In the companion essay to this, I reviewed the history of presidential elections that followed the re-election of an incumbent president, with particular attention to “battleground” states, defined as follows:

First, looking prospectively from the prior election, I included every state in which the incumbent won at least 45 percent but less than 60 percent of the two-party vote. Second, looking retrospectively to identify battleground states that didn’t look like battlegrounds four years earlier, I included states outside that range that flipped to or from the incumbent party in the Electoral College. I did not include states that flipped between the challenger party and a third party, unless they met the other criteria, although those were rare.

That essay includes a closer look at the state-by-state breakdown of the 1928 election to show why the shift in the two-party presidential vote against the incumbent party (the Republicans) had no impact in the Electoral College. In most elections, that has not been the case. What follows is the state-by-state breakdown of the other 16 elections going back to 1836.

Key:

Red: States that went Republican in both elections

Blue: States that went Democrat in both elections

Purple: States that flipped from the incumbent party to the challenger party

Tan: States that flipped from the challenger party to the incumbent party

Light green: States that flipped from the incumbent party to a third party or from a third party to the challenger party

Dark green: States that flipped from a third party to the incumbent party

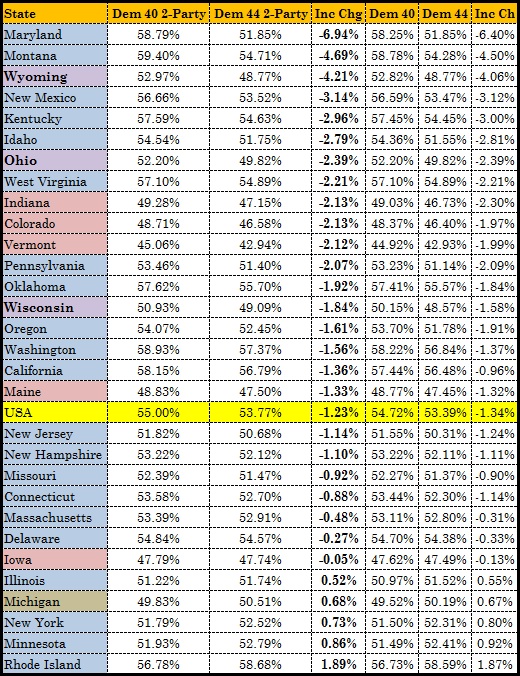

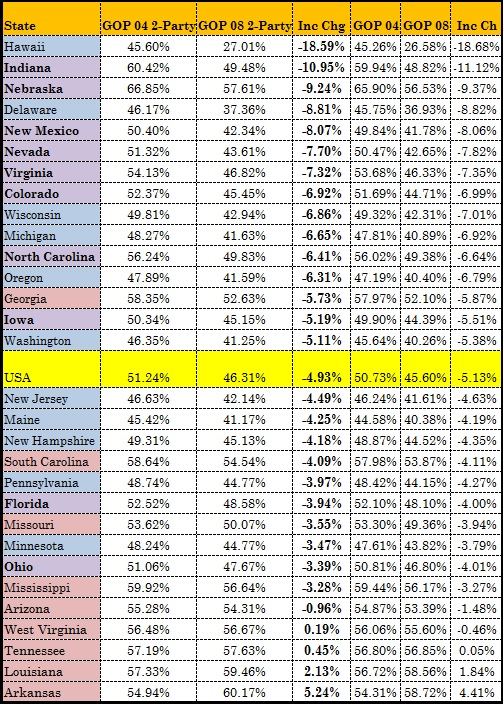

2008: The End of George W. Bush’s Coalition

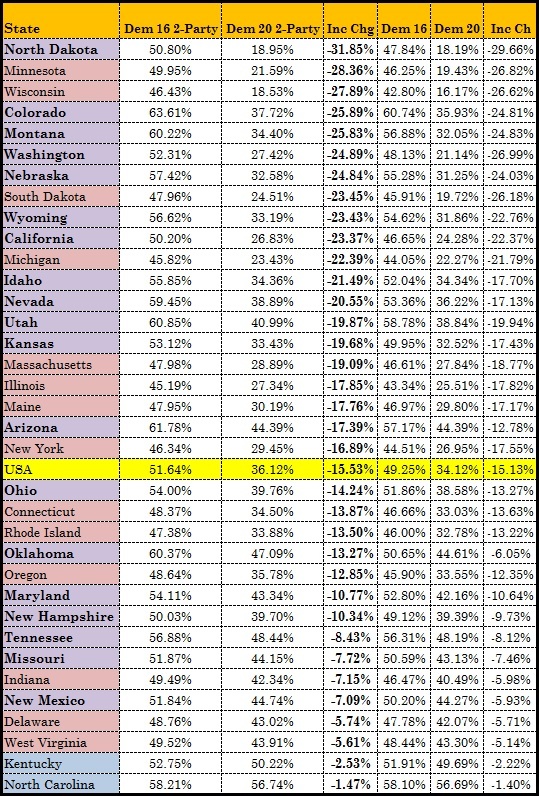

The 2008 election was unusual due to the September financial crisis, but it should nonetheless disabuse us of the notion that a 3- or 4-point movement in the two-party vote in a battleground state is a really remarkable thing to happen, as 26 battleground states—half the country—moved that far in 2008, 25 of them away from the incumbent GOP.

The 2008 election was unusual due to the September financial crisis, but it should nonetheless disabuse us of the notion that a 3- or 4-point movement in the two-party vote in a battleground state is a really remarkable thing to happen, as 26 battleground states—half the country—moved that far in 2008, 25 of them away from the incumbent GOP.

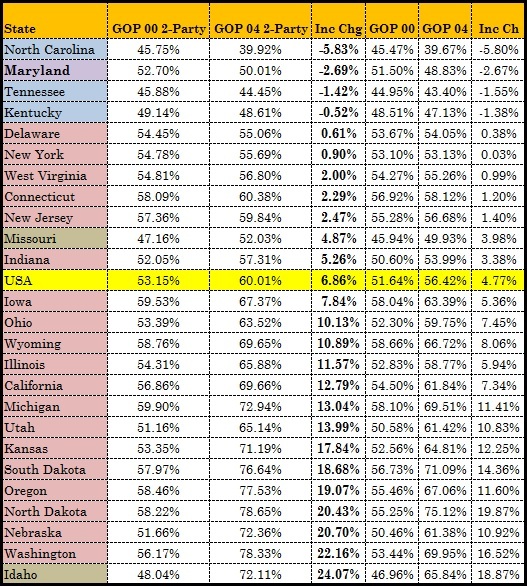

2000: George W. Bush Brings The Perot Voters Home

You will notice home states do matter—Hawaii and Delaware were both big movers towards the Obama-Biden ticket in 2008, and Arkansas heads the list of states where the Democrats did a lot less well without Bill Clinton running (watch Illinois in 2016 for signs of this, although Hillary Clinton may play up the fact that it’s her home state, too). There was no economic or world crisis in 2000; the voters were just ready for a change of pace and found a Republican candidate who could end the Ross Perot rift that split the Right in 1992 and 1996. Notice that Bush won four states where Clinton had carried between 55 and 59 percent of the two-party vote against Bob Dole.

You will notice home states do matter—Hawaii and Delaware were both big movers towards the Obama-Biden ticket in 2008, and Arkansas heads the list of states where the Democrats did a lot less well without Bill Clinton running (watch Illinois in 2016 for signs of this, although Hillary Clinton may play up the fact that it’s her home state, too). There was no economic or world crisis in 2000; the voters were just ready for a change of pace and found a Republican candidate who could end the Ross Perot rift that split the Right in 1992 and 1996. Notice that Bush won four states where Clinton had carried between 55 and 59 percent of the two-party vote against Bob Dole.

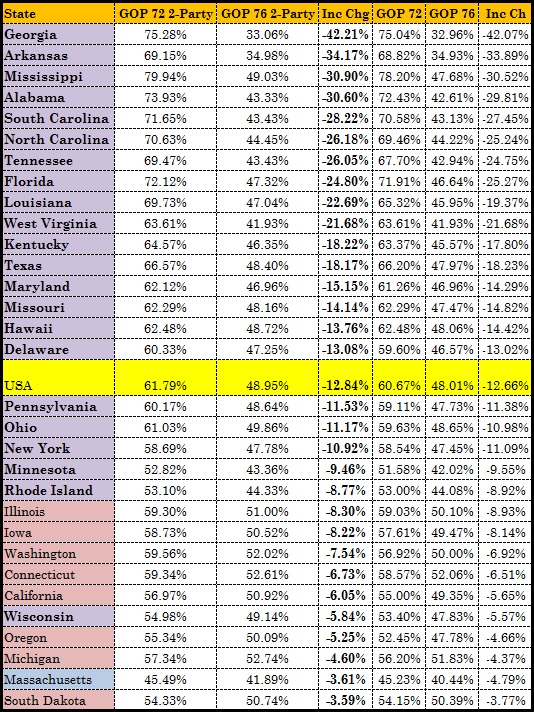

1988: George H.W. Bush Rides the Tail of the Reagan Wave

Hawaii has a pronounced tendency to support incumbents, so it again appears at the top of the list when a Republican leaves office and its natural Democratic tilt reasserts itself. The cracks were also showing in fading Republican strongholds like California, Michigan, and Vermont. Bush ran, more or less, on four more years of Reagan; that message was never going to bring new voters into the tent, but the tent was crowded enough to stand some departures for one more cycle.

Hawaii has a pronounced tendency to support incumbents, so it again appears at the top of the list when a Republican leaves office and its natural Democratic tilt reasserts itself. The cracks were also showing in fading Republican strongholds like California, Michigan, and Vermont. Bush ran, more or less, on four more years of Reagan; that message was never going to bring new voters into the tent, but the tent was crowded enough to stand some departures for one more cycle.

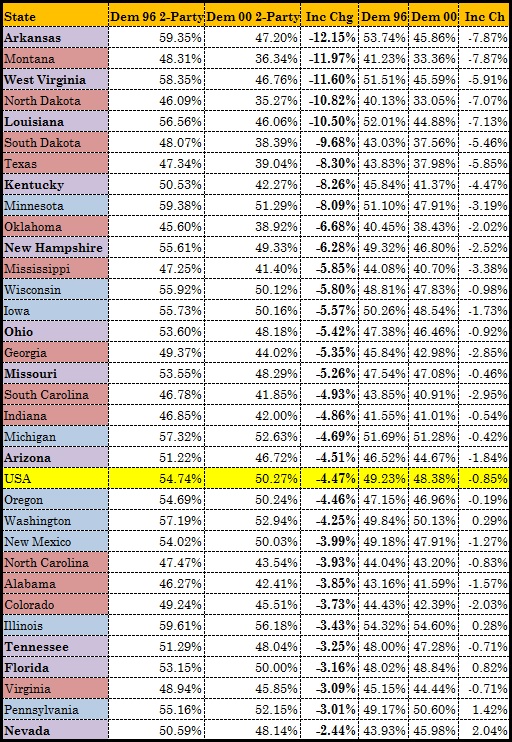

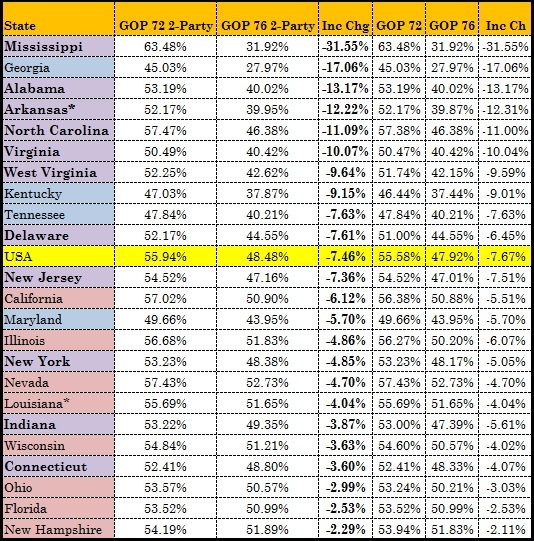

1976: The South Rises Again

Nationally, the overarching theme of the 1976 election was the hangover from Watergate and Jimmy Carter’s promise of a new politics of idealism, humility, and honesty. Demographically, Carter rode to the White House entirely on the backs of the Baby Boomers, as voters under 30 made up 32.1 percent of the electorate and supported Carter while their elders supported Ford.

Nationally, the overarching theme of the 1976 election was the hangover from Watergate and Jimmy Carter’s promise of a new politics of idealism, humility, and honesty. Demographically, Carter rode to the White House entirely on the backs of the Baby Boomers, as voters under 30 made up 32.1 percent of the electorate and supported Carter while their elders supported Ford.

But geographically, the really big story was that Carter—a Georgian, a Navy veteran, a former protege of segregationist Lester Maddox, a born-again Christian, and at least nominally a pro-lifer, with the support of “fundamentalist” leaders like Jerry Falwell—flipped the entire South away from the GOP, running the Michigan-born pro-choice Gerald Ford. Of the 16 states that shifted between 13 and 42 (!) points to the Democrats, 15—all but Hawaii, again—were Southern states or border states like Delaware and West Virginia. The smallest shift was in South Dakota, the home state of the 1972 Democratic nominee, George McGovern.

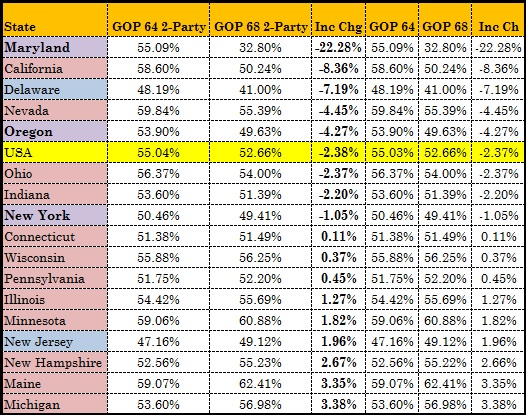

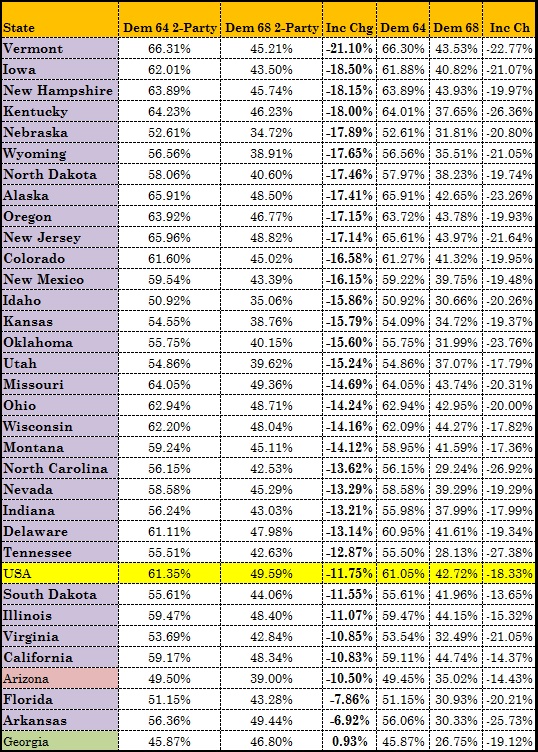

1968: The Great Society Dies In Vietnam

If you think Republicans read a lot of their own obituaries today, imagine what it was like after 1964. But even then, the size of Lyndon B. Johnson’s landslide was inflated by sympathy after the John F. Kennedy assassination and the GOP’s choice of Barry Goldwater as its candidate. Neither of those would prove an enduring basis for a coalition, and just four years later, the combination of the Vietnam War, the Great Society, the spread of unrest in inner cities and on college campuses, and the lingering discontent of the Dixiecrat faction of the Democratic Party combined to splinter LBJ’s coalition from the Left and the Right at once. Notably, the biggest shifts from LBJ ‘64 to Richard Nixon ‘68 came in rural states outside the South that have been traditionally skeptical of foreign interventions and had little use for George Wallace’s Dixiecrat campaign (Wallace got 3 percent of the vote in Vermont, 4 percent in New Hampshire, less than 6 percent in Iowa and the Dakotas). But the Wallace rebellion, which marked both the last gasp for segregationists, who had been a bedrock of the Democratic Party for over a century, also cost the Democrats, as the internal contradictions of their coalition came home to roost.

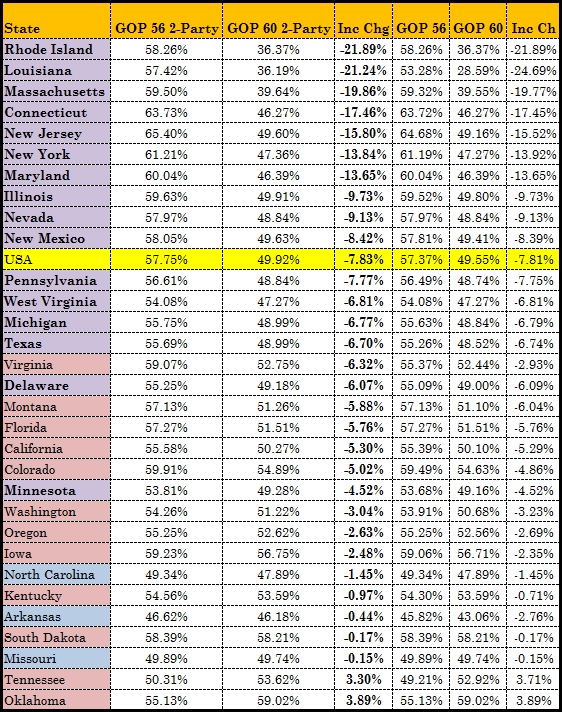

1960: We Liked Ike, But…

The 1960 election, like 2000, was conducted in the absence of the kind of dramatic events that marked 2008 or 1968, and thus is a vivid illustration of the natural tendency of the electorate to drift away from the incumbent party once a politically successful incumbent departs the scene, even when succeeded by a well-known heir apparent. It also reflects the power of religion, as the Catholic John F. Kennedy made his biggest inroads in states with large Catholic populations (mostly in the Northeast, but note how Louisiana bucked the trend of its far less Catholic neighbors). But the writing was already on the wall for the GOP when it lost fourteen Senate seats in the 1958 midterms.

The 1960 election, like 2000, was conducted in the absence of the kind of dramatic events that marked 2008 or 1968, and thus is a vivid illustration of the natural tendency of the electorate to drift away from the incumbent party once a politically successful incumbent departs the scene, even when succeeded by a well-known heir apparent. It also reflects the power of religion, as the Catholic John F. Kennedy made his biggest inroads in states with large Catholic populations (mostly in the Northeast, but note how Louisiana bucked the trend of its far less Catholic neighbors). But the writing was already on the wall for the GOP when it lost fourteen Senate seats in the 1958 midterms.

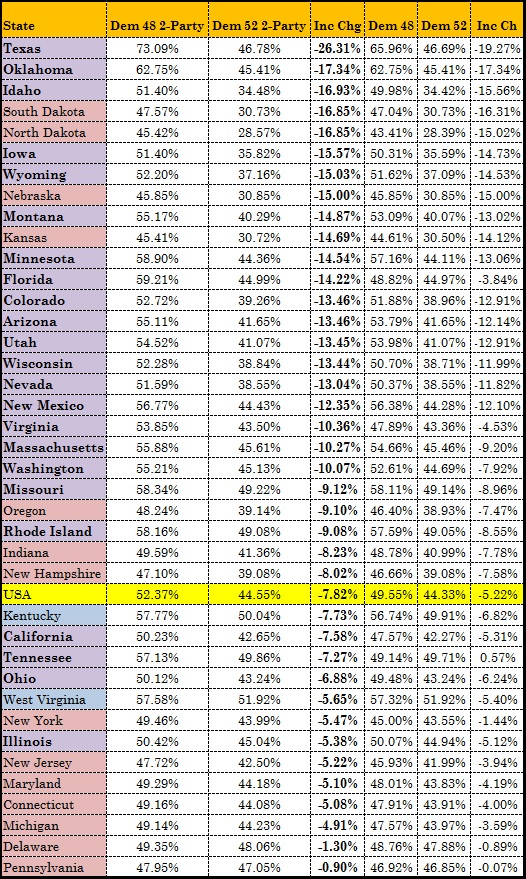

1952: The New Deal Is Not So New Anymore

Dwight Eisenhower’s 1952 victory provides the longest list of battleground states in this study, reflecting the fact that Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s massive 1936 landslide had been whittled down by 1948 to a fracturing coalition hanging on by its fingernails, but also reflecting that Ike won twelve states where Truman had carried 55 percent or more of the two-party vote in 1948. As often happens with Democratic coalitions, war was a big factor, the Korean War having raged for two years, leading Americans to turn to the victor of Normandy—who was born, but not raised, in Texas.

Dwight Eisenhower’s 1952 victory provides the longest list of battleground states in this study, reflecting the fact that Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s massive 1936 landslide had been whittled down by 1948 to a fracturing coalition hanging on by its fingernails, but also reflecting that Ike won twelve states where Truman had carried 55 percent or more of the two-party vote in 1948. As often happens with Democratic coalitions, war was a big factor, the Korean War having raged for two years, leading Americans to turn to the victor of Normandy—who was born, but not raised, in Texas.

1944-48: Dewey Does Not Defeat Truman, or FDR

1944:

These two elections need to be discussed together, because they represent a successful effort by the Democrats, first in seeking Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fourth term in the midst of World War II, and then in re-electing Harry Truman four years later, to stave off the further dissolution of the New Deal coalition after the initial shakeout of 1940 peeled off the coalition’s most tenuous supporters. But they also go together because the Republicans ran the same stiff, colorless moderate, New York prosecutor, Tom Dewey, in both elections.

These two elections need to be discussed together, because they represent a successful effort by the Democrats, first in seeking Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fourth term in the midst of World War II, and then in re-electing Harry Truman four years later, to stave off the further dissolution of the New Deal coalition after the initial shakeout of 1940 peeled off the coalition’s most tenuous supporters. But they also go together because the Republicans ran the same stiff, colorless moderate, New York prosecutor, Tom Dewey, in both elections.

FDR in 1944 actually won back one state, Michigan, that he had lost four years earlier (perhaps not coincidentally, Michigan was in the midst of a colossal defense spending boom as the whole auto industry was then occupied building tanks, jeeps, trucks, and other war materiel). The combination of war and the presence of the same old candidate on the ballot mostly froze the 1940 results in place; only four states shifted by more than 3 points. By 1948, the writing was on the wall, as the Dixiecrats bolted the party on the Right under Strom Thurmond, and the more socialistic Democrats bolted on the Left under Henry Wallace, Truman’s predecessor as vice president. Truman won back five states Dewey had carried in 1944, including Ohio, while nine states (mostly in the Northeast) slipped out of his grasp. But ultimately, the relatively small movement in the electorate is characteristic of elections with an incumbent on the ballot.

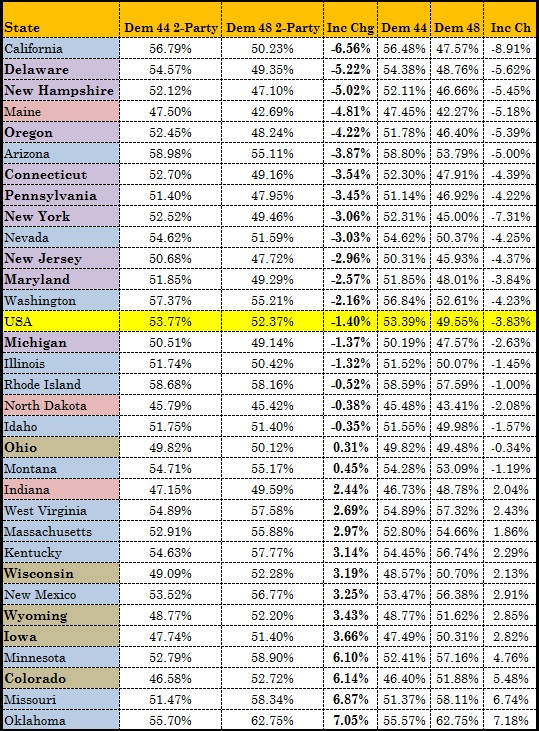

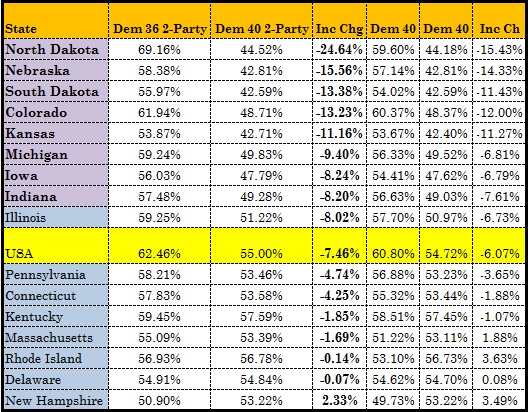

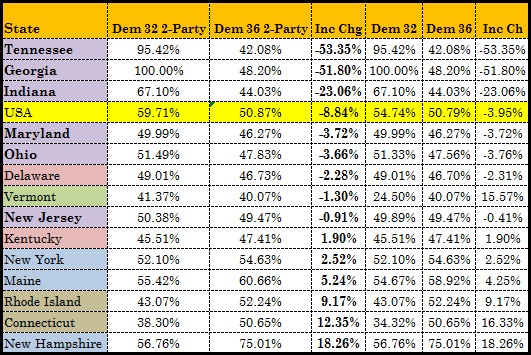

1940: Third-Term Blues

FDR’s status as the only president to serve more than two terms is partly a feature of the outbreak of war in China in 1937 and Europe in 1939 and the fall of France in 1940, all of which set America on the eve of war going into an election in which the opposing candidate, the 48-year-old novice politician Wendell Willkie, nobly refused to break with the Roosevelt administration on any serious question of foreign policy. But more broadly, it’s simply a reflection of the colossal size of Roosevelt’s 1936 landslide (62.46 percent of the two-party vote), which made it possible for him to burn off a lot of support and still have enough left to win. Which is precisely what he did: FDR carried 17 states in which his share of the two-party vote dropped by at least 7 points, and seven states in which he absorbed double-digit losses. In Wisconsin, his share of the two-party vote dropped from 67.83 to 50.93 percent, a breathtaking setback but still not enough to change the outcome.

FDR’s status as the only president to serve more than two terms is partly a feature of the outbreak of war in China in 1937 and Europe in 1939 and the fall of France in 1940, all of which set America on the eve of war going into an election in which the opposing candidate, the 48-year-old novice politician Wendell Willkie, nobly refused to break with the Roosevelt administration on any serious question of foreign policy. But more broadly, it’s simply a reflection of the colossal size of Roosevelt’s 1936 landslide (62.46 percent of the two-party vote), which made it possible for him to burn off a lot of support and still have enough left to win. Which is precisely what he did: FDR carried 17 states in which his share of the two-party vote dropped by at least 7 points, and seven states in which he absorbed double-digit losses. In Wisconsin, his share of the two-party vote dropped from 67.83 to 50.93 percent, a breathtaking setback but still not enough to change the outcome.

Typically of hubristic second terms, some of FDR’s loss of support was Republicans coming home, some was conservative Democrats tiring of the New Deal and unpopular second-term stunts like the infamous 1937 “Supreme Court-packing” plan, some was dissatisfaction over the continuing poor economy in 1937-39, and some was sentiment against any president breaking the taboo on running for a third term. But while Southern Democrats had increasingly begun opposing the New Deal in Congress, Southern voters were still unwilling to switch parties in a national election (1928 aside): FDR still won 95 percent of the two-party vote in South Carolina and Mississippi, 85 percent in Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana, 74 percent in North Carolina. It was in the upper Midwest and the Great Plains that Willkie, an Indiana native and himself a Democrat and supporter of FDR and the New Deal in FDR’s first term, flipped eight states.

(A footnote: everyone remembers that FDR died just a few months into his fourth term. But both Willkie and Willkie’s running mate, Senate Minority Leader Charles McNary, died before the next election was held).

1920: Normalcy 1, Progressivism 0

I covered the Democrats of 1920-28 already in the main article; the 1920 Republican landslide, in the first showdown since 1900 between a conservative Republican and at least the legacy of a Progressive Democrat, illustrates rather graphically how Progressive presidencies ordinarily tend to fracture their coalitions after eight years so badly that the map expands enormously in a short time (of course, their 1918 midterm wipeout had given the Democrats warning that something like this was coming). As in other years, North Dakota is high on the list of states eager to throw the bums out in favor of some new bums.

I covered the Democrats of 1920-28 already in the main article; the 1920 Republican landslide, in the first showdown since 1900 between a conservative Republican and at least the legacy of a Progressive Democrat, illustrates rather graphically how Progressive presidencies ordinarily tend to fracture their coalitions after eight years so badly that the map expands enormously in a short time (of course, their 1918 midterm wipeout had given the Democrats warning that something like this was coming). As in other years, North Dakota is high on the list of states eager to throw the bums out in favor of some new bums.

Defeat, as always, can sow the seeds of regeneration: the losing vice presidential nominee in this fiasco was Franklin D. Roosevelt, who twelve years later would bring the Democrats back to power. As for the winner, Warren G. Harding, his most lasting contribution to American politics would be his coining (or at least popularizing) of the term “Founding Fathers.”

1904-08: Teddy’s Handoff

1904:

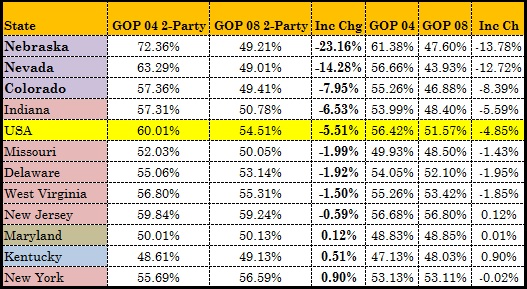

The 1908 election featured a victory for the incumbent party and a relatively narrow set of battlegrounds, but once again that owes more to the size of the coalition William Howard Taft inherited than any ability to prevent it from shrinking. The biggest shifts in 1904 and 1908 can be partly attributed to the fact that William Jennings Bryan, the Nebraska prophet of Free Silver who had been the Democrats’ nominee in 1896 and 1900, was off the ticket in 1904 but back in 1908, so Nebraska moved two points to the GOP in 1904 and 23 points back to Bryan in 1908. He also flipped the two biggest silver-mining states in 1908. As with Dewey (and Henry Clay in an earlier age), Bryan illustrates how running the same candidate over and over can blunt the tendency of voters to re-evaluate the two parties when given a fresh set of choices. As for 1904, as I noted in the main article, Teddy Roosevelt’s ability to buck the trend of campaigns following a re-election is mostly attributable to the fact that he had three years in office to build his own profile as an incumbent (as did Truman before 1948, and as Ford in 1976 did not. Neither did LBJ, but LBJ’s party was just finishing its first term in power.).

The 1908 election featured a victory for the incumbent party and a relatively narrow set of battlegrounds, but once again that owes more to the size of the coalition William Howard Taft inherited than any ability to prevent it from shrinking. The biggest shifts in 1904 and 1908 can be partly attributed to the fact that William Jennings Bryan, the Nebraska prophet of Free Silver who had been the Democrats’ nominee in 1896 and 1900, was off the ticket in 1904 but back in 1908, so Nebraska moved two points to the GOP in 1904 and 23 points back to Bryan in 1908. He also flipped the two biggest silver-mining states in 1908. As with Dewey (and Henry Clay in an earlier age), Bryan illustrates how running the same candidate over and over can blunt the tendency of voters to re-evaluate the two parties when given a fresh set of choices. As for 1904, as I noted in the main article, Teddy Roosevelt’s ability to buck the trend of campaigns following a re-election is mostly attributable to the fact that he had three years in office to build his own profile as an incumbent (as did Truman before 1948, and as Ford in 1976 did not. Neither did LBJ, but LBJ’s party was just finishing its first term in power.).

1868-76: The Rise and Fall of Reconstruction

1868:

States that had no electoral votes in 1872 due to Reconstruction are marked on the 1876 chart with an asterisk.

States that had no electoral votes in 1872 due to Reconstruction are marked on the 1876 chart with an asterisk.

Both Ulysses S. Grant in 1868 and Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876 suffered from the gradual return of post-Civil War America to ordinary politics, and the revival of the Democratic Party outside the Confederacy while the winding down of Reconstruction enabled it to regain control of the erstwhile Confederate states. As noted in the main article, Grant was in something of an atypical position for a post-incumbent, re-election candidate because Andrew Johnson was at bitter odds with the Republican Party by 1868, but typically Democratic states like Maryland and Delaware that had been near the front lines of the Civil War in 1864 (Maryland had been invaded by Robert E. Lee in 1862) were already heading back to their natural partisan homes with the war over, and some Western states were less invested in the politics of Reconstruction. By 1876, with Grant having suffered two scandal-tarred terms and the Northern public tiring of enforcing Reconstruction, the GOP’s hold weakened further, and only some highly questionable maneuvering after a popular vote loss kept Republicans in the White House.

The biggest shifts in 1876 came in Deep South states like Mississippi, where the Klu Klux Klan more or less murdered anyone who gave signs of voting Republican, but the Democrats’ strength in New York and New Jersey was also reasserting itself.

1836: You’re No Old Hickory

As a bonus, here’s the chart for the 1836 election. Whig states are marked in red, and since the Whigs ran three candidates but only one in each state (in a bizarre bid to throw the election to the Democrat-controlled House), I computed the national two-party vote not only against their main candidate, William Henry Harrison, but against the totals of Harrison, Hugh White, and Daniel Webster, and compared Martin Van Buren to whichever candidate the Whigs ran in that state. They actually also ran a fourth candidate, Willie Magnum, in South Carolina, but South Carolina did not select presidential electors by popular vote until after the Civil War—it was the last holdout against the popular vote. Vermont was won in 1832 by the third-party anti-Masonic candidate.

As a bonus, here’s the chart for the 1836 election. Whig states are marked in red, and since the Whigs ran three candidates but only one in each state (in a bizarre bid to throw the election to the Democrat-controlled House), I computed the national two-party vote not only against their main candidate, William Henry Harrison, but against the totals of Harrison, Hugh White, and Daniel Webster, and compared Martin Van Buren to whichever candidate the Whigs ran in that state. They actually also ran a fourth candidate, Willie Magnum, in South Carolina, but South Carolina did not select presidential electors by popular vote until after the Civil War—it was the last holdout against the popular vote. Vermont was won in 1832 by the third-party anti-Masonic candidate.

Van Buren’s biggest falloff by far was in Andrew Jackson’s home state of Tennessee and other Southern states where Henry Clay had not even competed in 1832. By contrast, New Yorker Van Buren improved on Jackson in New York and several states in the Northeast where the rough-hewn frontiersman and his crusade against Eastern bankers had not played as well.