An outlandish theory that Donald Trump was a traitor who had conspired with Russia to steal the 2016 election gripped much of the nation’s media for more than two years. Countless “bombshells” in support of this theory were published and broadcast. Media outlets won numerous awards for publishing leaks they received from partisan government officials and other operatives.

When Special Counsel Robert Mueller announced in late March that his sprawling Russia probe had ended with not a single indictment related to criminal collusion, it was a devastating blow to the media’s already damaged credibility. “The Mueller Report is an unmitigated disaster for the American press and the ‘expert’ class that it promotes,” wrote Lee Smith in an overview at The Tablet. Smith was one of the exceedingly small handful of journalists who didn’t fall for the Russia conspiracy.

I’ve written dozens of stories skeptical of the Russia-Trump conspiracy and critical of the media’s coverage of it. How were a few of us able to resist the overwhelming pressure to join the conspiracy theorists?

My Week as a Russia Truther

I joke that I actually began as a Russia truther. It’s not quite right, but I certainly noticed that Russian social media accounts were behind the troll armies on Twitter that would complain if you criticized Donald Trump. The June 2015 New York Times article on the massive Russian troll armies made me realize that Russians were active and engaged in chaos operations.

I noticed some Russian social media accounts engaging in general shenanigans, too. For example, after the December 2015 terrorist shooting in Sen Bernardino, a Russian-connected account claimed that the name of one of the shooters was very similar to the name of the Turkish president. I’d also been subjected to other harassment from what I believed to be Russian-connected individuals.

I initially found Trump’s candidacy a bit befuddling. Until he officially filed paperwork, I had ignored him. Then I wrote some pieces that were favorable and some that were critical. As his candidacy continued to gain momentum, however, I got extremely anxious. I realized he was likely going to win the presidency in January 2016, and I was not happy about it. I had no expectation he’d govern as a conservative. I actually had meetings with people I trusted, and spent months trying to come to terms with the reality that he was going to be the Republican nominee. Yes, I was largely surrounded by NeverTrumpers at this time.

All of that is to explain that when a list of foreign policy advisors was released on March 21, 2016, I completely fell for the spin that they had troubling ties to Russia. I researched stories claiming as much and found that some of them did seem pretty close to Russia.

I went to an Easter party the next week, and was loudly explaining my Trump-Russia conspiracy theory to a few friends, including one who happened to know Carter Page, one of the men I was talking about. He patiently explained to me that I was all wet, and that Page merely had a different foreign policy from the one espoused by much of the Washington D.C. blob.

My acquaintance — who had an illustrious military and public service career — wasn’t on board with Page’s ideas, but he was extremely critical of the consensus that had formed in D.C. around such issues as NATO expansion, U.S. obligations in the region, and the unchecked rise of China. He helped me realize that I was buying a bit too much into the consensus, a lesson I kept having to learn over the next few months.

Media Rejects Its Own Standards

I saw more and more pundits fail to understand Trump’s non-interventionist foreign policy and how it related to his success in the Republican primary and, later, the general campaign.

In late July, while the media continued to run interference for Hillary Clinton, Trump declined to play along. Clinton had set up a private server for government business, and when investigated for it, she deleted 30,000 emails that she claimed were personal then destroyed the server while under investigation.

The private server was a prime target for foreign hacking, and Trump joked at a press conference that if Russia had those 30,000 deleted emails from the now-destroyed server, they should share them with the world. Immediately the media pretended, all evidence to the contrary, that he’d been calling on Russia to hack some current server that housed current Clinton emails.

The Russia hysteria was ramping up. Paul Manafort was forced to resign as campaign chairman in August 2016 after negative stories about his time doing campaigns in Ukraine for pro-Russian factions. Clinton allies had worked on the other side of that fight in Ukraine.

That same August, New York Times media reporter Jim Rutenberg said if reporters believe Trump is as bad as his worst critics claim, then they had to “throw out the textbook American journalism has been using for the better part of the past half-century” and become “oppositional” against him. Among the reasons cited for throwing out journalistic standards was that Trump thought NATO countries should take their defense budgets more seriously.

New York Times reporters threw out the textbook, as did many others, as they claimed Trump’s rejection of the country’s previous few decades of interventionist wars was dangerous, unprecedented, and tremendously alarming. I remembered how the same media had loathed Mitt Romney for saying Russia was the country’s primary geopolitical foe. The media’s views on Russia changed dramatically based on what the Republican candidate was saying about the country and its leadership. It made me more skeptical of their coverage of the matter.

Watching Information Operations In Action

In late September, I watched a perfectly executed information operation play out from the Clinton campaign. It was the campaign’s opposition research on women, hooked to Alicia Machado. These things can only roll out perfectly thanks to a compliant media, one thing the Clinton campaign had in spades.

In late October, I watched another attempted information operation roll out from the Clinton campaign. It was opposition research related to Trump and Russia. I noticed that when the stories dropped, the typically slow Clinton immediately put details about one of them at the top of her Twitter feed and pinned them.

It was a curious move, and made me think her involvement in that story was even more than I already suspected. And I already suspected it was her campaign that was peddling the information. It is perhaps worth noting that the story — about a mysterious server pinging Russia from Trump Tower — was debunked within hours.

When Trump won the 2016 election, it shocked most of the elites who control discourse. An excerpt from “Shattered,” a book about the 2016 Clinton campaign, explained what happened next:

In other calls with advisers and political surrogates in the days after the election, Hillary declined to take responsibility for her own loss. ‘She’s not being particularly self-reflective,’ said one longtime ally who was on calls with her shortly after the election. Instead, Hillary kept pointing her finger at Comey and Russia. ‘She wants to make sure all these narratives get spun the right way,’ this person said.

That strategy had been set within twenty-four hours of her concession speech. Mook and Podesta assembled her communications team at the Brooklyn headquarters to engineer the case that the election wasn’t entirely on the up-and-up. For a couple of hours, with Shake Shack containers littering the room, they went over the script they would pitch to the press and the public. Already, Russian hacking was the centerpiece of the argument.

In Brooklyn, her team coalesced around the idea that Russian hacking was the major unreported story of the campaign, overshadowed by the contents of stolen e-mails and Hillary’s own private-server imbroglio.

The Clinton strategy wasn’t reported for a few months, but it was obvious to any mildly observant onlooker. Reporters followed Clinton’s lead, per usual, and fixated on Russia. The Obama administration published a couple of reports making the case for the seriousness of Russian meddling that some cyber experts dismissed as not well substantiated.

The Russia Narrative as Refusal to Accept Reality

Around this time I began doing a bit more post-election analysis on television. I noticed that the Russia narrative was increasingly being clung to as an explanation for the media’s failures to understand the country they purport to cover. I pushed back against the idea that the American people had been duped by “fake news” (which then meant something else entirely, we might remember) or “Russia” when they voted for Trump, even if such a vote was obviously unfathomable to most media figures.

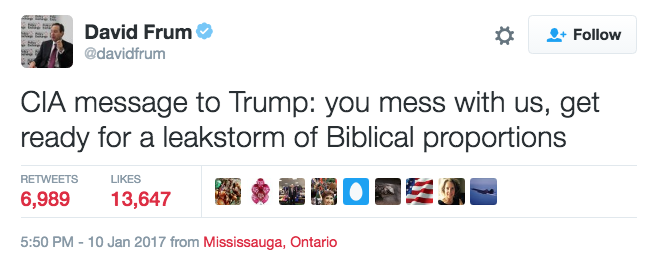

The Russia strategy Clinton had deployed was being picked up by Obama’s intelligence agencies and spread far and wide by American media, and it annoyed Trump. When he’d dismiss the fevered theories that Russian meddling was the reason Hillary Clinton had failed to visit the upper Midwest, intelligence analysts responded by threatening him with leaks.

Here’s how former George W. Bush speechwriter and Resistance leader David Frum put it:

It was into this craziness that CNN published their story on January 10, 2017, headlined “Intel chiefs presented Trump with claims of Russian efforts to compromise him.” Here are the first two paragraphs of the article written by Evan Perez, Jim Sciutto, Jake Tapper, and Carl Bernstein (Carl Bernstein was recently named as one of the dozen journalists who received a copy of the dossier from Sen. John McCain associate David Kramer. And Jim Sciutto was previously employed as a senior advisor in the Obama administration.):

Classified documents presented last week to President Obama and President-elect Trump included allegations that Russian operatives claim to have compromising personal and financial information about Mr. Trump, multiple US officials with direct knowledge of the briefings tell CNN.

The allegations were presented in a two-page synopsis that was appended to a report on Russian interference in the 2016 election. The allegations came, in part, from memos compiled by a former British intelligence operative, whose past work US intelligence officials consider credible. The FBI is investigating the credibility and accuracy of these allegations, which are based primarily on information from Russian sources, but has not confirmed many essential details in the memos about Mr. Trump.

This was the story that poured gasoline on Clinton’s incendiary Russia narrative.

Being More Than a Leak Receptacle

CNN received an award for publishing this leak from a top-level intelligence official. At best they were far too credulous of this leak. At worst, they knowingly took part in an information campaign designed to hurt Trump. Neither option is particularly good.

Yes, Obama intel leaders briefed the presidents on the completely unverified claims, but the real story was that they were so bad at their jobs that they were playing around with these claims in the first place. The real story was that they were leaking that they’d briefed the dossier so that it would legitimize the claims and undermine the duly elected president who was to succeed Obama.

The real story, we’d later find out thanks to dogged investigations by a few Republicans in the House and Senate, was that the claims were bought and paid for by the Clinton campaign and Democratic National Committee. The real story, we’d find out later, was that these unverified claims had been used to secure wiretaps on Carter Page, an innocent American citizen affiliated with the Trump campaign. The real story was that our media were too busy “throwing out” journalistic standards that they forgot to hold powerful law enforcement and intelligence agencies accountable.

I didn’t fall for the Russia hoax that CNN and other media outlets did because I worked hard at understanding the appeal of his candidacy even before the Russia narrative started. At the same time, I recognized how disruptive he was to the established order and the livelihoods of those who had grown comfortable in D.C. Unlike many reporters, I knew and loved many people who voted for Trump. My background as a media critic made me aware of information campaigns and how to resist them. My dislike of the interventionist foreign policy made me less susceptible to scaremongering about realist foreign policy.

Also, I believed intelligence agencies when they claimed they would selectively leak against Trump as retaliation for his criticism of them, and knew to be skeptical of anonymous leaks. It helped that someone inadvertently revealed some information to me about the source of the information CNN had been given.

It wasn’t just about not falling for the fake conspiracy theory. If Trump was not what all the media outlets long suggested he was — a traitor who was conspiring with Russia — that meant that he was the victim of an information operation that was being funneled through the highest powers of the federal government.

Because a few of us weren’t so foolish to fall for the first theory, we were able to look at the leak operation that gullible media outlets were engaged in with a more critical eye.