The New York Times’ 4,000-word report last week on the Federal Bureau of Investigation probe of Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign’s possible ties to Russia revealed for the first time that the investigation was called “Crossfire Hurricane.”

The name, explains the paper, refers to the Rolling Stones lyric “I was born in a crossfire hurricane,” from the 1968 hit “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” Mick Jagger, one of the songwriters, said the song was a “metaphor” for psychedelic-drug induced states. The other, Keith Richards, said it “refers to his being born amid the bombing and air raid sirens of Dartford, England, in 1943 during World War II.”

Investigation names, say senior U.S. law enforcement officials, are designed to refer to facts, ideas, or people related to the investigation. Sometimes they’re explicit, and other times playful or even allusive. So what did the Russia investigation have to do with World War II, psychedelic drugs, or Keith’s childhood?

The answer may be found in the 1986 Penny Marshall film named after the song, “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” In the Cold War-era comedy, a quirky bank officer played by Whoopi Goldberg comes to the aid of Jonathan Pryce, who plays a British spy being chased by the KGB.

The code name “Crossfire Hurricane” is therefore most likely a reference to the former British spy whose allegedly Russian-sourced reports on the Trump team’s alleged ties to Russia were used as evidence to secure a Foreign Intelligence Service Act secret warrant on Trump adviser Carter Page in October 2016: ex-MI6 agent Christopher Steele.

Helping Spin a New Origin Story

It is hardly surprising that the Times refrained from exploring the meaning of the code name. The paper of record has apparently joined a campaign, spearheaded by the Department of Justice, FBI, and political operatives pushing the Trump-Russia collusion story, to minimize Steele’s role in the Russia investigation.

After an October news report showed his dossier was funded by the Clinton campaign and Democratic National Committee, facts that further challenged the credibility of Steele’s research, the FBI investigation’s origin story shifted.

In December, The New York Times published a “scoop” on the new origin story. In the revised narrative, the probe didn’t start with the Steele dossier at all. Rather, it began with an April 2016 meeting between Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos and a Maltese professor named Joseph Mifsud. The professor informed him that “he had just learned from high-level Russian officials in Moscow that the Russians had ‘dirt’ on Mrs. Clinton in the form of ‘thousands of emails.’”

Weeks later, Papadopoulos boasted to the Australian ambassador to London, Alexander Downer, that he was told the Russians had Clinton-related emails. Two months later, according to the Times, the Australians reported Papadopoulos’ boasts to the FBI, and on July 31, 2016, the bureau began its investigation.

Further reinforcement of the new origin story came from congressional Democrats. A January 29 memo written by House Intelligence Committee minority staff under ranking member Rep. Adam Schiff further distances Steele from the opening of the investigation. “Christopher Steele’s raw reporting did not inform the FBI’s decision to initiate its counterintelligence investigation in late July 2016. In fact, the FBI’s closely-held investigative team only received Steele’s reporting in mid-September.”

Last week’s major Times article echoes the Schiff memo. Steele’s reports, according to the paper, reached the “Crossfire Hurricane team” “in mid-September.”

Yet the new account of how the government spying campaign against Trump started is highly unlikely. According to the thousands of favorable press reports asserting his credibility, Steele was well-respected at the FBI for his work on a 2015 case that helped win indictments of more than a dozen officials working for soccer’s international governing body, FIFA. In July 2016, Steele met with the agent he worked with on the FIFA case to show his early findings on the Trump team’s ties to Russia.

The FBI took Steele’s reporting on Trump’s ties to Russia so seriously it was later used as evidence to monitor the electronic communications of Trump campaign adviser Carter Page. But, according to Schiff and the Times, the FBI somehow lost track of reports from a “credible” source who claimed to have information showing that the Republican candidate for president was compromised by a foreign government. That makes no sense.

The code name “Crossfire Hurricane” is further evidence that the FBI’s cover story is absurd. A reference to a movie about a British spy evading Russian spies behind enemy lines suggests the Steele dossier was always the core of the bureau’s investigation into the Trump campaign.

Was Halper an Informant, Spy, Or Agent Provocateur?

Taken together with the other significant revelation from last Times story, the purpose and structure of Crossfire Hurricane may be coming into clearer focus. According to the Times story: “At least one government informant met several times with [Trump campaign advisers Carter] Page and [George] Papadopoulos, current and former officials said.”

As we now know, the informant is Stefan Halper, a former classmate of Bill Clinton’s at Oxford University who worked in the Nixon, Ford, and Reagan administrations. Halper is known for his good connections in intelligence circles. His father-in-law was Ray Cline, former deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Halper is also reported to have led the 1980 Ronald Reagan campaign team that collected intelligence on sitting U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s foreign policy.

So what was Halper doing in this instance? He wasn’t really a spy (a person who is generally tasked with stealing secrets) or an informant (a person who provides information about criminal activities from the inside). Rather, it seems he was more like an agent provocateur, whose job was to ask leading questions to get Trump campaign advisers to say things that would corroborate—or seem to corroborate—evidence that the bureau believed it already had in hand.

Halper met with at least three Trump campaign advisers: Sam Clovis, Page, and George Papadopoulos. The latter two he met with in London, where Halper had reason to feel comfortable operating.

Halper’s close contacts in the intelligence world weren’t limited to the CIA. They also include foreign intelligence officials like Richard Dearlove, the former head of the United Kingdom’s foreign intelligence service, MI6. According to a Washington Times report, Halper and Dearlove are partners in a UK consulting firm, Cambridge Security Initiative.

Dearlove is also close to Steele. According to the Washington Post, Dearlove met with Steele in the early fall of 2016, when his former charge shared his “worries” about what he’d found on the Trump campaign and “asked for his guidance.”

London was therefore the perfect place for Halper to spring a trap — outside the direct purview of the FBI, but on territory where he knew he could operate safely. It appears Halper’s job was to induce inexperienced Trump campaign figures to say things that corroborated the 35-page series of memos written by Steele—the centerpiece of the Russiagate investigation—in order to license a broader campaign of government spying against Trump and his associates in the middle of a presidential election.

Halper Reached Out to Trump Campaign Members

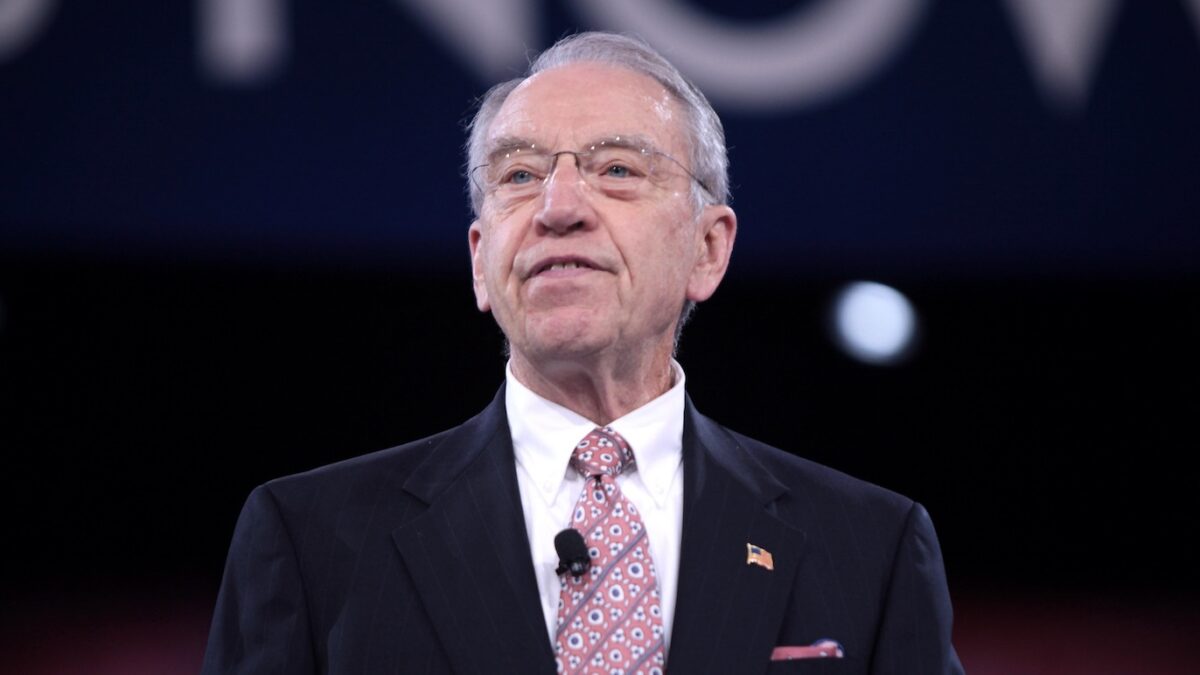

Chuck Ross’s reporting in The Daily Caller provides invaluable details and insight. As Ross explained in The Daily Caller back in March, Halper emailed Papadopoulos on September 2, 2016 with an invitation to write a research paper, for which he’d be paid $3,000, and a paid trip to London. According to Ross, “Papadopoulos and Halper met several times during the London trip,” with one meeting scheduled for September 13 and another two days later.

Ross writes: “According to a source with knowledge of the meeting, Halper asked Papadopoulos: ‘George, you know about hacking the emails from Russia, right?’ Papadopoulos told Halper he didn’t know anything about emails or Russian hacking.” It seems Halper was looking to elaborate on the claims made in Steele’s September 14 dossier memo: “Russians do have further ‘kompromat’ on CLINTON (e-mails) and considering disseminating it.”

Had Papadopoulos confirmed that a shadowy Maltese academic had told him in April about Russians holding Clinton-related emails, presumably that would have entered the dossier as something like, “Trump campaign adviser PAPADOPOULOS confirms knowledge of Russian ‘kompromat.’”

Another Trump campaign adviser Halper contacted was Page. They first met in Cambridge, England at a July 11, 2016 symposium. Halper’s partner Dearlove spoke at the conference, which was held just days after Page had delivered a widely reported speech at the New Economic School in Moscow. According to another Ross article reporting on Page and Halper’s interactions, the Trump adviser “recalls nothing of substance being discussed other than Halper’s passing mention that he knew then-campaign chairman Paul Manafort.”

Page and Manafort both figure prominently in the Steele dossier’s July 19 memos. According to the document, Manafort “was using foreign policy advisor, Carter PAGE, and others as intermediaries.” Page had also, according to the dossier, met with senior Kremlin officials—a charge he later denied in his November 2, 2017 testimony before the House Intelligence Committee. Evidently, he also gave Halper nothing to use in verifying the charges made against him.

Halper’s fishing expedition therefore came up with nothing to suggest the Steele dossier was true. The real story is therefore the continuing attempt to assert that the dossier, or key parts of it, are true, after large-scale investigations by the FBI, and now by special counsel Robert Mueller, have failed to turn up any evidence of a plot hatched between Trump and Vladimir Putin to take over the White House.

Using Spy Powers on Political Opponents Is a Big Problem

That portions of the American national security apparatus would put their considerable powers—surveillance, spying, legal pressure—at the service of a partisan political campaign is a sign that something very big is broken in Washington. Our Founding Fathers would not be surprised to learn that the post-9/11 surveillance and spying apparatus built to protect Americans from al-Qaeda has now become a political tool that targets Americans for partisan purposes. That the rest of us are surprised is a sign that we have stopped taking the U.S. Constitution as seriously as we should.

The damage done to the American press is equally large. Since the November 2016 presidential election, a financially imperiled media industry gambled its remaining prestige on Russiagate. Yet after nearly a year and a half filled with thousands of stories feeding the Trump-Russia collusion conspiracy, last week still represented a landmark moment in American journalism. The New York Times, which proudly published the Pentagon Papers, provided cover for an espionage operation against a presidential campaign.

There are significant errors and misrepresentations in the article that the Times could’ve easily checked, if it weren’t in such a hurry to hide the FBI and DOJ’s crimes and abuses. Perhaps most significantly, the Times avoided asking the key questions that the article raised with its revelation that “at least one government informant” met with Trump campaign figures.

So, how many “informants” targeted the Trump campaign? Were they being paid by the U.S. government? What are their names? What were they doing?

Under whose authority were they spying on a political campaign? Did FBI and DOJ leadership sign off? Did FBI director James Comey and Attorney General Loretta Lynch know about it? What about other senior Obama administration officials? CIA Director John Brennan? Did President Obama know the FBI was spying on a presidential campaign? Did Hillary Clinton know? What about Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta?

These questions are sure to be asked. What we know already is that the Times reporters did not ask them, because they do not bother to indicate that the officials interviewed for the story had declined to answer. That they did not ask these questions is evidence the Times is no longer a newspaper that sees its job as reporting the truth or holding high government officials responsible for their crimes.