Even if you have little interest in the Civil War (and, truth be told, I fall into that category), a major exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery here in the nation’s capital is a revelation. Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) is an unusual figure, an immigrant from the town of Paisley in the Scottish Lowlands who was sometimes a proud Scotsman, sometimes a hairy mountain man, and sometimes a Victorian aesthete.

I knew next to nothing about him before seeing this assemblage of some of his major works in “Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs 1859-1872.” I came away not only the wiser, but also profoundly impressed by the man as an artist, in particular with respect to two of the many images in this comprehensive look at his career.

Many of the photographs in the exhibition will be well-known to you from books on American history. From Lincoln and Grant to Lee and Sherman, all the greats are here, sometimes on those small cartes-de-visite which must be rather like baseball cards for historians. Like this scrivener, however, you probably assumed they were taken by the more well-known Civil War photographer Matthew Brady, for whom Gardner worked before setting out on his own. Gardner, however, not Brady, was Lincoln’s favorite photographer, and one can see why in the many pictures he took of the president and his family.

Gardner’s work not only covered portraits of the famous and infamous, the battlefields and the dead, but images of an America entering a new and very different age. We see American Indians photographed in the wide-open plains, trying to hold on to their native lands against westward expansion, contrasted with the group portrait of the first Japanese diplomatic delegation to the United States. A bourgeois family poses for a stiff, formal portrait on one wall, while the poet Walt Whitman and his friends sprawl about casually, picnicking on a riverbank in another.

The Last Photograph Of Abraham Lincoln

I made a bee line for Gardner’s most famous photograph, the so-called “Cracked Plate Portrait” of Abraham Lincoln, taken on February 5, 1865. It is, appropriately, centered above and behind a round, red velvet ottoman with a central back pillar, or “conversation sofa,” like one would have seen in a Victorian parlor of the time. This image is the only original print of this image in existence, and alone worth the trip to the National Portrait Gallery, for it is rarely shown to the public.

When Gardner took the picture, the glass negative cracked, and he was only able to make one print from it before having to throw the negative away. At the time, he was not worried, for Lincoln planned to come in for another portrait sitting. The appointment never happened, because the president was assassinated two months later. It was the last formal photograph taken of Lincoln before his death.

It is a fascinating image, for as the accompanying placard points out, Gardner’s crispness and attention to detail is apparent in the cheeks and nose, but the rest of the image is fading into a soft distance. With hindsight, we can look at it as an almost prophetic image: Lincoln the man transitioning into Lincoln the myth. The self-made man from the Midwest is becoming the monumental figure seated in a temple on the National Mall.

Finding Lincoln’s Assassin

In the same room hangs what, for me, was not only the best image in the entire show, but also an example of how an exhibition can hold pleasant surprises for us to discover. Unfortunately, because photography is not permitted in the exhibition, I cannot share with you the image. I was able to locate a cut-down version of the photograph from The Met, which illustrates this blog post, but the full image is more balanced and beautifully lit. The second image, not in the NPG show, can be seen below and in that post, where the two images are compared and an animation of their movement from one photograph to the next can be seen.

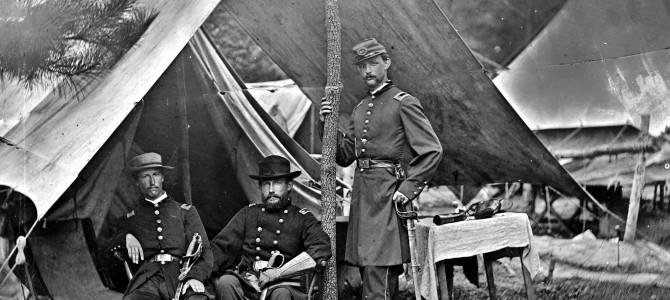

The photograph “Planning the Capture of Booth” taken in April 1865 exists in these two, slightly different versions. Both depict the three men charged with finding Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth. From left to right, they are Lieutenant Luther Byron Baker, his cousin Colonel (later brigadier general) Lafayette Curry Baker, chief of the Secret Service, and Lieutenant Everton Judson Conger.

We should take a moment here to admire the hair and the beards of these three gentlemen. Whether you are full hipster or anti-beard, these chaps not only have mighty fine heads of hair, they have spectacular beards. One could easily see them appearing on Scott Schulman’s “The Sartorialist” blog even today.

What Composition Adds to the Photographic Story

The image in the NPG show, shown below in its cropped form, is clearly the superior of the two, for it is a masterpiece of both lighting and composition. Conger is photographed in full profile rather than in three-quarters, mirroring the full profile of Baker across the table, while the angle of Baker’s head is slightly tilted to his left, and more flattering in the way his face is lit.

Although both photographs feature inverted pyramid compositions, that in the NPG exhibition is more aesthetically interesting than the other, which is more conventionally balanced. The asymmetrical symmetry of the photograph in the NPG show has greater impact when seeing the entire image, for in it, Conger’s comparatively more upright pose causes the eye to travel from left to right across the picture and then upward into the room, with its high ceilings and the unseen window behind Conger’s back that lights the group.

This is an image of classical appearance but with detail creeping in to make what might otherwise seem a tableau more realistic and more truthful. Its imperfections—the stained wallpaper, the bumps in the carpet—speak to a rejection of the stagey quality that had brought about the photograph itself in the first place. Gardner’s image places us in a world of transition from the stiffly academic to the tangibly realistic to the hazily impressionistic, a transition about to take place in the art of painting just a few years after this photograph was taken, when Monet, Degas, and Renoir (among others) held the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris.

While this is undoubtedly my favorite image in the exhibition, there are many more beautiful and haunting photographs to admire and linger over in the NPG show. You will come away from the experience not only better-informed, but also more keenly appreciative not only of Gardner’s work and of the power of this particular medium, which continues to enthrall us today. Whether you are a history buff, a photography aficionado, or just interested in good art, there is something in this excellent exhibition to attract everyone.

“Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs 1859-1872” is at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC through March 13, 2016.