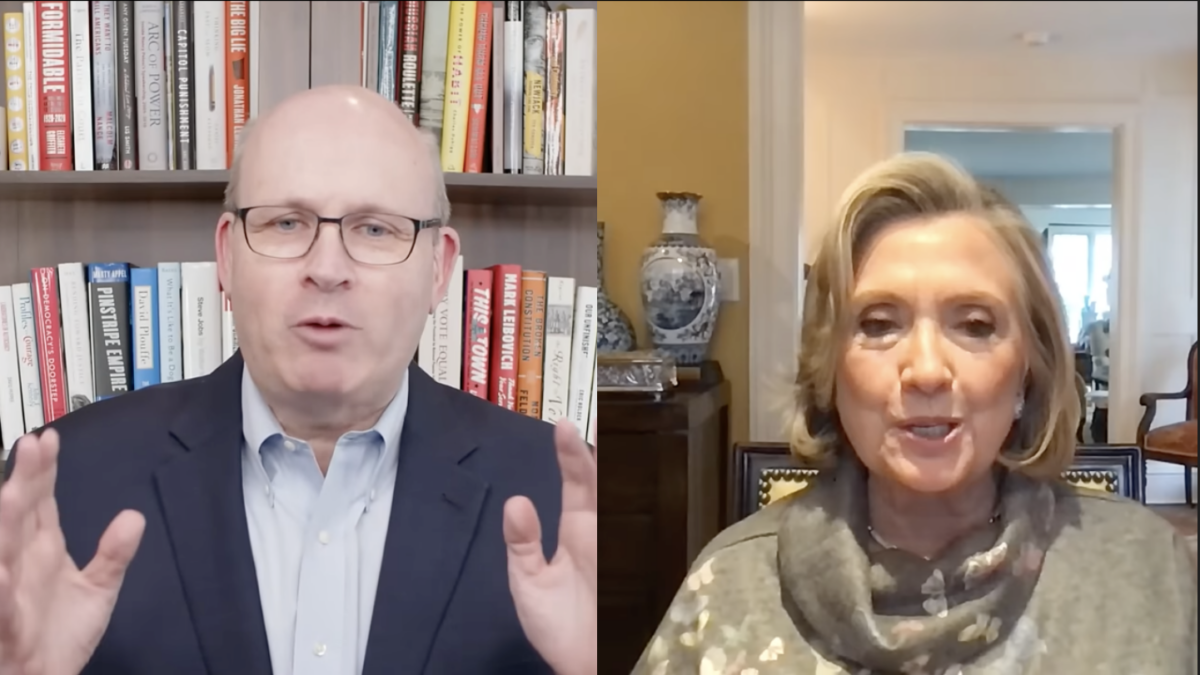

Regarding government’s basic operation, America is almost perfectly split. Respondents’ predilection for government exhibited similar symmetry. Those who thought government should do more voted 74 percent for Clinton, and just 22 percent for Trump. Those who thought the government should do less voted 72 percent for Trump, and just 22 percent for Clinton.

Not only deep and balanced, the divide has grown, at the expense of America’s middle. Combined, the ends of America’s political spectrum went from 49 percent in 2000 to 61 percent in 2016. In 2000 exit polling, 20 percent of respondents identified themselves as liberal, 29 percent as conservatives, and the rest as moderates. Last November, both liberals and conservatives had each grown 6 percent, both at moderates’ expense.

With America so divided, it is hardly surprising that Washington, where the nation’s elected and toughest issues meet, would be too. To paraphrase Shakespeare, America’s fault lines are not in our leaders, but in ourselves.

There’s Not Really a Compromise Option

Once our representatives arrive in Washington, it is hardly clear to them how to resolve these differences. There is not, and never will be, a single objective answer to America’s most pressing problems. Take the poll questions on government’s fundamental role. What is the objective answer, or compromise, between the half saying it should do more and the half saying it should do less—a little more or a little less? Maintaining the status quo? These options still mean rejecting the opinion of half the nation.

America’s political system was never intended to find illusory objective answers, but to bring subjective opinions to bear on pressing issues. While loud laments often rise over Washington’s increasing rancor and calls for the nation’s elected to bridge America’s divide, that view of the job was hardly the original one.

The Constitution frequently mentions “representatives,” “senators,” and “president.” Nowhere does it use the words “leaders” or “leader.” The intended job of the Constitution’s elected officials is first and foremost to represent—to bring the views and interests of their constituents to Washington. We frequently pillory politicians for not serving “national interests” over local ones. Yet a national interest only resides in the eye of the respective beholder, and our government was not designed around it.

It would have been simple enough to elect members of members of Congress nationally. Many nations do. Instead, they are elected in 535 separate local elections. The Senate is separated even further, with only a third elected every two years. Only the president is elected nationally. Yet it is only indirectly a national election. In reality, the presidential election is 50 simultaneous state elections. The results are decided and apportioned by state, too, further muting any national effect.

Yes, today’s division is compounded by political art—congressional districts designed to produce partisan outcomes and races run to inflame partisan passions. However, neither is new. Drawing districts to favor a particular party has existed from the beginning. We call it “gerrymandering” for Elbridge Gerry—a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Partisan rhetoric is no more original.

Our Representatives Still Deserve Blame, and Here’s Why

This does not mean the nation’s elected representatives are blameless. However, blame is not due to their lack of insulation from the divided electorate. Their blame arises from their insulation from Washington’s policies.

For decades, Washington’s elected have steadily removed themselves from the operations of programs they are supposed to administer, but have put on autopilot. Spending increases dramatically and wholly outside the legislative process. The rules that truly matter are written by unelected regulators. In legislation’s absence, courts increasingly legislate from the bench.

To understand this process’ effects, just look at the federal budget. In 1940, after eight years of the New Deal, federal receipts were 6.7 percent of gross domestic product; outlays were 9.6 percent; the deficit, 3.1 percent, and debt held by the public, 43.6 percent. In 2016, receipts were 17.8 percent of GDP; outlays, 20.9 percent; the deficit, 3.2 percent; and debt, 77 percent. According to Congressional Budget Office projections, in 2046 federal receipts will be 19.4 percent of GDP; outlays, 28.3 percent; the deficit, 8.8 percent; and over 2037-2046, the debt will average 141 percent.

Washington’s elected representatives have created a layer of political insulation. It absolves them from the consequences of an increasingly unelected and self-administered Washington. Government program faults are laid at bureaucrats’ feet, while the elected keep peace with those who elected them.

The result is political insulation from policy friction. Even as government grows larger, more expansive, and more expensive, Washington’s elected representatives are more removed from the consequences. Simultaneously, those electing them move closer to the consequences: Those paying bridle at greater costs, while those receiving seek greater benefits. While Washington’s economics offer increasingly less flexibility, its politics offer more.

Rather than seek to “elevate” the elected from the areas they represent and onto a “higher national plane,” the better course would be to truly return the elected to the voters. Have them directly run the programs and face the voters, as originally intended, and answer for politics and policies alike.