Every four years, the Republican Party willingly undergoes a kind of ritual humiliation: it tries to win the state of Pennsylvania in the presidential election. No doubt you have seen film of this unrequited courtship, but in case you haven’t, voilà.

2012 offered more of the same, as Pennsylvania yanked the football away again, confirming its reputation as a White Whale of American politics.

Not everyone believes the GOP should abandon the chase. As early as 2013, astute observers were urging the GOP to invest more instead of fewer resources in the Keystone State. Pennsylvania, wrote Amy Walter of the Cook Political Report, “represents the biggest promise . . . for Republicans in 2016.” Last July, G. Terry Madonna and Michael Young, two of the most authoritative commentators on Pennsylvania politics, published an op-ed claiming the GOP could win Pennsylvania in 2016.

While hardly a consensus, by the start of this cycle the idea that the GOP could win Pennsylvania had become more than a passing fancy. The GOP really does have a good shot to win Pennsylvania. Or at least it did, until voters nominated a candidate who may keep Pennsylvania spurning Republican presidential nominees for another two decades.

Donald Trump’s Rusty Belt

Almost written off as a lost cause, Pennsylvania may in fact be indispensable to Republicans in 2016. Election analyst David Wasserman presents a compelling case that if the GOP wins in 2016, Pennsylvania is likely to be the state that clinches victory for it. The reason for this is that whereas once solidly red states like Colorado and Virginia have become more Democratic, Pennsylvania has become more Republican.

Since 1992, Wasserman calculates, Pennsylvania’s vote has shifted 0.4 percent towards the GOP per cycle. If the trend holds from 2012 to 2016, then Pennsylvania would become the third most-winnable state for Republicans after Florida and Ohio. As he points out, Pennsylvania is also favorable demographic terrain for the GOP. Its electorate is 83 percent white, its median age is the sixth-oldest in the country, and only 29 percent of whites age 25 or older hold bachelor’s degrees. On all these measures, Pennsylvania is more promising than Colorado and Virginia. These advantages may even be compounded with Donald Trump as the Republican nominee, given his overwhelming support from white voters who do not have college degrees.

Such voters dominate the states of the Rust Belt, of which Pennsylvania is part. Unsurprisingly, therefore, once Trump became the frontrunner a consensus quickly emerged: his path to the White House goes through the Rust Belt. Stories assessing Trump’s chances sprouted like spring flowers, many of them drawing a line through Pennsylvania.

Much of the attention focused on Trump’s appeal in Appalachia, and rightly so: Trump won overwhelmingly there. He is adored in the region, once a Democratic stronghold but now a Republican redoubt, while Hillary Clinton is not looked on as kindly. Appalachia extends through the western half of Pennsylvania. Like the rest of the region, it has migrated from blue to red, splitting the state in half in the process.

The focus on Appalachia and the Rust Belt ignores one crucial fact, however: Appalachia alone is not enough to win Pennsylvania. Statewide elections in Pennsylvania are for the most part decided in the eastern portion of the state, especially the Philadelphia area. Fortunately for Trump, his appeal extends even there.

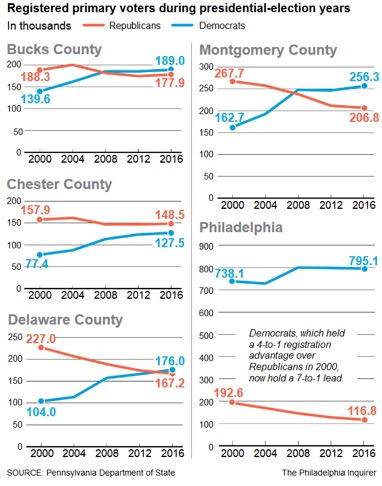

The Washington Post’s David Weigel made a considerable splash recently with a story about Trump’s popularity in the Philadelphia “collar” counties. Trump won all four counties (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery) handily. There were already signs Trump had more support in the area than the fundamentals of place and personality would have indicated. The primary revealed how deep that support was. No wonder Pennsylvania Republican leaders are hopeful “fired up” Trump voters will finally paint Pennsylvania red.

Everyone believes it: Trump can win Pennsylvania. He just has to consolidate western Pennsylvania’s migration to the GOP, capitalize on discontent with the state economy, win over disaffected Democrats, and peel off just enough suburbanites in Philadelphia. But it is easier written than done. The last step will be particularly challenging and may prove Trump’s biggest obstacle. The Philadelphia suburbs have become a graveyard for Republicans’ hopes and dreams. As yet there is little evidence Trump won’t find himself buried there, too.

Where Republican Dreams Go To Die

Trump’s problem is the same one that has confounded Republicans in Pennsylvania for years: math. Simply put, the numbers don’t add up. Since Republicans last won Pennsylvania, the state outside of Philadelphia has become solidly Republican. But Philadelphia has become even more overwhelmingly Democratic. As a result, the GOP presidential vote has collapsed in Philadelphia.

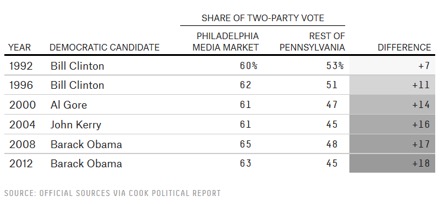

This chart compiled by Wasserman shows the divergence between Philadelphia and the rest of the state.

The Philadelphia area is much more blue than the rest of the state is red. Wasserman suggests Democrats may be over-reliant on Philadelphia and posits that the disparity “points to long-term problems for” them. But for now the problem is all on the GOP’s side of the ledger.

There are more votes in Philadelphia, and more of those votes are going to Democrats than to Republicans. In 2012, the raw two-party vote total in Pennsylvania was 5.67 million. In Philadelphia plus the collar counties, it was 1.94 million. The Philadelphia share of the vote works out to 34 percent. In other words, fully a third of all votes cast in Pennsylvania were cast in Philadelphia and its suburbs. That share has been constant since 1992.

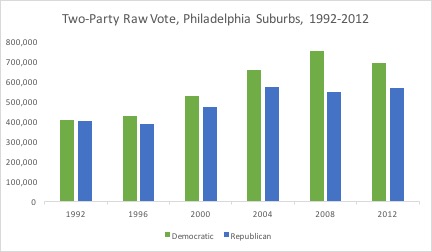

Since Bill Clinton and George H. W. Bush effectively tied in 1992 (with an assist from Ross Perot), the Democrats have gradually increased their margins in the Philadelphia suburbs, as data from Dave Leip’s U.S. Election Atlas Web site reveals.

Democrats have done a much better job than Republicans of boosting their totals in suburban Philadelphia as its population has grown. In 1992, Bill Clinton won 405,327 votes there. In 2012, Barack Obama won 689,980, an increase of 70 percent. On the other hand, Mitt Romney won 566,653 votes to George H. W. Bush’s 402,877, an increase of just over 40 percent.

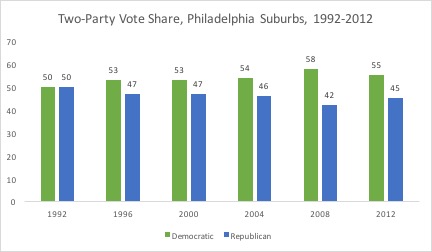

A graph of the parties’ vote share in the Philadelphia suburbs paints in even more depressing colors how badly the Democrats are eating the Republicans’ lunch.

Since 1992, Democrats have averaged 54 percent of the vote in the four suburban counties. The GOP can’t keep losing suburban Philadelphia by eight points if it wants win the state. It has to cut into these margins. Yet that goal has become harder as not only the suburban vote but suburban voters have become more Democratic. In 2000, all four counties had more registered Republicans than Democrats. Today only one does. This graphic from the Philadelphia Inquirer conveys how sharply fortunes reversed.

Philadelphia is more Democratic than ever, if one defines “ever” as “since 1992.” The GOP must climb from a deep hole. Yet many people, myself included, believe the right candidate could accomplish just that by winning the suburbs back. Alas, GOP voters went to the hardware store and bought a shovel.

That Obscure Pennsylvania of Desire

Suburbia does not like Donald Trump. It’s filled with college-educated voters, a group with which Trump performed poorly until the late primaries. Trump’s weakness with college-educated voters is the inverse of his strength with blue-collar voters, and has been recognized as such from the beginning of the campaign.

Trump’s suburban unpopularity manifested as losses in some of the most important suburban counties. Trump fared badly in the suburbs even of states he won easily, suggesting that he won despite them, a luxury he won’t enjoy in the fall. The suburbs’ aversion to Trump shows no sign of abating even now that he has all but clinched the nomination, for it is driven by a group that is normally a staunchly Republican constituency: white women. Trump has to maintain the GOP’s edge with white women just to start where Romney finished. Yet surveys and interviews suggest he has not overcome their skepticism.

This brings us back to the Philadelphia suburbs. For all the reports of Trump’s support there, substantial grounds exist to question just how popular he is or can be there. A recent Wall Street Journal story by Aaron Zitner and Dante Chinni demonstrates how daunting a task Trump faces in winning them over. Zitner and Chinni compared Berks and Montgomery Counties. Berks, which is northwest of Philadelphia, has a declining industrial base and large blue-collar population (only 23 percent college-educated). Montgomery, which borders the city to the west, is the largest and second-wealthiest of the collar counties. It is an enclave of white-collar professionals (46 percent college-educated).

Trump won Berks and Montgomery, but he won the former by 14 points more than the latter. Zitner and Chinni found Republicans in Berks much more enthusiastic about Trump than their Montgomery County counterparts, whose reactions were more muted. This makes sense: Berks is the kind of place where Trump does best, and Montgomery the kind he does worst. Trump’s problem is that Montgomery is far more important to his chances of victory than Berks.

Again, it comes down to numbers. As of late April, Berks County has 247,000 registered voters. Montgomery County has 551,000. There are nearly as many Republicans in Montgomery as there are voters in Berks. If we apply the 46 percent college-educated figure to its voting pool, we get 253,000. In other words, Montgomery County has more college-educated voters than Berks County has voters, period.

At first glance, Pennsylvania seems hospitable territory for Trump. Yet closer inspection reveals that it has some very unfriendly patches. One of the largest is the Philadelphia suburbs. Pennsylvania’s population as a whole may only be 28 percent college-educated, but that figure is higher in all four suburban counties: Bucks (37 percent), Montgomery (46 percent), Chester (49 percent), and Delaware (36 percent).

Pennsylvania Voters Are Not Just Demographically Democratic

The GOP’s ostensible demographic edge in Pennsylvania is blunted in another way. The state’s population may be 83 percent white, but it does not vote that way. In each of the last three elections (the three for which data was readily accessible), the Republican nominee has underperformed his national share of the white vote in Pennsylvania. In 2004, George W. Bush took 58 percent of the white vote to John Kerry’s 41 percent. But in Pennsylvania those figures were 54 percent and 45 percent, respectively, making the white vote in Pennsylvania eight points more Democratic.

In 2008, white Pennsylvanians were 13 points more Democratic than the nation (57 percent to 41 percent for McCain nationally versus 51 percent to 48 percent in Pennsylvania). In 2012, they were five points more Democratic (59 percent to 39 percent versus 57 percent to 42 percent). Polling indicates this trend will continue this year. Trump’s lead with white voters is 24 points in the recent ABC News/Washington Post and Fox News polls. This would be an expansion of Romney’s 20-point advantage with white voters in 2012. Yet according to the latest Quinnipiac University poll, Trump leads white Pennsylvanians by only 11 points.

The Quinnipiac poll highlights other ways Pennsylvania might remain a hollow hope for Republicans. According to the poll, Trump wins white men by 32 points, but loses white women by six. That six points is enough to help Clinton to a 43 percent to 42 percent lead. Trump loses college-educated voters by nine points. Moreover, Trump’s unfavorable ratings with white women (60 percent) and college graduates (65 percent) are so abysmal one might get the bends looking for them. Even 51 percent of white voters dislike Trump. It’s true Clinton’s numbers aren’t much better (and with white voters she’s 13 points worse), but slightly better is enough.

Winning a Huge Share of a Declining Population

To win Pennsylvania, Trump will have to maximize the white vote and bring his share in the state closer to his share nationally. Polling hints he’ll have a difficult time doing so because he runs aground on the shoals of the Philadelphia suburbs, teeming as they are with the voters he performs worst with: white women and college graduates. Trump does well with white voters, it’s true. Unfortunately for him, suburban Philadelphia is made up of the wrong kind of white voters.

Those are the voters Trump must win over if he is to have any chance at Pennsylvania. Trump can run up the score in Appalachia all he wants. It won’t matter if he’s getting crushed in the Philadelphia suburbs (and in the most recent Marist poll he was, to the tune of 61 percent to 32 percent). It’s a rich prize, but for Trump one surrounded by thorns. He needs to make inroads there, but so far he is pursuing a strategy that seems designed to alienate them as he strives instead to secure the GOP’s hold on a shrinking population.

Blue-collar whites are a diminishing portion of the electorate, college-educated whites a growing one. No Republican has ever lost college-educated whites. Trump may, because the distaff side of that cohort is not keen on him. College-educated women may be the largest segment of the white vote this year. Repelling them does not seem conducive to success. Trump might win “angry white men.” There just aren’t enough of them—not in Pennsylvania, not in the country—to carry anyone to the White House. Conquering a declining empire is not a strategy for victory, nor, in the long term, survival.

That, even more than its standard-bearer, is the problem the GOP faces in Pennsylvania: its strength is in the wrong end of the state. The shift of its western half may ultimately push it to the GOP. But this year Trump needs to stanch the party’s losses in the Philadelphia suburbs, where, for all his unwonted popularity, Clinton still beat him by 20,000 votes.

As someone who lives in those suburbs, I’m convinced the right candidate could have run strongly here. Marco Rubio, John Kasich, Rick Perry, Scott Walker, even Ted Cruz would have had a shot. Instead, the GOP’s nominee is someone who polls significantly worse than his rivals or Romney in the very states (including Pennsylvania) and with the once firmly Republican groups he must win to claim the presidency.

Such is Trump’s dilemma: to win Pennsylvania, he would need to do well in the kind of area and with the type of voter which so far have been the most resistant to him. Pennsylvania was there for the taking. Really. But voters had a different idea.

*Great White Keystone Whale beaches itself on GOP sands*

Primary voters: "Oh no you don't!"

*votes, pushing leviathan back out to sea*

— Brandon Finnigan (@B_M_Finnigan) May 1, 2016

A Republican will win Pennsylvania one day. But it won’t be Trump. And because of that, he won’t be president.

Correction: Montgomery is the second-wealthiest of the collar counties, not the wealthiest. We regret the error.