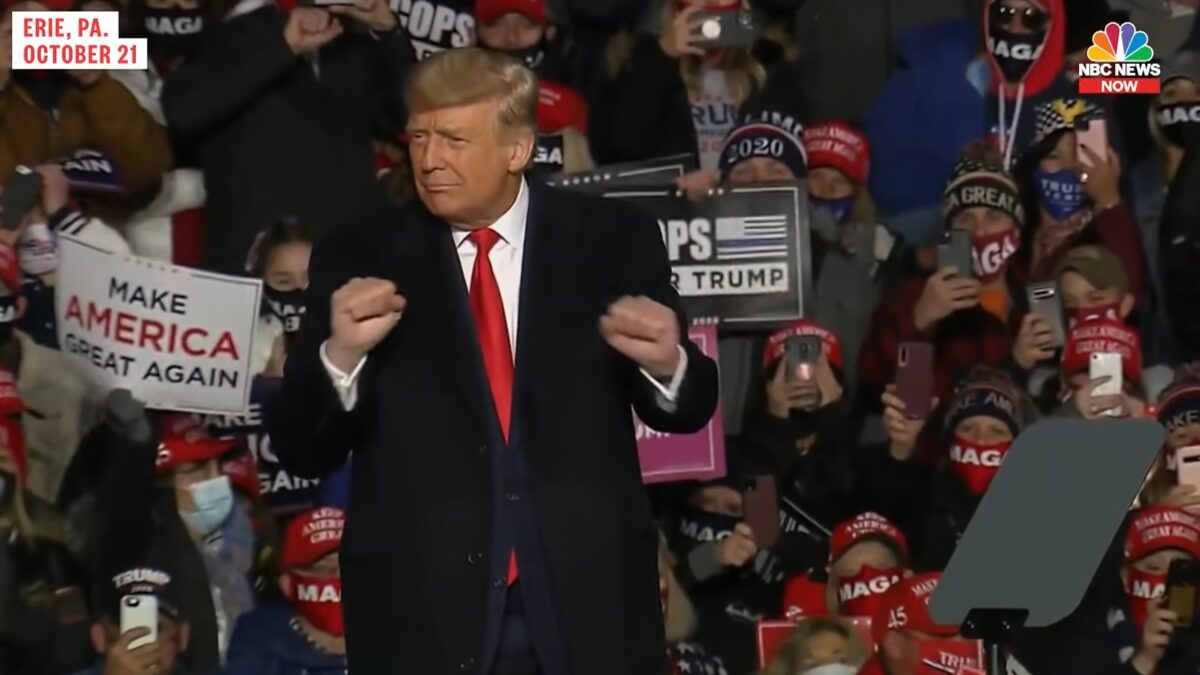

Editorials last month include “The Problem of Gerontocracy,” “The Case for Age Limits in American Politics,” and “Is the US Stuck in a Gerontocracy? Half of Americans support an upper age limit on political service, according to a 2022 survey. Although Jack Butler writes that the older generation should serve as “transmitters for proper inheritances,” many 25-54 influencers and educators would like to show older Americans out the door from national affairs.

“The Case for Age Limits” appeared in Esquire, which seems also to be the most devoted media commentator, supporter, and cheerleader for the acting career of Jeff Bridges. Bridges is one actor who embraces typecasting. His 1998 role as “the Dude” in “The Big Lebowski” was his last until 2010, and to this day he leads a band called The Abiders, named after a famed “Lebowski” quote.

Juxtaposed against Walter Sobchak’s satirical caricature of masculinity, the Dude reinforced cosmopolitan Gen X and Millennials’ tendencies, and called these “pacifists.” A self-awareness to “abide” instead of getting swept up in manias such as Presidents Clinton and Bush’s foreign war drumbeats certainly has its value. In application, however, the Dude’s “pacifism” tends to engender nonchalance in national and personal outcomes, evasion of raising a family, and diminishment of self-defense, and other traditionally male priorities.

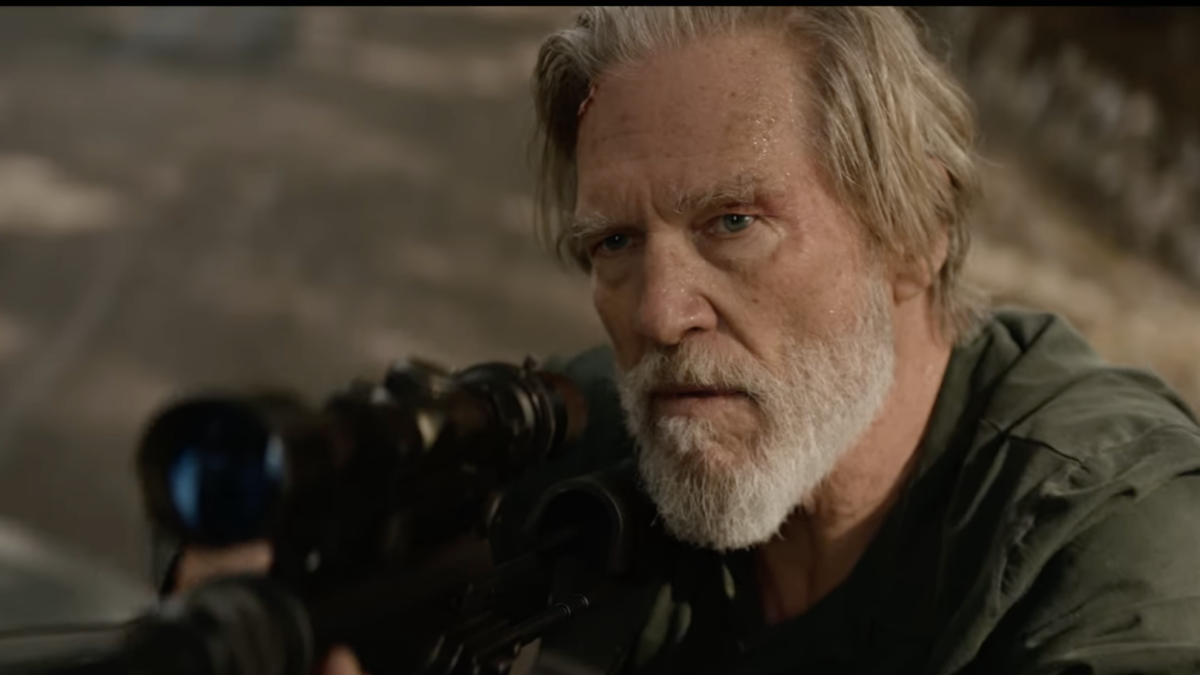

Whereas Joel and Ethan Coen’s “Lebowski” fostered a disinterest in proactive male indomitability a generation ago, Bridges’ latest work, “The Old Man,” which debuted on FX this summer, revives the appearance of powerful masculine themes. Unfortunately, it also lobotomizes them of meaning and relevance. What is left after “The Old Man’s” gutting of meaning is a carcass of “man” that retains supply lines of charisma, but stinks the longer you stand around.

Bridges stars as Dan Chase who is ever on the run, mentally when not physically, and an examination of the spy psyche. John Lithgow plays the foil, FBI Assistant Director Harold Harper, who worked closely with Chase in Cold War special ops five decades earlier. Their male bonding straddles superficiality and death-facing military brotherliness, and they share a cunning mentor.

What inheritances do these senior men transmit? In one interaction with seventh-floor FBI officials, Harper explains, “The game Chase and I played when we were young, I’m starting to realize, has no rules. The puzzles have no solutions. They just lead to other puzzles. That’s what makes it so interesting.” The government’s top authorities such as Harper, then, accept the futility of a goalless fight, while Harper encourages junior officers to get their interests caught up in geopolitical games anyhow.

The transmission devolves from futile to ghastly. During a flashback to covert action on the ground in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion, young Dan Chase says the Afghan theater is his favorite because it provides his best chance to “kill Russians.” Noting the moral monstrosity this line represents, Chase’s unique role in that country is code-named “Hamzad’s Monster.”

In real history, an American fighter against Soviet positions would have been more likely to say, “kill commies.” We are not ethno-murderers, and many of our warriors abide by meaningful moral convictions that include beliefs in religious, economic, political, and health freedom, not anti-Russian bloodthirst. Stripping Chase of conviction while he fights the Soviets lowers him to hatred of the people of a country, a largely Christian one.

Despite its ideological vapidness, “The Old Man” delivers more introspection than many out-of-retirement action dramas like “Top Gun: Maverick,” “The Rock,” “The Expendables,” and even “Balboa” and “Creed.” Chase, Agent Adams, Hamzad, and others’ inner experiences include pounding nightmares and visitations from the deceased. The words “country” and “family” are uttered regularly as the characters express their haunting thoughts.

Amid this, however, there is never a reference to God. A remembrance or talk with God would have fit in cinematographically. Yet despite the actual majority of faithfulness in the nation’s services, and for all the personal experiences “The Old Man” conveys, its servicemen skip out on prayer life. The classic motto, “God, family, and country,” is abridged to its latter two — what could go wrong?

Season one is brilliantly written (loosely based on the novel) and distinctively acted, but man’s role in patriotically defending liberty has its soul sucked out, and his protectiveness toward family becomes distorted, turning “The Old Man” into a nihilistic wasteland in the clothing of a soldier’s thriller.

Upon this flattened terrain rides not man’s deeper senses of purpose, but old men’s fever dreams. The set of solid facts known about Chase’s life erodes, dizzyingly, with each plot turn. The annihilation of the lead’s conviction, in turn, reduces Chase’s deceased wife, Abbey (Leem Lubany), who appears in memories, and Zoe (Amy Brenneman) to chronic disorientation.

If lobotomized rudderlessness informs the government’s moves from one unsolvable puzzle to the next, then there is only an illusion of a republic. Officials in “The Old Man” wax purposeless and vain, not for the reasons in Ecclesiastes 1:1 that “all is vanity,” that is, to highlight the desperate imperative of knowing God to help the nation reach its destiny, but because the state’s directorship finds meaninglessness “interesting.”

Drama critical of foreign entanglements and unconstitutional violations of citizens’ privacy is one thing. Transforming elder leaders into levers and pawns who lack a hint about what they stand for, are manipulated by foreign adversaries, and at times cease to exist to their own families is another, smacking of a produced agenda.

“The Old Man’s” twisty, yet ultimately vacant, psychodrama and explosive action can be briefly enjoyed while remembering it is a Hollywood producer’s show, not a patriot’s.