If you want to make a progressive squirm, tell him that history is cyclical. Whether they realize it or not, progressives borrow their entire worldview from Christianity, and therefore have a fundamentally millenarian view of history. The idea of cycles makes them uncomfortable.

That’s why Tom Ashbrook was so unnerved yesterday. Don’t get me wrong, Ashbrook’s radio program out of Boston, “On Point,” is usually a measured, thoughtful discussion of politics and current events. It’s one of the few NPR shows that doesn’t suffer from obvious, sometimes cringe-inducing bias.

But Tuesday’s show was a notable exception. One of Ashbrook’s guests was Neil Howe, author of a book published in 1997 called “The Fourth Turning,” which argues human history is cyclical, not linear, and that its major cycles are marked by catastrophes like war or economic collapse. Specifically, Howe and his co-author William Strauss argue that history in America and most modern societies unfolds in a recurring cycle of four stages, or “turnings,” of about 20 years each. Each stage has its own characteristics, moving in progression from maturation, growth, decay, and then destruction or crisis.

Howe has described this last period, the fourth turning, as a time when “institutional life is reconstructed from the ground up, always in response to a perceived threat to the nation’s very survival.” He identifies 1945, 1865, and 1794—World War II, the Civil War, and the end of the revolutionary era—as “fourth turnings” that constituted new “founding moments” in American history. He also says that we’re in a fourth turning right now.

It’s an interesting theory, and there’s ample historical evidence to recommend it. There’s nothing unorthodox about suggesting that history moves in cycles, of course, and the authors’ observation that our current moment in history, both economically and geopolitically, closely mirrors the 1930s is in many ways correct.

Progressives Have A Dangerous View Of History

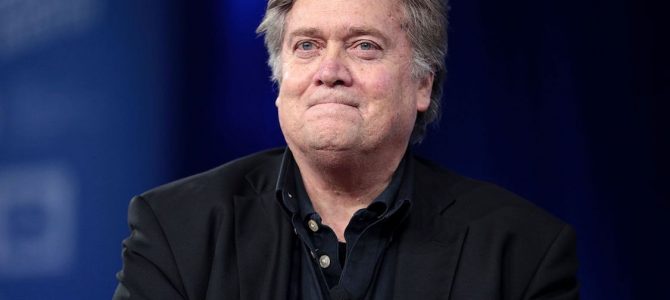

But among liberal commentators the book has now become synonymous with white nationalism and the alt-right. Why? For one reason, because Steve Bannon really likes it. But that’s not the only reason Howe’s book is problematic. The larger problem is that it refutes the progressive view of history.

As a good progressive, Ashbrook couldn’t let that lie. Setting aside his usual fair-mindedness and calm demeanor, he tried to brand Howe as an apocalyptic ideologue yearning for Armageddon. What bothers Ashbrook and other hand-wringing critics of Howe’s book is the idea that once you recognize we’re in a crisis cycle, some people (like Bannon and Trump) will want to accelerate the crisis to feed their own apocalyptic tendencies. At one point, Ashbrook asks, unaware of the irony, “Are you encouraging people to race toward the rapture here?”

Of course, a cyclical view of history precludes the idea of a “rapture.” Howe noted his book is descriptive, not prescriptive, and that a cyclical view of history is in fact the opposite of an apocalyptic view, which is all about history coming to an end. “We can navigate these periods well or poorly,” he says. “This is not anti-choice, it is simply saying, be aware of the season you’re in.”

Ashbrook countered that World War II and the Civil War were “kind of apocalyptic” because millions of people died. “It’s not something that one would steer toward given the choice,” he says.

Probably without realizing it, Ashbrook showed that a truly progressive worldview is far more dangerous than Howe’s cyclical theory of history. If you don’t believe that nations must sometimes make hard choices—say, to stamp out slavery or Nazism—then a choice will eventually be thrust upon you under far worse circumstances. Ashbrook suggested, no doubt without meaning to, that America could have chosen some other course than to destroy Nazism. But as Howe said in reply, “We had to fight them somewhere.”

Sooner Or Later, You Have to Make a Choice

Progressives take it as a matter of faith that history has sides, that it is heading in a certain direction, and that it’s up to us to usher in a secular paradise. For progressives like Ashbrook, merely anticipating a crisis in the age of Trump makes a crisis more likely to happen, which might harm the progressive cause. Hence, writers like Howe are guilty of enabling people like Bannon.

After all, humanity is supposed to be marching toward that secular paradise. Even when bad things happen—like Trump and Bannon—it’s okay because, as Obama liked to say (quoting Dr. Martin Luther King), “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Or, as Ashbrook asked Howe, “What about working for peace, justice, international equity? The things that might hold a crisis at bay?”

But because some crises cannot be held at bay, utopia can be a dangerous destination. A hundred years ago, we were determined to stay neutral in the First World War, to work for peace and justice and international equity—even in the face of a European conflict that saw mass civilian casualties and the first use of chemical weapons, on the western front. Eventually, a choice was forced upon us and we went to war, but not before millions had already been slaughtered.

Today, after eight years of the Obama administration refusing to make hard choices abroad, international crises are mounting. Before long, we will no doubt be forced to choose, despite our desire for peace, despite wanting to hold crisis at bay. Maybe it will be in Syria, where a half-million people have already been slaughtered, some of them by chemical weapons. Who says history isn’t cyclical?