Got to keep searching and searching

Oh, what will I be believing and who will connect me with love?

Wonderful, wonderful, wonder when

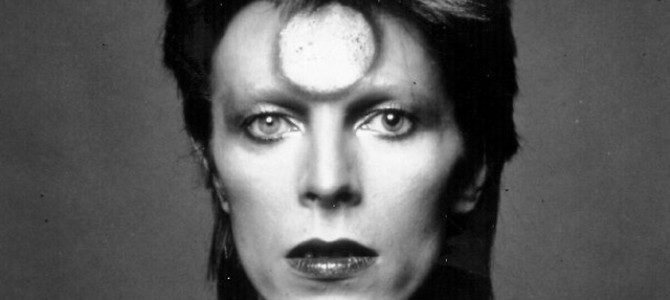

—David Bowie, “Station to Station”

On January 8 I had a wedding rehearsal and dinner that went late, which meant record stores were closed and I couldn’t buy David Bowie’s latest album on Intergalactic David Bowie Day. I felt like a failure as a fan, but contented myself with listening to KEXP DJs sharing rarities over the airwaves as I drove the hour from Maple Valley, Washington, to Seattle and back again. Some things (like your best friend’s wedding) are more important than even Bowie.

Back in DC Sunday night, I tried to sleep through my jet lag with a little pharmacological help. I woke just after 2 a.m. to an email from an old friend: “RIP Bowie. God rest his crazy, creative soul!” with a link to a British news story.

It had to be fake. A publicity stunt. Some mistaken rumor, like what happened when his last album came out and Grantland got a weird tipoff that he had died.

You can believe these things on Benadryl. You can’t believe them once the official obituaries snowball into an avalanche of pixels and words and memories, cascading down Internet clicks and television screens and public radio waves.

Bowie is dead. Long live David Bowie.

The weird thing is that I mean it. For some gut-level, intuitive reason (possibly my own willful fantasy), I have a stubborn suspicion that we’ll get to see Bowie again some day.

How Paganism Leads to Christianity

Bear with me here. I can see the eye rolls and I know you’ve read plenty of websites trying to make every celebrity out to be a secret super-Christian. But what if David Bowie—who pursued pagan pleasure until it led him to the end in his darkest cocaine-addicted days—what if David Bowie lived what Chesterton prophesied about the return to paganism?

The great psychological discovery of paganism, which turned it into Christianity, can be expressed with some accuracy in one phrase. The pagan set out, with admirable sense, to enjoy himself. By the end of his civilization he had discovered that a man cannot enjoy himself and continue to enjoy anything else.

If we do revive and pursue the pagan ideal of a simple and rational self-completion we shall end–where Paganism ended. I do not mean that we shall end in destruction. I mean that we shall end in Christianity.

Bowie’s extremely well documented drug addiction led him to a dark place by the mid-70s. An older Bowie, looking back on his career in front of a studio audience, explained it this way:

In 1975 and 1976… and a bit of 1974… and the first few weeks of 1977… were singularly the darkest days of my life. And I think it was so steeped in awfulness that recall is nigh on impossible, certainly painful. And I was concerned with questions like: ‘Do the dead interest themselves in the affairs of the living?’… Unwittingly, this next song [“Word on a Wing”] is therefore a signal of distress. I’m sure that it was a call for help.

I dare you to listen to that song today without crying just a little bit.

‘Searching for Music Is Like Searching for God’

He told 60 Minutes that “searching for music is like searching for God. They’re very similar. An effort to reclaim the unmentionable, the unseeable, the unsayable, the unspeakable, all those things, comes into being a composer and to writing music and to searching for notes and pieces of musical information that don’t exist.”

Bowie always maintained he was a dabbler, trying salvation through “Nietzsche, Buddhism, Christianity, and pottery, but singing is what stuck.” He gave an interview in 2003 where he said that he’s “not quite an atheist, and that worries me”:

I honestly believe that my initial questions haven’t changed at all. There are far fewer of them these days, but they’re really important. Questioning my spiritual life has always been germane to what I was writing. Always. It’s because I’m not quite an atheist and it worries me. There’s that little bit that holds on: Well, I’m almost an atheist. Give me a couple of months …

What do you see yourself doing in the next few years?

My priority is that I’ve stabilized my life to an extent now over these past 10 years. I’m very at ease, and I like it. I never thought I would be such a family-oriented guy; I didn’t think that was part of my makeup. But somebody said that as you get older you become the person you always should have been, and I feel that’s happening to me. I’m rather surprised at who I am, because I’m actually like my dad! [Laughs]

That’s the shock: All clichés are true. The years really do speed by. Life really is as short as they tell you it is. And there really is a God–so do I buy that one? If all the other clichés are true… Hell, don’t pose me that one.

Life really is as short as they tell you it is. And there really is a God. But don’t ask Bowie directly.

Maybe the Mockery Was an Act

I know people made a big deal about one of Bowie’s recent videos using tired tropes of lecherous priests to attack the church. But what if—and this is a big what if, I know—what if that juvenile theater was really a brilliant bit of misdirection?

We have precedent to make us wonder: Bowie’s famous bisexuality was a put-on. Bowie appropriated the gay elite scene in London for his own postmodern personae the way he did Kabuki theater and mime. It was theatrical and spectacular and shocking.

He said in the ’80s that his claim he was bisexual (“I was experimenting”) was the biggest mistake he ever made, but it served his stage persona well (and didn’t hurt him with the ladies, by his accounts). Camille Paglia explains:

Bowie virtually never did straight drag (a rare exception is the “Boys Keep Swinging” video in 1979.) Ziggy Stardust was not a drag act—he was a shamanistic daydream, half kabuki, half Weimar cabaret. With the Thin White Duke, Bowie did a rigorous, self-purging exercise in minimalism, exactly as John Lennon had done on his Plastic Ono Band album, where the Beatles’ studio excesses were stripped away and all that remained was a cool, lucid, echoing piano. As the Thin White Duke, Bowie shifted into Byron-in-exile mode; he was now a haughty, self-shielding arbiter of elegance in the Baudelaire manner.

Love that last phrase, “self-shielding arbiter of elegance.” That sense of artifice, of distance, of a put-on is what made Bowie’s performances somehow ring true. There was no “authentic” self to deal with, but in what may be called artistic humility, a work that promises not navel-gazing autobiography but pure invention.

Our Father, Who Art in Heaven

And yet. We have glimpses, don’t we? Bowie at his most transcendent gave us “Heroes,” a song of lovers triumphant in the face of death, of oppression, of the Berlin Wall. There is something real here as his falsetto insists “We can be us, just for one day.”

After 50 years of music, what we see is a man who didn’t want to be known by us, but who “needed to sing because no one else was singing my songs.” We do not know where he is now, but we may take comfort with this prayer he offered, sincerely and truly, for Freddie Mercury after his death and for other AIDS victims in 1992: “I’d like to offer something in a very simple fashion that is the most direct way that I can think of doing it.”

Millions were watching, but that unrehearsed moment (see the shock on his bandmates’ faces) may be the closest Bowie ever gave us to seeing himself.

May he be at rest with Jesus.