Ted Cruz “consolidates support” among evangelicals, according to the Washington Post; evangelicals have “found their man,” in Cruz, according to Slate; and he is “locking up the evangelical vote,” according to Politico.

Maybe—but not this evangelical. I am a theologically conservative evangelical Christian. I grew up in a loosely Baptist Bible church and gravitated to the Reformed tradition as an adult. I am pro-life and vote for pro-life candidates. I do not plan to vote for Cruz in the primary election.

Cruz has bad political theology. I mean he betrays a misunderstanding of the relationship between politics and religion. His error is the opposite of the secular, progressive left: they want no contact between the two whatsoever, and a state-sponsored secularism in the public sphere. That’s obviously a non-starter. But Cruz offers the wrong solution: Christian identity politics.

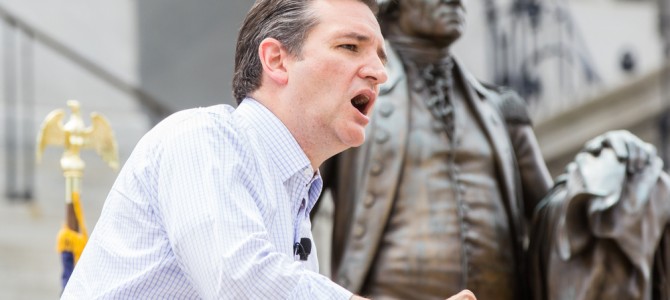

Ted Cruz’s Christian Identity Politics

When Cruz announced his candidacy, he made his parents’ and his relationship with Jesus a major emphasis of his personal narrative. Normally, I prefer candidates to talk more about religion than they usually do. But in Cruz’s case, he seemed to imply that, because of his personal narrative, we should think of him as the evangelical candidate and vote for him out of tribal loyalty.

“Today, roughly half of born again Christians aren’t voting,” he said. “They’re staying home. Imagine instead millions of people of faith all across America coming out to the polls and voting our values,” which, he clearly believes, means voting for him.

If Donald Trump has become the candidate of white identity politics, Cruz is the candidate of Christian identity politics. I dislike identity politics of all stripes and feel insulted when a candidate appeals to me on the basis of my demographic.

I have a brain. I care about ideas. I want to vote for a candidate who shares my sense of justice, not who promises to bring the most benefits to people like me. Politics should be about justice, not about dividing the spoils of state power among the interest groups who took it over.

The State Is Not a Church

As I look at American statesmen today and throughout history, I see many non-evangelicals who have done a remarkable job working for justice and the public good. For example, I am grateful for God’s common grace in providing statesmen like Thomas Jefferson (a deist), who played a crucial role in America’s founding. In 2012, I felt more comfortable with the political platform of Mitt Romney, a Mormon, than Barack Obama, who attended a Protestant church for most of his life. This year, I support and advise the campaign of Marco Rubio, a Roman Catholic.

Cruz takes this faulty political theology onto the grand stage of history. Like most Republicans, he rightly describes the United States as an exceptional country. But in his view, American exceptionalism is a function of her exceptional relationship with God. “From the dawn of this country, at every stage America has enjoyed God’s providential blessing,” he said.

America is exceptional, but not because of any special access she enjoys to God. The United States had a highly unique origin in the acts of the Continental Congress and Constitutional Convention, and its national identity is uniquely rooted in ideas of equality and liberty, rather than race, class, or language, as had been the case for most European countries at the time.

But America is not the special vehicle of God’s purposes in the world. Some conservatives love to quote Psalm 33:12, “Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord.” The nation whose God is the Lord is the Christian Church, not the United States. The church, not the United States, is the vehicle of God’s purposes in the world. To believe otherwise is to confuse the nation with the church, the spiritual with the temporal. That sort of confusion can justify all sorts of dangerous messianic political movements.

America Promotes Religious Liberty, Not Sameness

Cruz weaves his political theology into a narrative about Christian persecution and religious liberty. He held a rallies for religious liberty last August and November, the former featuring “special guests victimized by government persecution.”

I’m sympathetic to the policy argument here—that the government’s overweening progressive dictates have put some Americans in the position of either disobeying the law or violating their consciences. But Cruz’s emphasis suggests what he is really worked up about is that Christians are suffering. I’d like to hear a candidate explain that it’s wrong to violate a citizen’s conscience, no matter what religion they adhere to.

To be clear, I end up on broadly the same side as Cruz on some a lot of domestic policy issues (I don’t care for his foreign policy). I applaud his advocacy for more limited government and the rights of the unborn. What I object to is Cruz’s tone and rhetoric.

Cruz would be a divisive failure as a national leader. To be clear, my complaint is not that Cruz is mean; it is that Cruz is parochial. (David Brooks’ criticism of what he called Cruz’s “brutalism” was odd. Nice politicians finish last.) Cruz misunderstands what leadership of a religiously pluralistic people requires. Or perhaps he simply misreads American culture: Cruz is running for president of a Christian America that no longer exists—if it ever did. (This also means Cruz would also certainly lose the general election.)

Russell Moore, the head of the Southern Baptists’ Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, has repeatedly argued that Christians must find a different tone in public discourse. In past generations we could assume nearly all our fellow citizens were professing Christians and that American culture self-consciously wanted to echo Christian values. That is no longer the case. Evangelicals are a “prophetic minority” in a post-Christian society.

Let Caesar Have What Is Caesar’s

That doesn’t mean we stop advocating for what we believe—that’s our right in a democracy, no matter what the progressive movement says. But it does mean we sound shrill and look like bullies when we act like we have a right to own the culture or get elected by virtue of our religion, as Cruz often seems to do. We need to speak in ways intelligible and persuasive to non-Christians. I see little evidence that Cruz can do that.

America, as G.K. Chesterton quipped, is a nation with the soul of a church. Like a church, we are founded on beliefs and have a sense of purpose and mission to our collective existence. Like the church, America tries to welcome people from anywhere of any background so long as they sign up to our creed. That makes America a uniquely cosmopolitan power and a “dangerous nation” to the powers of the Old World.

It also introduces a temptation to American politicians. Because we have the soul of a church, politicians can easily confuse church with state. The mission of the church and the mission of the United States are different (although they can sometimes be complementary, as when the United States champions religious liberty abroad).

The two missions seem to be drifting apart as American culture becomes increasingly non-Christian. But regardless, we need to remember, as Moore says, “the end goal of the gospel is not a Christian America. The end goal of the gospel is redeemed from every tribe and tongue and nation and language in a New Jerusalem.”