The passing of Playboy creator Hugh Hefner at the impressive age of 91 marks the end of a life that had an enormous impact on media, culture, and sex. Hefner will be for the most part hailed this week as having a legacy of progressive advancement of sexual mores, with nostalgic references to the culture of free love and plaudits as a champion in the libertine battle against prudish Bible thumpers. But in fact, Hefner’s legacy is much more complicated than that, and much of Playboy’s struggles in recent years have more to do with the persistence of an underlying conservatism and traditionalism in view of sex roles and the nature of manhood. The inheritors of his magazine have attempted in awkward fashion to shove the now-problematic aspects of Hefner’s worldview out of view – including, in a most obvious fashion, the very thing he was known for in the first place. But it turned out that yes, the magazine still needed pictures of naked ladies to sell.

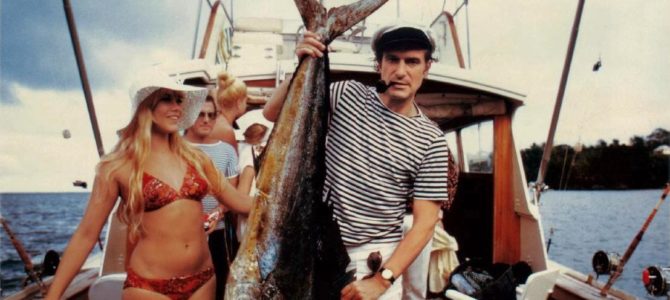

Hefner’s bet in 1953 was an salacious one at the time, but now it seems practically quaint. Hefner saw art in the naked female form. He saw the value in a purposeful life, but preferred it be more hedonistic. He liked fine tobacco and strong cocktails and stylish dress and fast cars, all while permanently surrounded by a habitat of gorgeous and willing women. Hefner was creating a brand out of thin air, and his publication was a presentation. It was a thumb in the eye of contemporary mores. But it was also a promise of a lifetime of escapist responsibility-free fun, and that if you followed his advice about being an American James Bond without the gadgets, you too could get that girl.

Along the way, he built a magazine that became known for excellent interviews and feature pieces written by some of the best writers alive. Among them was William F. Buckley, who wrote frequently for Playboy on all manner of topics. The magazine featured his 9,000 word debate with Norman Mailer, an 8,500 word essay on Richard Nixon in China, and writings on everything from communism to Y2K. James Rosen has a lengthy piece on the relationship between WFB and Hefner here.

Why did Bill Buckley, if he found the Playboy Philosophy so abhorrent, write for Hugh Hefner’s magazine so often and for so long? This question Buckley answered by noting that “the best writers in the world publish in Playboy”; but this alone did not explain the heresy, for the same was true, he acknowledged, of the Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s (for which he also wrote, though far less frequently). There were also Playboy’s five million readers and, best of all, Buckley quipped, it was “the fastest way to communicate with my seventeen-year-old son.

(Buckley managed to conclude his 1970 interview with the magazine with the line “I know that my Redeemer liveth”, and he took obvious joy in subverting their aims in their own pages.)

Hefner embodied a culture of libertinism and excessive excess, providing his readers a larger-than-life example of what one could do, if not necessarily what one should do. He also showed how the American entrepreneurial idea can be applied: with a thought and a little gumption, one can build an empire, and even if the magazine sales have dipped and fewer people read it for the articles, that sparkly little bunny with a bow tie slapped on all manner of product is as profitable as ever.

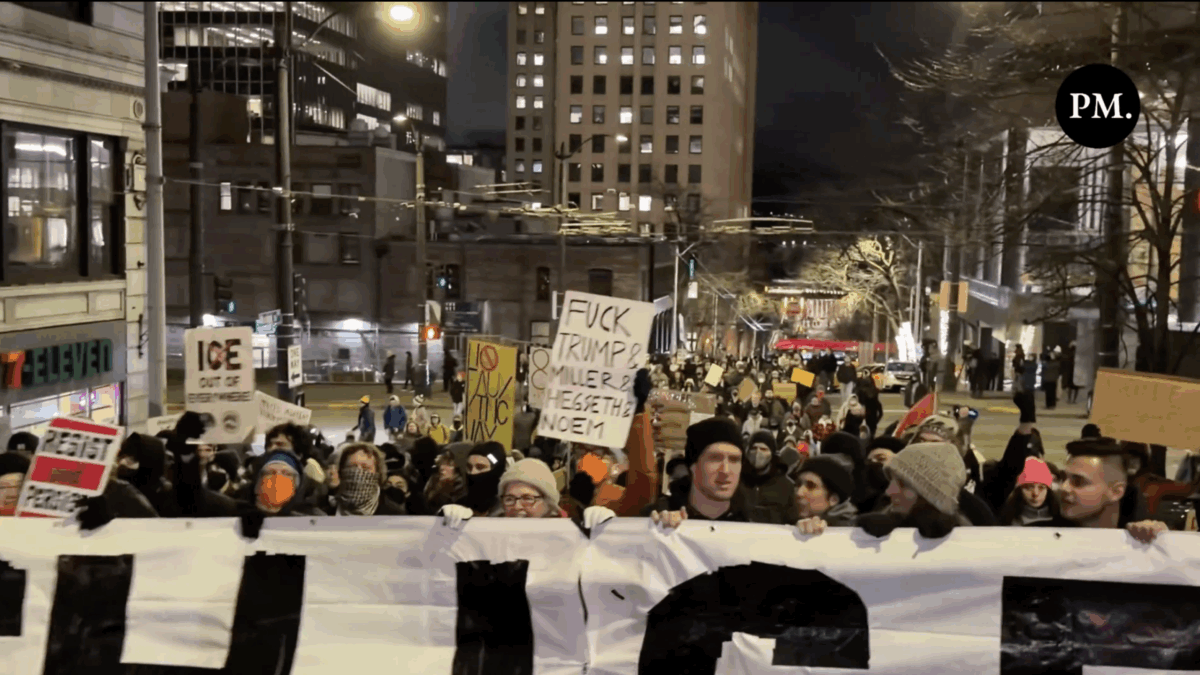

It is striking to consider the problems within Hefner’s throwback approach to sex and sexual relations, his obvious tensions in relations with the changing attitudes of modern feminism, and an enduring preference for free speech in all things. Hefner’s creation now seems less like a courageous progressive middle finger to the modern establishment, and more like the wishful thinking of an adolescent in grown-ups clothing. The vulgar side of what he did at the time seems positively quaint compared to the images and offerings that surround us today. You will find more explicit pornographic scenes in an hour of watching original HBO programming than you can find in a decade of Playboys, and images of women as scantily clad as his original purchased shots of Norma Jean are on the covers of magazines next to the Altoids in the supermarket. The confusion about where prudishness remains appropriate extends to CNN, which apologized to viewers recently for a guest’s use of “the B-double-O-B-S word”, but will go right along in highlighting the reaction to Hefner’s death from women he made famous for showing theirs off.

The Playboy Philosophy was inherently a part of the sexual revolution, yes, and Buckley was right to critique it. But it is apparent in retrospect that Hefner was not, as he perceived it, the captain of that revolution. What separates him from the more lurid members of his industry is an appreciation for manners and a particular form of American masculinity: he advised you to be a gentleman, not a cad, in your pursuit of the centerfold or the girl next door. As Lileks put it on Twitter yesterday, “Few men wanted to be Hef. They wanted to be the guy Hef was happy showed up at his party.”

Hefner’s death comes at a time of deep confusion for the country about all sorts of things sexual in nature. Embedded in his work was the idea that what we appreciate in one another isn’t sexless. It’s deeply rooted in our differences. Without those differences, sex itself becomes much less interesting. So while he was derided as selling prurience and stereotypes to the profane and stereotypical, he was actually celebrating the sexual complementarity that has bound men and women together since the dawn of time. The fact this idea has become a problematic one in some pockets of American culture is one Hefner would doubtless find absurd – he built an entire empire on it, after all.

Should you instruct your sons to follow his example, or your daughters to follow the example of those in his orbit? No, obviously not. But his joie de vivre, his appreciation of the beautiful, the finer things life has to offer? As Walker Percy wrote in Love in the Ruins: “What does a man live for but to have a girl, use his mind, practice his trade, drink a drink, read a book, and watch the martins wing it for the Amazon and the three-fingered sassafras turn red in October? Art Immelmann is right. Man is not made for suffering, night sweats, and morning terrors.” RIP.