It has become nearly impossible to live in America without struggling against the inescapable dread that life has become overwhelmingly dull. The pervasive boredom of American life is largely a product of the predominant character of many American citizens – cowardice. The cowardly impulse manifests in many Americans finding perverse enjoyment in invented roles of victimhood, political correctness, and materialistic excess substituting for character and authenticity.

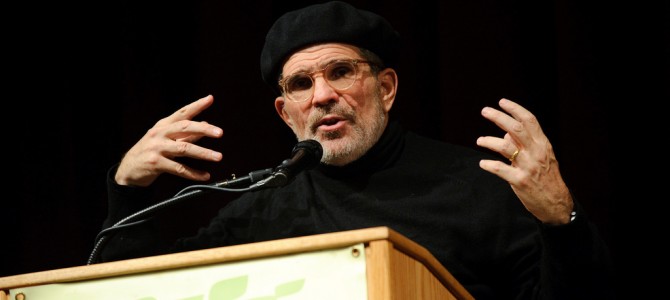

David Mamet, a Pulitzer Prize winning genius and giant of theater, film, and literature, has led a life of achievement in which he has made an immeasurable contribution to boredom relief in America. Recently, he has also generated his share of controversy by coming out as a conservative after many years of self-avowed “brain dead” liberalism.

The conversion announcement surprised many admirers of the Renaissance man, but some observers saw it coming for a long time, including political analyst and social commentator Shelby Steele, who said, “I think he (Mamet) has the same values today as he did before. He’s always been conservative without knowing it.”

When I had the pleasure of speaking to David Mamet on the phone recently, the perception that a gulf of dislocation separates Mamet’s early period of plays and film – Glengarry Glen Ross, American Buffalo, and The Verdict to name an illustrious few – from his current role as the rightward drifter in Hollywood, arose quickly.

“The left indicts anything that it cannot immediately identify as leftist as political,” Mamet said and insisted that his early plays for the stage and screen, including the aforementioned trio critics called “anti-capitalist”, were “apolitical.”

The ballistic combat of his characters, whether they are real estate salesmen in Glengarry Glen Ross, petty hustlers in American Buffalo, or a whiskey soaked, broke down lawyer wandering through fields of perdition in The Verdict, comes out of the necessity of drama – an imperative that relates and connects directly with Mamet’s method of viewing, receiving, and in his own way, with words of steel, ideas of electrical surge, and as he is the first to admit, feet of clay, wrestling the world.

Mamet’s plays, more than depicting a particular political way of understanding the world, show people’s natural tendency toward the adversarial, but as the great writer, who also spent years teaching at the college level, explains it, “Of course, we’re combative with each other, but we’re also combative within ourselves.”

“Everyone says I want to get to heaven in one form or another. Liberals seem to believe it is here on Earth if only the conservatives go away. Conservatives might think it is the striving for mystical perfection, which is never attainable,” Mamet said and then elaborated, “That’s the way it is from the start. That’s the Bible. God says, ‘Here you go. Just don’t hide in the closet.’ So, of course, many of us can’t help but go into the closet, but man is a striving animal. That’s what separates us from the poodles. So, our unquenchable urge to investigate, reform, and reshape everything around us, not only makes the world, but destroys the world. The question is how do we deal with human nature, and that is the ultimate question of drama.”

Drama 101 easily dovetails into Philosophy 102, and Mamet is so well read that he can seamlessly transition from one topic to the next. When I caught him on the telephone, he apologized for missing my first call. He was “sorting out boxes of old books” and he didn’t hear the ring, because he’s “deaf.” Creeping signs of mortality and the damages done to the body by that most hideous and universal process called “aging” is one of the many tragedies that human beings must suffer and endure, just as all people will eventually find themselves in one theater of war or another.

The “tragic view” is the connective tissue between Mamet, the self-proclaimed “inaccessible” loner who is a sharp and artistic observer of human affairs, and Mamet, the political provocateur.

“The combative nature of human beings in relationships with each other and in the understanding of themselves is the essence of the tragic view,” Mamet said before continuing, “The marvelous thing about my discovery of conservative philosophy and economics is that it made sense with my previous experience in the world. It is saying that there are things beyond our understanding, but by observing them we might be able to deal with them. We can never completely do away with the final remainder of discomfort, mutual loathing, and self-doubt, because that is part of the human condition. Whatever we do, the price of failure will be chaos, but the price of success will also be chaos.”

Victimhood

At 65, Mamet seems most concerned and fixated with the price of success for the “most productive country in the history of the world” – the schizophrenic, funny feast of contradictions that is the United States of America.

“After 230 years of incredible success, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that, for example, we have congressmen who are all thieves,” Mamet said, punctuated by a sardonic laugh fit for one of his most erudite characters.

Mamet has a rhythmic way of speaking that I found when replaying the recording of our conversation, is infectious, as I had started speaking in the Mamet melody too. The inventor of what critics call “Mametspeak” – a punchy, aggressive form of dialogue spoken by characters who continually interrupt each other – can be “spoken slowly”, the playwright insists, but must be read “rhythmically.” Like a wide keyhole on the door of an art museum, it also provides an insightful peek at the big picture.

Mamet’s characters rhetorically grapple with philosophical choreography to match the physical staging of professional wrestling, because they are pushing for position in a meritocracy where everyone must prove themselves. In Glengarry Glen Ross, the test of self-sufficiency and victory among real estate salesmen is known as “being on a sit,” and the characters clearly ration respect based upon who has and who has not been on a sit.

The Edge, a film about two enemies trapped in the wilderness struggling to survive, and Ronin, an intelligent action movie that likens rogue American spies in Europe to Japanese samurais, are two important chapters in Mamet’s continuing chronicle of masculinity, adversity, and in terms one of Mamet’s most obvious influences – Ernest Hemingway – would appreciate, life as an evolving test of testicular fortitude.

“I remember as a young man looking at my father, a successful businessman, and thinking, ‘I don’t know anything. How am I going to matriculate into society and become self-reliant?’” Mamet said. “A healthy society helps a young man or woman matriculate. It says, ‘Off you go into something in which you’ll be judged.’ Then, the fear of matriculation is gradually replaced by the physical memory of accomplishment. So, little by little, it gets easier.”

It is the well-intentioned, but destructive attempt to assuage the fear of matriculation, and the lack of incentive to prove one’s worth, competence, and skill, that have created a culture of conformity, weakness, and banality. “If one tries to save the young from the rigors and traumas of life, you’re saving them from life,” Mamet said.

The degradation of the modern university experience – a topic he explored with Oleanna, a play that savagely disembowels the absurdity of political correctness in higher education – is one example Mamet identifies to illustrate the escape plan from life that many young Americans, often with the assistance of their parents, execute: “What is college? Nothing. Students learn five recognition symbols that make them comfortable in conversation with other people who know nothing. And they don’t realize that they’ve learned to rely too much on others.”

The idea of “recognition symbols” is important to Mamet, as he returned to it several times during our conversation. Recognition symbols are the slang terms, jokes, and archetypes that minority groups employ to signal their understanding of and belonging with each other. Mamet began with the example of his Jewish ancestors vacationing at the Catskills and other resorts, and entertaining themselves by telling jokes about certain Jewish stereotypes of the “passive” or “overly neurotic” man. “These were just jokes,” Mamet insists, and then explains that problems of personal demoralization and social division materialize when people begin to take the jokes seriously, internalize the recognition symbols as foundational of identity, and “self-adopt” stereotypes.

“I was a straight guy in a gay business,” Mamet said referring to his early days working in Chicago theatre, “and my gay coworkers had their recognition symbols too, but I was always impressed by their generosity and matter of factness about my otherness.”

“They just accepted me into the meritocracy,” Mamet said, and once again returned to his holy trinity of the healthy life and society – competition, proving one’s own self-worth, and matriculation by way of earned achievement.

Mamet worries, much like Gore Vidal did before him, that too much of the gay rights movement, similar to many Leftist Jews, have embraced the stereotype of the victim, rather than recognizing themselves as “tough as nails.”

The anger in Mamet’s voice ratchets up a few levels when he applies the same theory to African-Americans. For a man whose plays are notoriously profane in their language, he is surprisingly reserved with expletives. Jack Lemmon, one of the stars of the film adaptation of Glengarry Glen Ross, joked that he should change the name to “Death of a F***in’ Salesman,” and when I ask about the liberal tendency to relegate black Americans to roles of noble victimhood, he answers back, “It’s f***ing dreadful.”

One of Mamet’s recent plays, Race, is about a controversial trial full of racial implications. He wrote it to tackle America’s “hypocrisy” on the most intractable of social issues.

“In the African American community, one of the legacies of slavery that Thomas Sowell writes so beautifully about is that the generations that endured slavery were the toughest people in the world,” Mamet explains. “The legacy is not that they emerged as slaves, but that they transcended it, and didn’t want to go back. Then Lyndon Johnson comes along and says, ‘I can help you.’ Well, he helped them right back, but that’s human nature.”

The great jazz critic and essayist Stanley Crouch makes the compelling point that the invention of modern music, and the establishment of the blues aesthetic, by illiterate slaves in cotton fields might very well be the “greatest achievement in the history of the species,” but all America hears and sees every February, during black history month, are the slave narratives and pictures of fire hoses.

Mamet pointed out that one of the most tired, and tiresome, tropes of American politics is the piety that “we must have a dialogue on race.” “We’ve been having one continuous dialogue on race for my entire lifetime, and it only worsens and widens the divide,” he said before explaining that American liberalism infantilizes black Americans in a culture of dependency. “Black people”, Mamet pointed out, “are sufficiently smart and strong not to need the paternalism of good willed white liberals to make it.”

Cowardice

In Mamet’s new book, an insightful and entertaining collection of novellas called Three War Stories, one of the stories is about a soldier’s conflicted feeling regarding the Plains Indians of the Nineteenth Century. He has heard the State’s dogma depicting the tribes as savages and sloth, but what he has witnessed tells a different story.

Mamet believes that it is liberal political correctness that erases the indigenous story from American history. “Totalitarian thinking”, his nickname for political correctness, “reduces them, along with black Americans, to one fact – they were victims.”

His study of the Native Americans, which began with an article for the Smithsonian National Museum on Buffalos and the “national shame” of American atrocities toward Natives, led him to the discovery that “One sees how a primitive society has all the elements of ours, which is just another primitive society with a lot more technology.”

Less drive, aggression, and energy lead to less excitement, fun, and variety. If there is one element of life that should forever live with immunity to boredom it is sexuality, yet America has managed, against all the odds, to make sex boring. Pop culture’s predictable vulgarity, along with young Americans’ rejection of romance and fear of intimacy, leads to laughable events like “Sex Week”, a sexually instructive and controversial event that takes place annually at college campuses across the country.

When I brought up Mamet’s shocking, absorbing, and sexually explicit play Edmond, which Stuart Gordon turned into a film starring William H. Macy in 2005, the playwright returned to a statement he makes on the commentary track of the Edmond DVD: “American men are terrified of sex,” and quickly transitioned into Sex Week – “My understanding of Sex Week is that it is an attempt to get otherwise disinterested students to attend lectures on techniques and sales demonstrations of devices.” After I assured him that he is correct, he asked, “What’s happened when a 19-year-old American male is jaded about sex?”

“Part of the matriculation process for a young man has always been”, Mamet continued, “I don’t know how to make a living, but I better figure it out or I’m never going to get laid. When you take that away, you take away the strongest goad he will ever experience in his life.”

In her book, The End of Sex, Donna Frietas reports her findings after a thorough investigation of “hook up culture.” Many American college students never date and rarely flirt, but satisfy their hormonal cravings by anonymously pairing off at the end of a night of binge drinking for anonymous, fumbling, and sloppy sex. Frietas interviewed thousands of students, and found that most of them are dissatisfied, bored, and unhappy with their sex lives, but due to peer pressure, lack of imagination, and a deficit of courage, have no exit strategy from the tedium and mechanical degradation of sex that they label with a phrase probably more fitting for instructions that come with a television set.

“Of course they’re bored. Why wouldn’t they be?” Mamet asked when I informed him of Frietas’ findings, “We’ve become like the sultans with 500 concubines. They don’t want to have sex either, and why should they?”

In Mamet’s Academy Award winning film, The Verdict, Paul Newman gives one of his finest performances as a hard luck lawyer who, after years of decadence and depression, finds a reason to fight for what is right and redeem himself after years of spiritual poverty. Mamet told me that “Newman’s character was trying, as many Americans are now, to deny the life of the soul.”

“It is hard to come back to life,” Mamet said, “Especially when your country is doing what all great civilizations have done, which is to try to use its wealth to eradicate human nature.”

The connection between the perdition in The Verdict and the lack of vitality in America set Mamet off on a delightful tear – “I just read that in Los Angeles, a restaurant with 40 kinds of water has a water sommelier. I thought it was a great gag at first, but it wasn’t. We need someone to talk us through f***ing waters. There’s something greater than ourselves that might cause us to wonder why we are here and how we should deal with each other. If we deny the urge to meaning, we deny it at the cost of our soul. And then we have to keep increasing the dosage of that which is poisoning us.”

If sex has become the product of a bipolar adolescent – at once terrified and thoughtlessly ravenous – marriages have also begun to fail. Mamet, also while reflecting on Edmond, once said that “most American marriages are unhappy.” He’s been married to actress Rebecca Pidgeon for 22 years, all of which Mamet boasts have been “nothing but chuckles.” “Maybe marriages are made in heaven,” he wondered.

Most marriages wind up in hell, however, because they are no longer “part of matriculation”, and therefore, people go into them with absurd expectations that Mamet calls “bad greeting card poetry,” such as “let’s enhance each other in our thoughts,” and “give each other space.” His rabbi tells him that marriages depend on a commitment to “not share each other’s feelings.” Mamet adds that they also depend on clearly defined goals – “to love, honor and protect.”

It is the difference between “telling a young boy to go to the grocery store for milk,” Mamet explains, “and telling him to go out and get something.”

“If you’re living in a world where feelings are all that matter, you’ve never left the womb,” Mamet concluded.

Joy

Mamet, a wildly successful man, worries that too much success is corrosive to the soul of America, and while a Hollywood legend might not make for the most obvious spokesman of the spiritual jeremiad, he does make for an undeniably interesting and powerful one. He is at his strongest when he describes the decline of the neighborhood throughout America.

“Los Angeles is, as a company town, a shithole. It is full of mendacious swine like me,” Mamet said, “But it is filled with these mini-malls, and no one knows what is in there. It is exciting. It is like when I grew up on the Southside of Chicago. There would be a candy maker next to a skate sharpener. Wabash Avenue in Chicago was the most exciting street in the world. The El train was overhead. It was the last vestiges of merchants of the frontier. There was the emporium of people selling guitars and guns, and the great clothing stores. And that is due to the immigrant groups who would come to a new place and think, ‘What is needed here and what can I do?’”

Mamet’s tone of voice dropped down when he seemed to measure the cultural famine that lack of hunger creates in American culture, “But you walk down Madison Avenue in New York and its Movado watches, and the next store sells Rolex watches.”

In Mamet’s 1997 collection of essays, Make Believe Town, he paid tribute to one of the most essential and beneficial institutions of American life – the diner. He opines beautifully that, “Those who have not experienced the glow engendered on one’s entering the coffeeshop and having the server inquire, ‘The usual?’ are poor indeed.”

There are many impoverished Americans, as the communal experience of the diner continues to vanish, leaving open socially infertile ground for the growth of imposter chain restaurants and bars without ambiance.

Mamet submits that “it is a natural outgrowth of success that communities have become polarized by politics. One doesn’t have to talk to people of differing views,” and he hastens to add that “Fifty years ago, Eric Hoffer said we are destroying the middle class, and with it the humor and wit and essence of America. The left doesn’t understand that often the guy or the woman who starts the small business might be making less money than the people they employ. They just like running their own lives.”

The man who cherishes the entrepreneurial spirit, treasures competition, and strives to advocate the self-reliant drive that makes life interesting, electric, and rewarding, admits that, many years ago, he was a misfit. He hovered on the outer edge of his culture, unsure how to make a living, matriculate into meritocracy, and capitalize on middle class opportunity.

“Some people have the joy of competition more than others. Societies have always made room for those who don’t. I’ve been very fortunate to fill that operation in my culture for a long time. I didn’t know how to do anything. I was confused. I was unemployable. But guess what? I discovered a talent, and the culture said that if I worked hard at it, there might be a place for me.”

After a pregnant pause, and slight sigh of relief, he added, “Kind of marvelous.”

Even more so for those who continue to find joy and wisdom in his beautifully pantheonic and statuesque body of work.

David Masciotra is a columnist with the Indianapolis Star. He has also written for the Daily Beast, the Atlantic, and Splice Today. He is the author of All That We Learned About Living: The Art and Legacy of John Mellencamp (forthcoming, University Press of Kentucky).