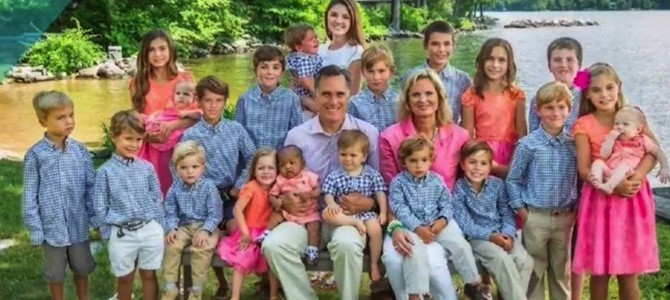

Americans are talking a lot about race nowadays. It’s an interesting feature of race-related stories that the commentariat is perpetually scrambling to explain what the story really is. Not every story is like this; for example, when Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines last year, no one had trouble understanding why this was newsworthy. By contrast, the dust-up over Mitt and Ann Romney’s Christmas photo (which featured all of their grandkids, including an adopted African-American child) was something of a puzzler. Why exactly do we need to talk about that?

One is tempted to laugh such things off as “slow news cycle” fare, but that can’t be the whole explanation because some of these stories do explode into major conflagrations. The most obvious recent example revolves around the death of Trayvon Martin and the subsequent trial of George Zimmerman. These surely ranked among the most significant national news stories of 2012 and 2013. Nevertheless, the coverage played out as a particularly grotesque game of “find the story.” Obviously, the untimely death of a young person is sad. But unlike, say, Kermit Gosnell’s chamber of horrors, the death of Trayvon Martin really should have been classified as “local crime.” (Whether Martin or Zimmerman was guilty of criminal behavior I do not know, but clearly at least one behaved improperly.) Nothing about the Zimmerman incident in and of itself that merited even a fraction of the media attention it received.

Consequently, we were treated to a plethora of essays diagnosing the true meaning of the whole dismal saga. Perhaps the case was an indication of how, even today, racism lives, and justice eludes the black man. Or perhaps it was a lesson in the need for greater gun control. Then again, it could be a story about liberal exploitation of racial issues for political gain. Or about the way community protection has been so institutionalized as to prevent ordinary citizens from keeping their neighborhoods safe.

The story had legs longer than a giraffe’s, so I suppose it could sustain quite a number of morals on its broad back. To me, however, the important lesson was twofold. First, Americans still have not found a healthy way of approaching racial issues. And second, Barack Obama’s presidency has considerably worsened race relations in this country. Compared to the Zimmerman incident, little dust-ups about “black Santa” or the Romney Christmas photo are just ripples on the pond, but even these are evidence that the fires of racial angst are still smoldering, and it’s only a matter of time before another relatively minor incident sparks another massive conflagration.

The Special Dilemma

Perhaps it would help to take a few steps back and ask: why are racial issues so hard? Although it’s obvious that racial angst is frequently exploited for political gain, it isn’t purely manufactured. Narratives can’t be spun out of nothing; somewhere there must be a wellspring of feeling that politicians and journalists can tap.

The left is wrong, however, to suggest that the primary source of racial tension is hatred, or the proverbial “fear of the other.” Actually there isn’t much racial hatred left in America today, and the overwhelming majority of us recognize racism as a bad thing that we emphatically wish to avoid. It’s interesting that the most explosive race-related story of the past few years sprang from an incident that was never persuasively shown to have anything to do with race. It’s also interesting that the riots that so many predicted following the Zimmerman verdict never really occurred. There doesn’t seem to be much appetite in America for battering or banishing one another over issues of race.

Griping, stewing, seething and hand-wringing remain quite popular, however. Clearly, passive-aggressive racial tension is preferable to overt violence, but it also points towards a more complicated set of problems than simple, old-fashioned bigotry. It points not to the sorts of problems that arise when people want nothing to do with one another but, rather, to the sort that arise when people do want to live together but aren’t sure how.

Racial questions drag us into the heart of an ambiguity that recurs regularly in the lives of individuals as well as groups. In basic terms, we must constantly ask ourselves: Do I want to be special? Or would I rather be one of the gang? There are obvious tensions between these two alternatives, but the problem is that we want both. In fact, we need both. As social animals, we need to carve out a place in civil society, but we also need for our unique personality and talents to be affirmed. Meeting both needs is a real challenge, and as we grow up we have to learn when it’s appropriate to assert ourselves, and when we should fall into line. Some people never really find the right balance.

The Special Dilemma arises with respect to groups too, including ethnic groups. Do I want my ethnic heritage to be dismissed as mostly irrelevant, so that I can be treated exactly like everyone else? Or do I want the distinctive features of my group to be noticed and celebrated? As in the individual case, we want both, and it can be genuinely tricky to find the appropriate balance.

The Argument for Colorblindness

Conservatives have a particular distaste for special pleading, so they often try to resolve the dilemma by opting aggressively for “non-special”. They call for a “colorblind” society in which people simply don’t notice one another’s race. This is a more rational way to live (or so the argument goes) because a person’s ethnic background really says almost nothing about him. Most of our ideas about race spring from a backwards pseudoscience that has been completely discredited. Enlightened modern people should realize that there really is no reason to care greatly about race.

There are a couple of problems with this argument. First is the fact that most of us inherit more from our ancestors than just genes. We inherit a culture, along with specific customs that influence our worldview and our sense of identity. These associations are circumstantial, of course, but that doesn’t make them either unreal or unimportant. We cannot ask people to stop taking pride in their ethnic heritage, any more than we can decree that people should not be patriotic. Very few of us choose our nationality, but we can still be proud of it because our nation is far more than just a latitude and longitude; it comes with a history and cultural heritage that for most of us comprise some significant part of our identity. For many, race has a similar sort of significance.

The second thing to realize is that colorblindness really is not particularly rational, nor does it come naturally to us. As part of living in the world, we constantly take note of people’s superficial characteristics and use the information we glean to form snap judgments about them. Why rely on superficial characteristics? Because those are the ones we can see, and we don’t always have time to get to know a person intimately before deciding how to respond to him.

Now, admittedly, the relationship between ethnicity, culture and identity is complicated, and any conclusions we draw about a particular person based on his ethnicity should be highly tentative. Typically, ethnicity will be noted in combination with a panoply of other observable characteristics (age, sex, dress) that combine to create an impression of the person. It’s a fancy bit of inductive reasoning that cross-references various sets of data to yield a rough probabilistic assessment of the odds that a particular person is dangerous, or in need of assistance, or likely to be suckered into buying time share. Ethnicity won’t always be a large component of that calculation, but factoring it into the mix is not, in itself, either irrational or bigoted. It’s just something humans do as a way to cope with the reality of constantly needing to act on limited information.

Perhaps the best thing, then, is to abandon the ideal of colorblindness, and instead to think about racial issues as an application of the Special Dilemma. Racial tensions flare up in situations where we have trouble resolving that dilemma. The solution, then, is to consider carefully the extent to which each sort of claim (to non-special treatment or to special treatment) is legitimately pressed.

Racial Profiling

Racial profiling is a good case study. In making the (readily understandable) judgment that a young African-American male is a greater threat than a young white female, a security guard is doing his job in an entirely rational way. Security guards must regularly exercise inductive reasoning of the sort I explained above, so that they can decide where to direct their attention and time. Asking a guard to colorblind himself would be, in effect, asking him to do his job less well.

At the same time, though, it shouldn’t be so difficult to understand those sensitivities. In detaining the young African-American, even for just a minute or two, the guard is implicitly calling attention to certain weaknesses of African-American culture that its members (if indeed they see that culture as a significant component of their identity) presumably find painful. No one wants a group with which he identifies to be “appreciated” in such an obviously negative way. It is an indignity that goes far beyond the minimal inconvenience, especially since it serves as an unpleasant reminder that the general failings of a demographic group do end up reflecting back on those who visibly fall into it, at least in more casual encounters.

I suspect that a similar kind of shame can at least partly explain why some would be tempted to make wildly inappropriate jokes about Romney’s adopted grandson. In America today, quite a number of white families (usually religious) have volunteered to adopt black children. The reverse is much more rare. That says something about where functional families can be found, and where they can’t. It’s not remotely strange that this realization should make people uncomfortable, and it’s unsurprising that some would want to diffuse that discomfort through humor.

Thinking through the alternatives, I think most Americans will prefer to see racial sensitivities take a back seat in the above cases. Preventing violent crime, and providing orphans with loving families, are higher priorities than sparing ethnic minorities from painful reminders of the failings of their sub-cultures. Still, there is a value in appreciating that the offense people take in these practices is understandable and sometimes even reasonable. Insofar as we can take some pains to minimize the negative impact (for example by urging the security guard to be as courteous as possible), we should do that.

Affirmative Action

Another sort of race-related controversy springs from liberal efforts to “celebrate” particular ethnic groups by giving them special advantages, in the work force or in education. Conservatives often argue that these efforts are unneeded and unfair. Thinking about the problem in terms of the Special Dilemma may help us to articulate the objection better, while still appreciating the generous impulse that may underlie some of the support for affirmative action.

Affirmative action is often applied in situations in which we already have strong intuitions about how the relevant goods or opportunities should be distributed. In general, we feel that professional opportunities should be awarded to those whose credentials or demonstrated competence prove them worthy. Bypassing those obviously relevant considerations in order to celebrate a particular ethnic heritage seems inappropriate and perhaps unjust. It is a case in which the demand for “non-special” treatment (that is, the right to compete regardless of one’s ethnicity) seems eminently reasonable, but the demand for “special” treatment (that is, the opportunity to bypass a more qualified person in order to represent one’s ethnic group) does not.

As Charles Murray has repeatedly argued, awarding special benefits for inappropriate reasons can work to the detriment even of those we intended to help. Thus, ethnic minorities in America sometimes suffer from what Murray calls “reverse racism”. Even when they are eminently qualified for a position or opportunity, people patronizingly assume that they are merely the beneficiaries of special benefits. This in itself can become an obstacle that prevents qualified minorities from rising beyond a certain professional level. Having repeatedly been singled out as “special” on account of their ethnic background, they become ineligible for those benefits that can only be won from the ranks of the non-special.

Having reached a point where university admissions are routinely and significantly distorted by affirmative action, it seems clear that the effort has moved beyond cultural celebration and into cultural compensation. Liberals feel bad about the catastrophic social breakdown that disproportionately affects minority groups, but they don’t know how to fix the problem (or don’t want to), so they go on treating the symptoms with affirmative action. Far from fixing any of the real problems that ethnic minorities face, this leaves us all to live with the ill effects of treating a group as special when non-special treatment would clearly be more appropriate.

The Way Forward

America is currently in something of a racial funk. Think of us as being at that point after a major argument when you’re ready to make it up, but can’t quite figure out how to get started. Barack Obama’s presidency has put everyone in a particularly peevish mood, because it has shown us that neither side’s favored solution (for conservatives, colorblindness, and for liberals, stamping out rank bigotry) will help. We can’t be completely colorblind, and there isn’t much bigotry left to stamp out, so we’ll have to come up with something else.

The Special Dilemma might help us to find a new approach. Conservatives should let go of their grudges and cheerfully acknowledge that cultural appreciation can be a good thing. In the right context, we should be eager for opportunities to improve our understanding of the different idiosyncratic sub-cultures that make America the fascinating nation that it is. Also, we should show real concern when social breakdown within those sub-cultures darkens the prospects of particular ethnic groups. And it’s not too much to ask that we endeavor to approach sensitive topics sensitively.

Liberals, for their part, need to acknowledge that cultural celebration has its limits, and that it is no longer plausible to suggest that bigotry (whether overt or subtle) is the primary thing that prevents minority groups from thriving in America today. Just as individuals can be “spoiled” by too much special treatment, so too groups of people can be disadvantaged when they are inappropriately singled out. Moving forward will require us to find a healthier balance, so that we can enjoy the genuinely positive elements of cultural and ethnic diversity while also forging a nation in which everyone has an opportunity to thrive.

Rachel Lu teaches philosophy at the University of St. Thomas. Follow her on Twitter.