On one of William F. Buckley Jr.’s “Firing Line” shows, Clare Boothe Luce intoned that “politics is the art of the possible.” The sarcasm in Buckley’s reply is unmistakable, though restrained, so taken aback must he have been hearing this cliché from a woman who took credit for FDR’s phrase “A New Deal” and Churchill’s “blood, sweat, and tears.”

It went something like: “Oh really, Clare. That’s so interesting.” But Clare was not one for flinching. She might even have taken credit for that line—except that Bismarck’s use of it, in 1867, would have revealed her to be rather older than she wanted to seem.

But is politics the art of the possible—the art of only the possible? Jim DeMint, the president of The Heritage Foundation, has suggested that the phrase traps us in the amber of yesteryear, where conservatives have been stuck for decades.

We’ve Made Our Peace With New Deal Politics

In Buckley’s 1955 mission statement for National Review, he described conservatives as, essentially, people “who have not made their peace with the New Deal.” But people calling themselves conservatives—by the score, by the hundreds, by the thousands—long ago made peace with the New Deal. They accepted not only the programs, but the premise of FDR’s game-changing political and social policies: Government knows best; therefore government will direct the economy and redistribute wealth in a more equitable fashion than the market or civil society can or will.

The New Deal was expanded by Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. We now have 80 programs costing more than $700 billion a year fighting poverty. Reagan was right: We waged war on poverty and poverty won. There has been no net decrease in poverty since the 60s.

Then came Nixon, and then went Nixon, but leaving us, before leaving himself, a slew of New-Deal-Great-Society-type programs: the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the 1972 Noise Control Act, the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, the 1973 Endangered Species Act, the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act, and probably more regulations than had been imposed on the economy since the New Deal.

Our Regulatory Age Is Out of Control

Remarkably, after all that, the liberal-progressives did him in anyway (he’d nailed Alger Hiss), prompting the late, great M. Stanton Evans to remark that he was never for Nixon, until Watergate. Evans said that when you looked at wage and price controls, OSHA, EPA, détente and Kissinger, going to China, and all the other stuff Nixon was doing, Watergate was like a breath of fresh air.

But the smog returned, and we had the Bushes. And then Obama, and his more than 20,000 regulations. The National Association of Manufacturers estimates that regulations today cost $18,000 per job.

So it’s easy to understand why many conservatives abandoned any plan of making no peace with the New Deal: Politics is the art of the possible.

Until it isn’t. Which looks like now.

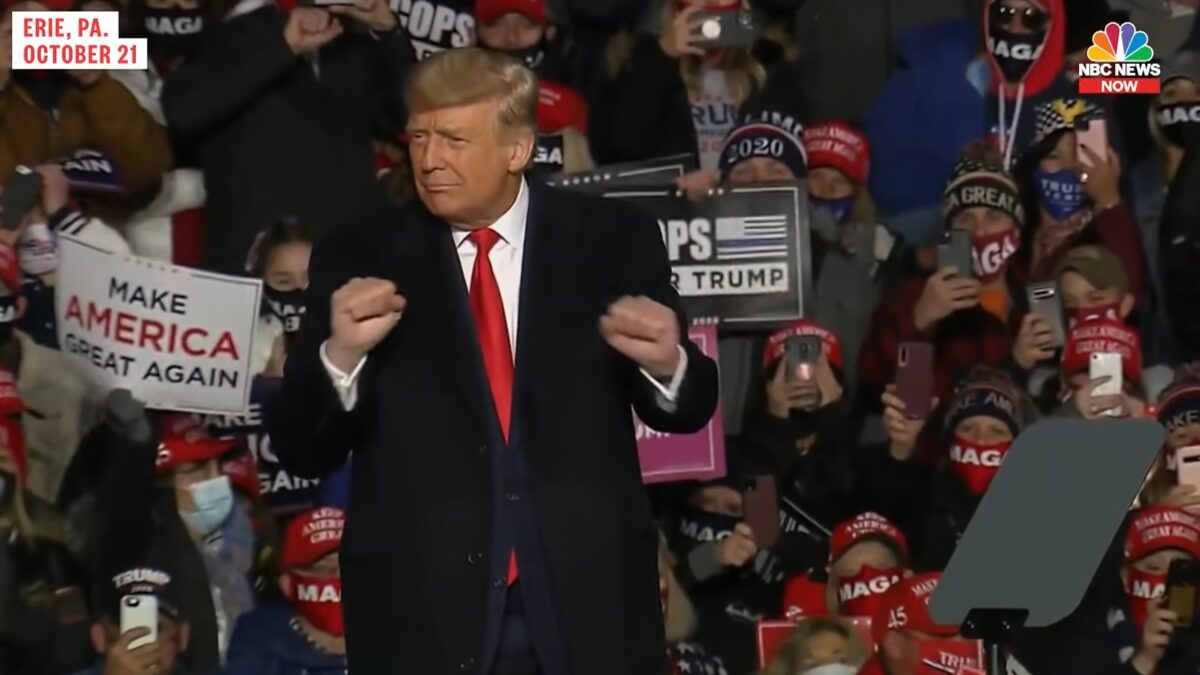

Could Trump Usher In A New Era?

The Republicans have won all three houses, which is more than Ronald Reagan did in 1980. This gives Trump a better chance to enact his programs than Reagan had. Maybe he can make America great again—a phrase no doubt whispered to him in his baby carriage by Clare Luce.

Trump has said he plans to appoint as federal judges people who will uphold and defend the Constitution; repeal Obamacare; secure the border; fix the tax code; promote school choice; make war on the regulatory state; defund Planned Parenthood; eliminate Dodd-Frank and perhaps Sarbanes-Oxley too; and on and on and on. The more he does at once, the easier it will be: Newspapers have only one front page.

At a recent gathering of conservatives and people close to the Trump transition team, the talk was of reducing the corporate tax rate to 15 percent and lowering the personal income tax—and perhaps stuffing a far-smaller IRS into a room at the Department of the Treasury. One said the Trump administration would promote the building of pipelines to make the country’s supply of natural gas more available—it’s the ultimate infrastructure project and isn’t financed by government. They estimate that each of those policies would increase GDP by 1 percent. GDP has been flat for the seven long years of the Obama Recession.

One panelist suggested eliminating the payroll tax, which only Al Gore (inventor of the Internet and man who once said E Pluribus Unum means Out of One, Many) thinks goes into a lockbox where it waits, safe from political hands, to be returned to the workers who paid it.

Trump Isn’t A Conservative, But He Is A Maverick

The policy people spoke of Trump’s endorsement of the “penny plan”, under which Congress would reduce discretionary spending by 1 percent each year (excluding defense, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid).

There was even talk of returning to the gold standard, one panelist saying that you can’t have free trade with floating currencies—a position Donald Trump seems instinctively to have understood, if not articulate. He focused on NAFTA, but the real problem, the panelist said, is that the peso went from being worth 33 cents in 1994 to 5 cents in 2016.

Will Trump do it all? Probably not. Trump is not a conservative, after all. He’s a maverick. But the lefty, progressive great-grandchildren of the New Deal fear he’ll do it all. They know now, if they didn’t before, that Trump has a backbone like the Washington Monument, an army of free marketeers and socially conservative policy people that could fill the Washington Mall, and a magaphone that lets him ignore the media.

Soon, sooner than they think—or conservatives ever dreamed—the art of navigating within national policies that allow freedom, opportunity, prosperity, and civil society to flourish may be the only politics that’s possible.