In Elysium, one of the more notable box office failures in a disastrous summer for Hollywood, Matt Damon plays a down-on-his-luck ex-con in a dystopian future in which overpopulation, natural resource depletion, and environmental degradation have led to a worldwide economic collapse. In response, the world elite have decamped to a life of luxury on an orbital space station.

If this all sounds a bit familiar, it might be because the same basic setting is behind the plot of the 2008 Pixar film Wall-E, which is also set in a future in which environmental degradation has led the earth’s population to abandon earth for a luxury-liner style spaceship. In that film, a lovable animated robot teaches us that overconsumption is damaging to our basic humanity.

Also crash landing at the cineplex this summer was Will Smith and M. Night Shyamalan’s After Earth, in which an environmental catastrophe leads humanity to abandon earth for a new planet in another solar system.

Sometimes, of course, the situation is reversed. In Man of Steel, it is Krypton that ends up destroyed through natural resource depletion, forcing Jor-El to send his son to safety on planet earth. And in Pacific Rim alien monsters seek to take over earth after they have made their own planet uninhabitable.

Even when not making movies, Hollywood has overpopulation on the brain. During the 2012 campaign, Joss Whedon issued a satirical video “endorsement” of Mitt Romney. According to Whedon, Romney’s policies would lead to “poverty, unemployment, overpopulation, disease, rioting” and ultimately help bring about the zombie apocalypse, which Whedon satirically supported.

Thomas Malthus: Script-Doctor

Where is Hollywood getting this stuff? The answer, improbably enough, is that they are getting it from the 18th Century Anglican Priest and economist Thomas Malthus. In his 1798 work An Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus argued that, if left to its own devices, human population growth would outstrip improvements in agricultural productivity, leading inevitably to war, famine, pestilence, and death.

History has not been kind to Rev. Malthus’ arguments. Shortly after the book first appeared, the Industrial Revolution began and living standards began rapidly increasing even as the world’s population exploded. And while there were periodic warnings that we were about to run out of coal, or oil, or some other vital resource, these predictions were largely ignored, and ultimately proved false.

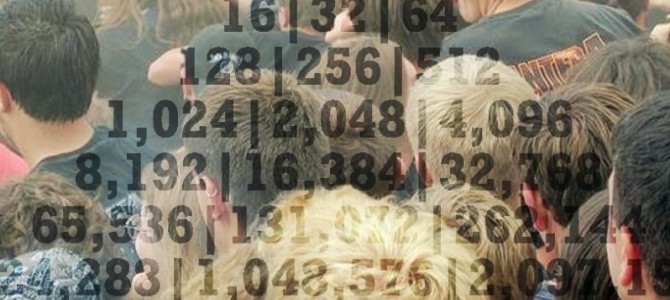

Starting in the mid-1960s, Malthusian fears began a strange rebirth. In his 1968 book, The Population Bomb, Paul Ehrlich relied on Malthus’ theories to argue that overpopulation would inevitably lead to disaster. “The battle to feed all of humanity is over,” Ehrlich wrote. “In the 1970’s the world will undergo famines–hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” The situation was so dire Ehrlich even went so far as to say that “[i]f I were a gambler, I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000.” This, mind you, in a work that was purportedly non-fiction, not science fiction.

Ehrlich wasn’t alone. In 1972 the prestigious Club of Rome published The Limits to Growth, a report predicting that the world would run out of various commodities within 40 years. Ehrlich was a frequent guest on “The Tonight Show,” where he propounded his theories to a sympathetic Johnny Carson. Political figures as diverse as Richard Nixon and Martin Luther King, Jr. began to speak about the “population problem.” Even the normally clear-headed Alexander Solzhenitsyn uncritically accepted the Club of Rome’s predictions in his 1974 open letter to the Soviet leadership.

It was only natural that these dire predictions would start to work their way into film. People today remember the 1973 film Soylent Green chiefly for an over-the-top scene in which Charlton Heston reveals Soylent Green’s secret ingredient. But the film is really about a dystopian future in which (you guessed it) overpopulation and natural resource depletion have forced governments to resort to euthanasia and cannibalism. In Logan’s Run, humanity manages to overcome the population problem via a grim bargain: people live the high life until their 30th birthday, at which point they are summarily executed.

In reality, government action to fight overpopulation tended to be directed not towards the old but against the young. In India, Sanjay Gandhi, son of then-dictator Indira Gandhi, headed up a government program of mass forced sterilizations. According to official statistics, 1,774 people were killed by botched medical operations that were part of the program. The Communist government of China imposed its One Child Policy in an attempt to stem the tide of population growth.

As a democracy, the United States was largely spared coercive population control measures, though American money and Western organizations such as the World Bank and Ford Foundation and supported those efforts in the developing world. Still, just as Ehrlich’s theories gained currency, Americans were enduring forced rationing, gas lines, and Jimmy Carter. Our malaise was frequently cited as proof of Malthusianism.

The Population Bomb Fizzles

But a funny thing happened on the way to the apocalypse. Instead of running out of natural resources, they got cheaper. Population growth led to economic growth, not economic collapse. In the 1966 novel on which Soylent Green was based, earth’s population in the year 2022 has reached the staggering level of… seven billion. In other words, the book actually underestimated world population growth. Yet from 1961 to 2007, the food supply increased 27 percent per person, despite world population growing from 3.6 to 6.7 billion.

The real problem with the panicked predictions of Soylent Green and The Population Bomb was a failure of imagination combined with a lack of faith in the creativity and resilience of humanity. Predictions of imminent resource exhaustion based on currently known supplies is the equivalent of going to your local supermarket, calculating that there is only enough food there to last a couple of weeks, and concluding that we should see mass starvation by the end of the month. The math behind the calculations might be fine, but the inability to take into account human adaptability makes them nearly worthless.

Ehrlich’s strongest critic was the economist Julian Simon, and Ehrlich proved to be enough of gambler to make a public bet with Simon. In 1980, Simon argued that, contra Ehrlich’s doomsaying, commodities would become more plentiful and cheaper over the next decade. As Simon saw things, it was a mistake to think of natural resources as finite materials in the ground. Throughout most of history, having oil on your land was kind of a nuisance. It’s black and sticky and wasn’t good for much of anything. It’s only when people figured out some valuable use for oil that it became a natural resource. Human ingenuity, therefore, is the ultimate resource. More people means not just more consumers, but more problem solvers.

In 1990, Ehrlich was forced to admit his predictions were wrong and mailed Simon a check for losing the bet. You’d think that realizing mass starvation was not inevitable would have been a relief, but Ehrlich was hardly a gracious loser. If someone had to die in order to prove scarcity and overpopulation were legitimate concerns, Ehrlich had an idea about who that might be. Five years after losing his bet, he would tell the Wall Street Journal, “If Simon disappeared from the face of the Earth, that would be great for humanity.”

Back to Hollywood

Why, then, are so many of today’s movies wrapped up in something as thoroughly discredited as Malthusianism? Well, liberal people will tend to make liberal movies espousing liberal causes, so the fact that liberal-dominated Hollywood gravitates to environmental themes is not so surprising. But there might also something deeper going on.

In The Population Bomb, Ehrlich writes of a formative experience he had during a taxi ride in Dehli on a hot summer night:

The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to the buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people.

Ehrlich’s conclusion from all this was that the world had “too many people.” But just below the surface of his description is the idea that the problem is not just too many people, but too many of the wrong kind of people. It’s not a coincidence that concern about overpopulation really got going after birth rates had fallen in the developed world. P.J. O’Rourke summed up this thinking behind the population control movement aptly: “Just enough of me, way too much of you.”

There’s a parallel dynamic involved when it comes to Hollywood. The gulf between the lifestyle of a Hollywood superstar and, say, a grocery clerk in Wichita, might not be as great as that between Paul Ehrlich and an Indian beggar, but it’s still pretty big. For Hollywood superstars, living high on the hills above and away from the mass of ordinary people might not quite be living on an orbital space station, but it might feel that way. “People have asked me if I think this is what will happen in 140 years,” Elysium’s director Neill Blomkamp said in a recent interview. “But this isn’t science fiction. This is today. This is now.”

Despite the huge sums made in the modern media, there is also a sense of precariousness and foreboding in much of the industry. New technology, digital piracy, and changing viewing habits, all threaten to undermine the current Hollywood hierarchies. This past June Steven Spielberg warned that Hollywood’s exorbitant profit margins were not to be taken for granted. “There’s going to be an implosion where three or four or maybe even a half-dozen mega-budget movies are going to go crashing into the ground, and that’s going to change the paradigm,” he said. It would prove prophetic. This year’s summer blockbuster season has been defined by a slew of big-budget flops including Elysium, Pacific Rim, After Earth, The Lone Ranger, R.I.P.D., and White House Down. Already studios are talking about “changing the paradigm.” Maybe it’s not environmental disaster, but emotionally it is close enough for the industry to seize on environmental metaphors to express their anxiety that the world as they know it is ending.

A Simonian Cinema

You would think that Julian Simon’s message of the importance of human creativity would appeal to Hollywood. Movies themselves, after all, are an amazing example of the powers of human ingenuity in action.

Consider Gattaca, a film set in a future where an ideology of genetic determinism has led to a hide-bound view of human limitations, and enforced by the government. The film is a brilliant depiction of how individual determination and creativity can overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles. And more than a decade and a half later, the film still holds up (something I doubt will be said of Elysium, let alone After Earth).

But Gattaca is only one example. The late 1990s asteroid movies, Armageddon and Deep Impact show humanity defying the heavens and using ingenuity to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds. Movies from The Edge to Swiss Family Robinson show man surviving in a harsh environment. And It’s a Wonderful Life’s demonstration of the positive impact individuals have on the community has spawned countless imitators.

The optimism of Julian Simon can and should serve as a more fruitful source of artistic inspiration than the unfactual doom and gloom of Malthus and Ehrlich. A film or two embodying Simon’s optimism about human potential might make some money, which is more than you can say for a lot of recent pictures. But to do that, many screenwriters, directors, and producers will have to give up on recycling the same tired old Malthusian clichés.