To some extent, the backlash that Jack Smith has been receiving since the unprecedented indictment of former President Donald Trump is unfair — he’s merely a symptom of a larger problem that predates his promotion in 2010 to helm the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Public Integrity Section and his more recent assignment as special counsel in the Trump documents case. But the backlash is also predictable, as Americans grow increasingly intolerant of what they perceive as two standards of justice.

To be clear, all prosecutions involve discretion — and with that comes the obvious peril of having that discretion influenced by bias. Any prosecutor or commentator that says bias doesn’t creep into all these decisions is lying to themselves and you.

This is likely where the cries of “but her emails” have some merit — the discretion exercised in the Hillary Clinton case of mishandling classified information was entirely different than in Trump’s current case. Of course, the fact patterns are different, so there is no common rubric that would allow a direct comparison, but you could easily write up a damning indictment of Clinton’s misuse and obstruction. Comey acknowledged the FBI avoided doing that because the election was looming and they didn’t want to trigger a constitutional crisis (because he erroneously assumed she would win).

Whether Comey’s decision to inject his invented standard of “no reasonable prosecutor” into the decision about Clinton’s case rises to an abuse of prosecutorial discretion remains debatable. Admittedly he wasn’t even a prosecutor, though he did assume that role by interposing himself between the investigation and the DOJ and effectively closed the case instead of referring it to DOJ. In the public perception of a wide swath of America, this unprecedented action by the FBI director was clearly an example of two standards of justice. Attorney General Merrick Garland’s decision to charge Trump only increases the “two standards” chorus.

Questionable Track Record

In an analysis of DOJ misconduct, one case casts a long shadow: the investigation, trial, and conviction of Republican Sen. Ted Stevens, with the ensuing scandal of misconduct and subsequent dismissal. Of course, his “exoneration” came only after irreparable damage to his reputation and the destruction of his political career had already occurred. That his defeat meant a Democrat would represent Alaska in the Senate for the first time since 1981 and go on to cast the deciding vote for Obamacare only adds to the sting of the injustice in the eyes of many Americans.

The entire prosecution team was replaced after a government whistleblower accused the team of misconduct and the case was eventually dropped at the behest of Attorney General Eric Holder. Amid the scandal, William Welch stepped down as Public Integrity section chief and moved back to Springfield, Massachusetts, before being invited back to Washington a month later by Lanny Breuer, then head of the DOJ’s Criminal Division.

Breuer, who had previously defended Sandy Berger for stealing an unknown number of classified presidential records from the National Archives, ironically put Welch in charge of investigating and stopping national security leaks. In that role, he was assigned the case of Thomas Drake, an National Security Agency employee who was charged under 18 USC 793(e), the Espionage Act. That case was ultimately pleaded to a misdemeanor amid excoriating criticism of the government’s conduct.

Investigation in the Wake of Misconduct

Five weeks after Stevens’ guilty verdict, a whistleblower came forward to allege misconduct on the part of the FBI and DOJ. Judge Sullivan scolded prosecutors for their conduct during the trial and found them in contempt, and in the aftermath ultimately appointed a special prosecutor amid concerns the DOJ was dragging its feet investigating itself. Henry Schuelke, a former federal prosecutor and defense attorney, with experience overseeing a Senate Ethics Committee investigation into former Republican New York Sen. Alfonse D’Amato, was tapped to spearhead the investigation.

For his part, Schuelke did a thorough job investigating the DOJ and the circumstances surrounding the case. After almost two and a half years and nearly a million dollars, he delivered a 500-plus page report. Described by Pace University School of Law Professor Bennett L. Gershman as “an extraordinary contribution to criminal procedure,” the report was damning:

No other official documentation or investigative study of a criminal prosecution, to my knowledge, has dissected and analyzed as carefully and thoroughly the sordid and clandestine actions of a team of prosecutors who zealously wanted to win a criminal conviction at all costs. In examining this Report, one gets the feeling that as the investigation and prosecution of Senator Stevens unfolded and the prosecution’s theory of guilt unraveled, the prosecutors became indifferent to the defendant’s guilt or innocence. They just wanted to convict him. Based on depositions of these prosecutors, their e-mails, notes, memos, conversations, court filings, transcripts of testimony, and oral arguments, the Schuelke Report methodically and exhaustively documents the way these prosecutors manipulated flimsy, ambiguous, and unfavorable evidence; systematically concealed exculpatory evidence from the defense and the jury; and thwarted defense attempts to locate that evidence in order to convict a United States Senator and destroy his career. (Emphasis added.)

Ultimately Schuelke wrote, “we do not believe that a criminal contempt prosecution under 18 U.S.C. §401(3) should be initiated against any of the subject government attorneys.” But this must be tempered with the narrowness of his role as a judge-appointed special counsel — being appointed by the judge, he could only investigate contempt, not other violations of law:

We conclude, however, that the record demonstrates that Judge Sullivan admonished the Government to ‘follow the law’ and did not issue a clear, specific and unequivocal order such that it would support a finding by a District Court, beyond a reasonable doubt, that 18 U.S.C. §401(3) had been violated.

In other words, the DOJ prosecutors escaped a finding of contempt by Schuelke, and thus any potential criminal sanctions by Judge Sullivan, on a technicality, since the judge never entered an explicit order to “follow the law.” Schuelke did however drop this subtle footnote into his final conclusion: “We offer no opinion as to whether a prosecution for Obstruction of Justice under 18 U.S.C. §1503 might lie against one or more of the subject attorneys and might meet the standard enunciated in 9-27.220 of the Principles of Federal Prosecution.”

In a 2012 interview for the Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit, Schuelke was less coy:

I had concluded that two of the prosecutors who happen to have been Assistant U.S. Attorneys from Alaska had engaged in intentional misconduct in the withholding of two discrete pieces of significant exculpatory evidence which in my judgment may well have proved to be the difference for the jury who heard the case. I concluded from the circumstantial evidence that I believe to be compelling, that their conduct in these instances was indeed willful and intentional. … Now, I persist in my view and I think the evidence compels the view that the conduct of these two prosecutors was willful. (Emphasis added.)

Regarding the report’s footnote about obstruction of justice, Schuelke confessed:

That footnote was in there, it was out, in was in, it was out, because I was … back and forth because I had an internal debate about, whether this gratuitous observation of mine was appropriate; because of course when I said I expressed no view about whether such a prosecution would lie, that probably suggested that in my view it would. … And, I ultimately decided to leave it in.

Worse Track Record In Probing Itself

Since Schuelke was powerless to pursue an obstruction of justice charge, it was left up to the DOJ’s Office of Professional Responsibility to mete out punishment for the conduct of the prosecutors on the case. Their findings resulted in recommendations for a paltry 40-day suspension for one prosecutor and a 15-day suspension for another.

Schuelke, in his interview, pulled no punches when it came to the Office of Professional Responsibility:

Now OPR, for the last 30 years, has enjoyed a terrible reputation among practitioners in the criminal defense arena. It’s the place in the popular view where allegations against prosecutors go to die, and my own experience and observations over these last 30 years are consistent with that view. … I and any number of my colleagues at the bar who have become familiar with this matter … have observed to me: “You know? If that were one of us on the defense side, we’d be in jail. That’s obstruction of justice. They wouldn’t hesitate for ten seconds to prosecute one of us.” I subscribe to that view as well. And so I personally found this outcome, while not surprising given the history and given the fact that you have an institution investigating its own, disturbing and somewhat surprising because it’s a political problem for the Department of Justice. (Emphasis added.)

Those scathing comments were made in reference to the modest administrative sanctions that the Office of Professional Responsibility recommended, and before the prosecutors successfully overturned their modest suspensions by appealing to the U.S. Merit System Protection Board (MSPB), which affirmed the “decision to reverse the suspensions based on harmful procedural error.” The MSPB awarded back pay and attorney fees to the prosecutors. The MSPB bills itself as “an independent, quasi-judicial agency in the Executive branch that serves as the guardian of Federal merit systems.” In practice, it serves as a congressionally sanctioned job protection racket for federal employees.

The Swamp Protects Its Own

Whether you’re a prosecutor in a public integrity case obstructing justice getting off scot-free, or a former FBI deputy director fired for “lack of candor” getting reinstated and paid $700,000 through a settlement with the subsequent administration (e.g. Andrew McCabe), or a convicted FBI Russiagate forger getting reinstated by the D.C. Bar, the message is clear: The system will take care of you. As long as you’re “on the right side of history,” one supposes.

While some have argued that the Stevens case was a “trial run” for framing Trump as a Russian asset leading up to the 2016 election, it’s unclear if it was really that insidious or just emblematic of an overall approach to “getting their guy” regardless of the facts — even more so it seems if the politician is Republican — that pervades the DOJ and FBI.

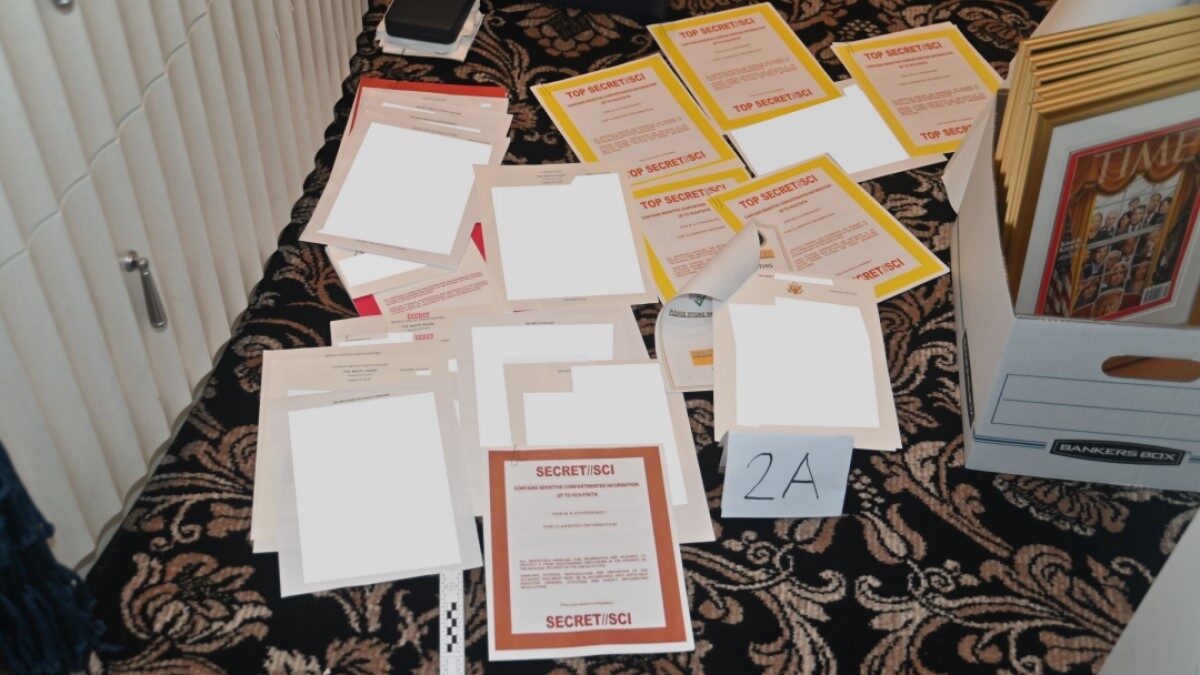

The department willingly finds its own employees merely “reckless” when destroying a senator by their misconduct and a certain former secretary of state “careless” when mismanaging classified information in a way that put it at risk of intercept by foreign hackers. Yet it insists Trump was “willful” in his alleged unauthorized retention of national defense information. This only plays into the perception of a two-tiered justice system.

One thing is for certain: There is little public evidence to suggest the Department of Justice has done anything to moderate its historical tendency to approach politically charged cases with an “ends justifies the means” approach. History will decide if Smith’s unprecedented indictment of Trump is another example of an overzealous prosecutor weaponizing the justice system, but Stevens’ words ring true for the former president now as they did for the former senator then: “Their conduct had consequences for me that they will never realize and can never be reversed.”