“Today, the men and women of the NRA honor the profound life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,” the gun-rights group National Rifle Association tweeted on Martin Luther King Day. “King applied for a concealed carry permit in a ‘may issue’ state and was denied. We will never stop fighting for every law-abiding citizen’s right to self-defense.”

The tweet triggered widespread anger and condemnation from liberals, most of them pointing out that King was murdered by a gun. Just as guns themselves are not evil, they are not a panacea. Yet, whether intentional or not, strict gun control laws are often functionally racist. They deny the most vulnerable citizens in our communities, people who reside in urban liberal areas — in cities like Chicago and DC — the right to defend themselves, their families, and their property from criminality.

King, who remained the target of unceasing violent threats throughout his life, often relied on armed guards to protect his home and family. While King left no detailed position on the Second Amendment, he did indeed apply for a concealed carry permit after his house had been firebombed in 1956. Almost surely because of the color of his skin, Alabama law enforcement denied his application as “unsuitable.”

King’s inability to arm himself was merely another episode in a long history of attacks on the rights of African Americans. While early Americans often denied both Catholics and other intolerable Christian denominations their right to self-defense, black Americans were deprived of these rights for centuries longer. Many African-Americans are denied those rights today.

The early Americans had seen the right to bear arms as a means to counteract internal tyranny and the threat of invasion. African Americans understood those threats better than most. It was the abolitionist and champion of individual rights Frederick Douglass who reacted to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, authorizing local governments to seize and return escaped slaves to their owners, by editorializing that the best remedy might be “a good revolver, a steady hand, and a determination to shoot down any man attempting to kidnap … Every slave hunter who meets a bloody death in this infernal business is an argument in favor of the manhood of our race.”

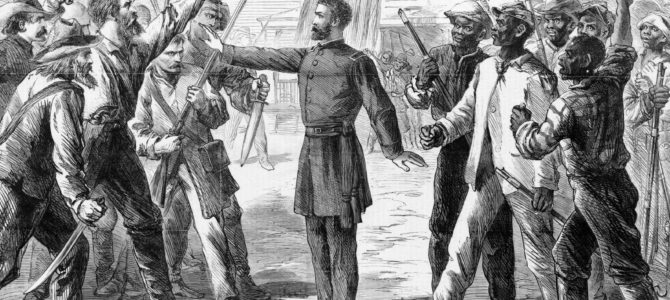

By the first post–Civil War election in 1868, some southern blacks had begun to arm themselves. In one incident in Tennessee, by brandishing his gun a black man fought off a mob of terrorizing Klansmen who dragged him from his house. “I prevented [one of them] by my pistol, which I cocked, and he jumped back,” the man explained. “I told them I would hurt them if they got away. They did not burn nor steal anything, nor hurt me.”

This event was the exception for a population that was often left helpless. “Black Codes” would soon be instituted, making the ownership of guns illegal for most blacks, leaving them at mercy of their racist neighbors and governments. This is why Jacob Howard, the Michigan senator who introduced the Fourteenth Amendment to ensure that blacks in the South had their constitutional rights protected, noted that the amendment was meant to ensure “the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendment to the Constitution” as in the freedom of speech and of the press and “the right to bear arms,” specifically.

Although some of the Founders never intended for the Second Amendment to protect all men, civil rights activists made the argument that those natural rights should extend to everyone. The late nineteenth-century civil rights leader Ida B. Wells noted that one of the lessons of post–Civil War America and “which every Afro American should ponder well,” is that “a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.” T. Thomas Fortune, another black civil rights activist of the era, argued that it was with a Winchester that the black man could “defend his home and children and wife.”

In contemporary times, African Americans helped codify the Second Amendment as an individual right. Although many people are familiar with the name Dick Heller, one of the first plaintiffs of the case that evolved into 2008’s District of Columbia v. Heller decision that codified the Second Amendment as an individual right, an African-American single woman and Washington D.C. resident named Shelly Parker was one of the first plaintiffs to sign onto the case.

Fed up with the crime near her Capitol Hill home, Parker attempted to clean up the neighborhood, provoking the ire of local drug dealers, who began vandalizing her property and threatening her life. In Washington, DC, however, if Parker obtained a gun to protect herself, she would be arrested. “In the event that someone does get in my home,” she explained, “I would have no defense, except maybe throw my paper towels at them.”

It was Otis McDonald, a 76-year-old African-American retired maintenance engineer, whose name is on landmark Supreme Court McDonald v. City of Chicago decision, which compelled that city to allow citizens to have firearms in their homes for self-defense.

This isn’t merely about bump stocks or other ancillary gun questions. Many major cities effectively ignore the Second Amendment victories of Heller and McDonald. Today numerous new gun regulations that inhibit the right of citizens in high-crime areas to defend themselves are being contemplated and voted on by politicians in cities and states across the country. Whether they find the idea of citizens defending themselves “unsuitable” or not, we do not know. What we do know is that those who most need their constitutional right to bear arms are the ones who suffer.