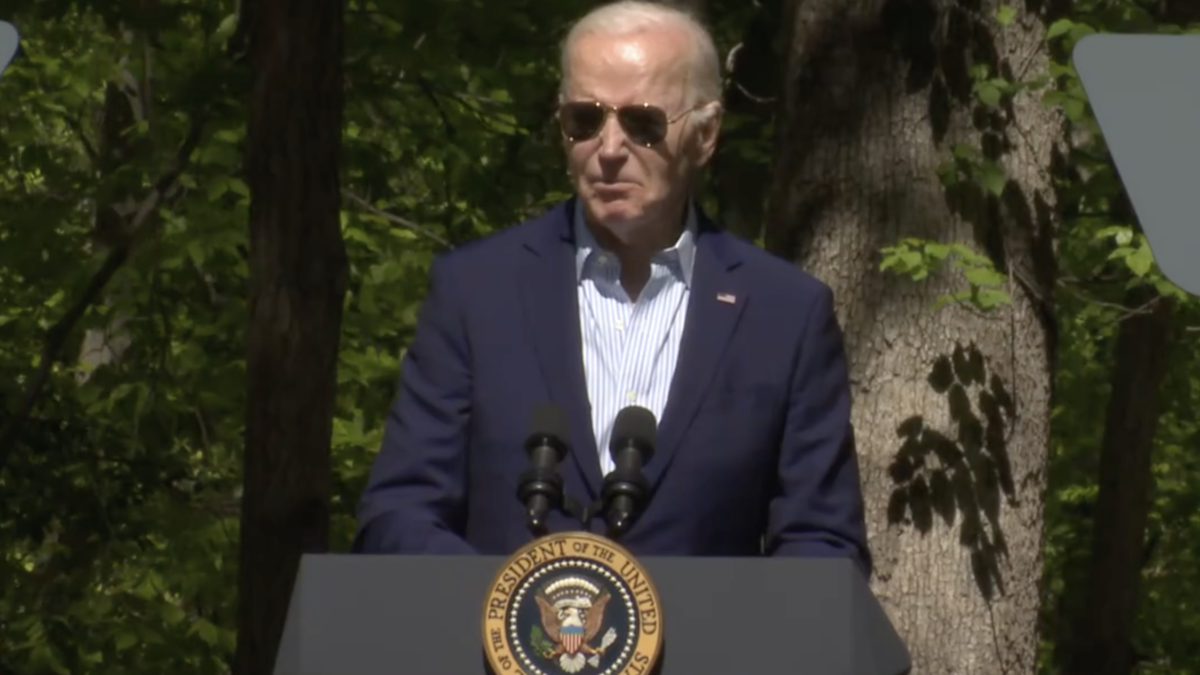

President Joe Biden continued to follow through on his campaign pledge to enact leftist environmentalism this month when he suspended oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR).

The decision was cheered by leftist environmental groups as a victory for wildlife and social justice, supposedly protecting indigenous tribes from the alleged devastation of oil and gas drilling hundreds of miles from their homes. Biden Climate Adviser Gina McCarthy celebrated the move as “an important step forward fulfilling President Biden’s promise to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.”

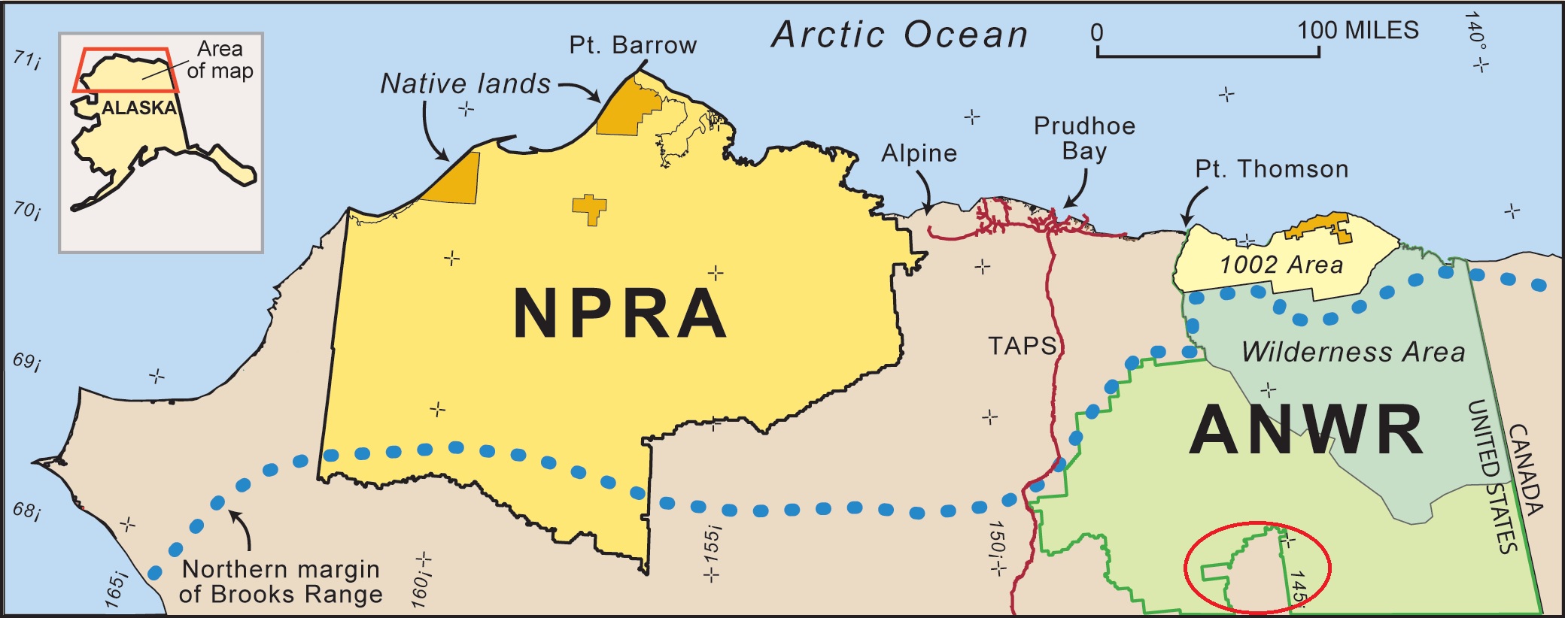

The Trump administration had opened the door to drill on the Refuges’ coastal plain, a nearly 1.6 million-acre stretch on Alaska’s north coast. The 1.6 million-acre patch along the north slope is less than 10 percent of the total refuge that stretches 19.6 million acres across northeast Alaska, a total about the size of South Carolina.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that below the surface of the north slope’s 1.6 million acres temporarily opened for leasing, known as the 1002 Area, lie between 4.3 and 11.8 billion barrels of recoverable oil. If opened for operations, it could become the most productive oil field in the country at a time gas prices are soaring to seven-year highs under the new administration.

Yet on June 1, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland signed an order to bring leases to a halt, claiming “inadequate study” of the drilling’s impact by the prior administration. “The Secretary shall review the program and, as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, conduct a new, comprehensive analysis of the potential environmental impacts of the oil and gas program,” the order reads.

The Gwich’in Tribe, who live south of the massive wildlife refuge, claimed Biden’s decision to reverse course was a win for their “tribal sovereignty” by protecting the primary caribou herd in the region, a key regional food source.

“The Gwich’in Nation is grateful and heartened by the news that the Biden administration has acted again on its commitment to protecting sacred lands and the Gwich’in way of life,” said Gwich’in Steering Committee Executive Director Bernadette Demientieff on the heels of Haaland’s order. “After fighting so hard to protect these lands and the Porcupine caribou herd, trusting the guidance of our ancestors and elders, and the allyship of people around the world, we can now look for further action by the administration and to Congress to repeal the leasing program.”

The Gwich’in have played a prominent role in keeping ANWR free of development, partnering with leftist groups to keep these millions of acres of U.S. land unused indefinitely. Writing in The Hill, Finis Dunaway, a history professor at Trent University and author of “Defending the Arctic Refuge,” summed up the Gwich’in’s more than four-decade crusade to ensure the absence of development on one of the nation’s last known major reserves of oil and natural gas.

The Gwich’in Steering Committee — founded by Gwich’in from Alaska and Canada in 1988 — reframed public perceptions of the refuge, helping grassroots audiences to see the Arctic coastal plain as vital to Indigenous food security and cultural survival. Their leadership and advocacy widened support for protection of the refuge, encouraging religious and faith organization, humans rights groups and many others to fight for Indigenous rights and environmental justice. These unlikely alliances fostered grassroots involvement that proved critical to the numerous close calls and impossibly narrow victories that followed.

In other words, the Gwich’in have been fundamental to preventing of any sort of development on the nearly 20 million acres of pristine wilderness in the name of “environmental justice” since 1988. Yet only four years earlier, that the same tribe, which in fact lives outside the refuge, tried to lease their own lands within the habitat of the Porcupine caribou for oil exploration.

Gwich’in Hypocrisy

In the early 1980s, the Gwich’in tribe sought to lease the last inch of every acre it owned in the Alaskan Venetie Reserve to oil companies seeking to drill for potentially lucrative reserves.

The letter below dated April 1984 shows the tribe authorizing oil leases on the Venetie Indian Reservation, located just outside ANWR boundaries, 400 miles south of the area on Alaska’s north slope where developers have more recently sought to drill.

“The Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government hereby gives formal notice of intention to offer lands for competitive oil and gas sales,” the letter reads. “This request for proposals involves any or all of the lands and waters of the Venetie Indian Reservation… Bidders awarded leases at this sale will acquire the right to explore for, develop and produce the oil and gas that may be discovered within the leased area.”

According to a 1991 article in the Christian Science Monitor, however, Exxon’s exploration came up short in finding any lucrative reserves under the surface of Gwich’in land.

“Much to the dismay of the villagers, I was the poor guy who had to go around and tell them we weren’t going to drill a well,” Stuart Gustafson, an exploration representative, told the paper at the time.

By 1985, the tribe had changed their tune on Alaskan drilling, and had become vehemently opposed to oil and gas exploration at all costs after their own lands turned up no profitable deposits. By the end of the decade, as Dunaway outlined, the tribe had teamed with leftist environmental groups to prohibit drilling in ANWR just to the north.

The ensuing decades-long struggle is yet another clear-cut illustration in what’s become routine among leftists: the left finds a group they declare “oppressed,” then amplify and exploit their alleged grievances for political objectives.

The Caribou Are Fine

At the heart of Gwich’in objections to drilling in ANWR are claims development could decimate the coastal plain’s caribou herd area that tribes rely on, including the Gwich’in and the Iñupiat. The Iñupiat are the only Alaskan tribe with communities residing entirely in the refuge, and they have lobbied in favor of oil and gas extraction in conflict with the Gwich’in for years.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an estimated 219,000 caribou between the Porcupine Herd and the Central Arctic Herd migrate in and around ANWR and provide sustenance for the local tribes. The FWS map of the herd territory is below.

Oil and gas production in Prudhoe Bay has shown no adverse effects on the Central Arctic Herd in the area. In fact, the herd’s numbers have continued to rise and fall within its natural cycle, reaching 70,000 in 2010, according to FWS, and back to 22,000 in 2016. The caribou in the region were estimated at fewer than 20,000 in 1997. Drilling operations were active at Prudhoe Bay for decades prior.

The map below from ANWR.org, edited to include a red oval where the Venetie village is located, shows the bay’s proximity to ANWR, just 60 miles west, located squarely within where the Central Arctic Herd calls home.

The Gwich’in-offered leases offered scant provisions for the protection of the caribou shared by the Iñupiat tribe hundreds of miles north. According to the Christian Science Monitor, leases with the Venetie Gwich’in offered “two sentences dealing with the animals’ welfare in the 20-page lease agreement signed.”

Gwich’in Infringement On Tribal Sovereignty

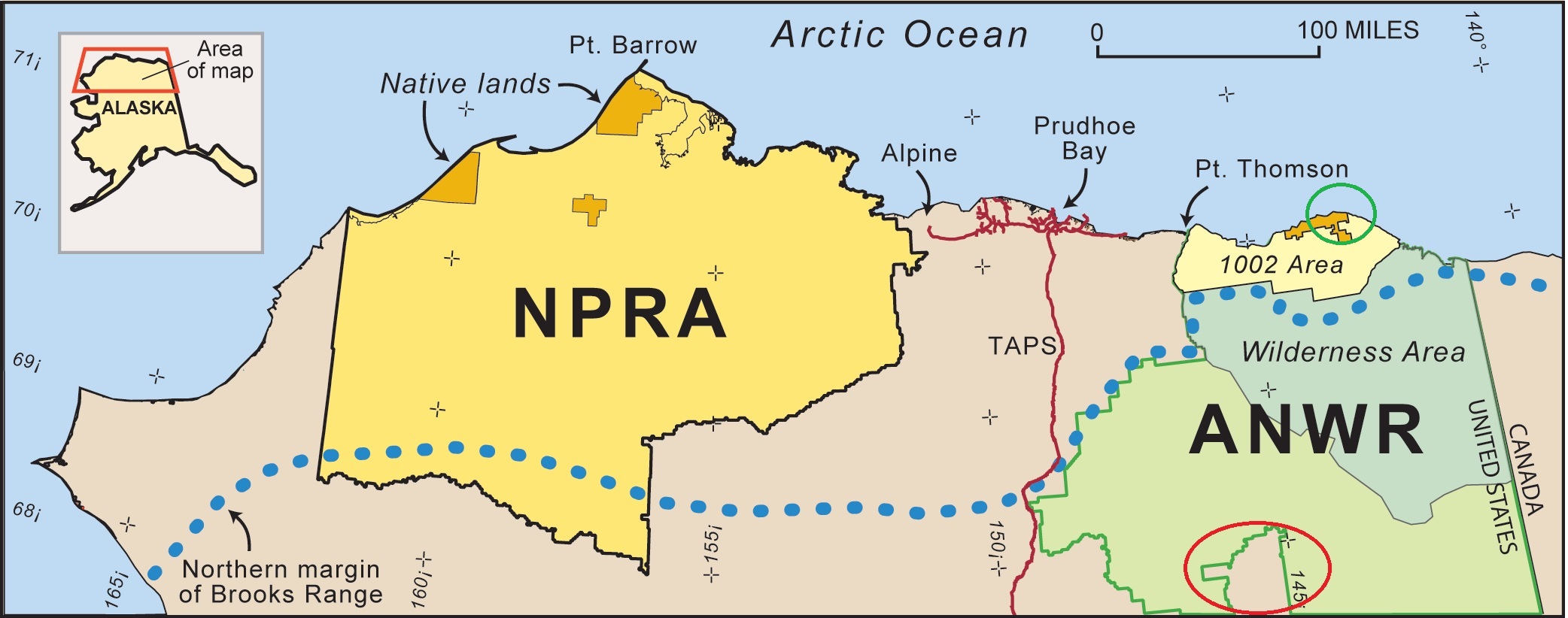

The Gwich’in claim drilling hundreds of miles north of where they live is an infringement on their way of life. Yet the Iñupiat tribe is the only tribal nation with land claims within the nearly 20 million-acre ANWR itself, let alone inside the 1.6 million-acre stretch where drilling has been proposed.

The Iñupiat locate home on Kaktovik Island, otherwise known as “Barter Island” for its trade significance in the early days of European exploration and migration. The island resides in the 1002 area in the map shown again below, also edited to highlight its location with a green oval east of Pt. Thompson. The red oval again shows where the Gwich’in reside, far outside of the refuge in which the tribe demands no development. The dotted blue line represents an entire mountain range between the two Indian nations.

The Iñupiat has fought a losing battle for years to lease its own lands for oil and gas exploration, only to be hampered by the Gwich’in tribe’s campaign allied with big-megaphoned progressive environmentalists. The Gwich’in went as far as the submit testimony to allege human rights abuses at the United Nations (UN) last year.

“The fact the Gwich’in Steering Committee finds itself speaking at the U.N., in corporate boardrooms and other high-profile locations is only due to the fact they’ve been co-opted by ENGOs and eco-ideologues to portray victims in a narrative of fear,” Rick Whitbeck, the Alaska state director for the non-profit energy group Power the Future, told The Federalist.

To reclaim their voice, representatives of the Iñupiat have testified before Congress to advocate opening the refuge for drilling and have sent letters to Capitol Hill demanding it reclaim the rights to issue leases. In 2019, the Iñupiat tribe sent a letter to California Democrat Jared Huffman, who has repeatedly introduced legislation to keep the refuge off-limits to development at the Gwich’in’s behest.

“The views of the Iñupiat who call ANWR home are frequently ignored, and your bill reinforces the perception that the wishes of people who live in and around the Coastal Plain are less important than those who live hundreds and thousands of miles away,” the tribe wrote.

Still, Huffman has remained one of Washington’s staunchest opponents to drilling in ANWR, reintroducing legislation again in February to permanently ban the region from oil and gas development, citing Gwich’in concerns.

“The Gwich’in Nation, living in Alaska and Canada and 9,000 strong, make their home on or near the migratory route of the Porcupine caribou herd,” Huffman wrote, “and have depended on this herd for their subsistence and culture for thousands of years.”

So too have the Iñupiat, however, and their wishes to lease their tribal lands for drilling have been hampered by a rival tribe partnered with leftist interests for political purposes.